By Janet Philp

Fantasy tales are littered with beings that can fly, whether in video games like The Legend of Zelda1 and Skyrim2, classic films such as Prince Vultan’s hawk men in Flash Gordon3, dozens of Marvel and DC heroes, TV series, blockbusters like the Harry Potter4 series and the classic Dungeons and Dragons5. The fantasy creatures of China Mieville provide us with a multitude of winged and armed creatures whilst Le Guin provides us with winged entities of a more recognisable feline form (Le Guin, 1999).

Characters who can fly capture our imagination. They are seen as having the ability to rise above and they often have power and God-like appearances. In this article we will be looking at the anatomy of flight and whether it can help us understand how these beings can fly, or whether it is best left to special effects.

As we are looking at self-propelled flight, we will ignore characters who fly by some means of alternative propulsion such as Ironman6, Thor7 and Mary Poppins8. We shall ignore those that fly using a cape such as Dr Strange9 and potentially Superman10 and we will limit our exploration to those creatures who present with anatomical wings that propel flight as opposed to fins or flaps that allow for gliding.

In the history of life on Earth there have only been four classes of creatures who have possessed the ability to truly fly. These are the pterosaurs, insects, birds, and bats.

Pterosaurs have been extinct for millions of years and so how they flew can only be speculated upon. Insects, due to their exoskeletons have a different anatomy and flight patterns which are not often represented in fantasy literature, although accurately depicted in the new Dune movie11. This article will concentrate on bats and birds and how they can inform our understanding (Evans 2020) of the flight of fantasy creatures.

Bats

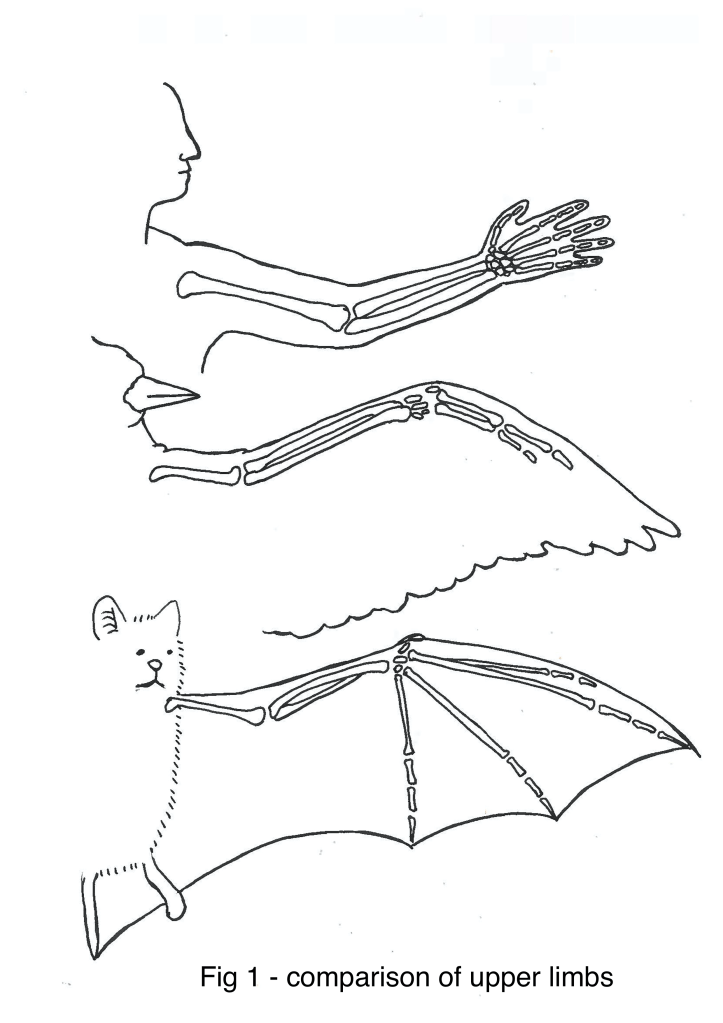

A bat’s forelimb follows the same basic pattern as any mammalian forelimb. This can be seen in Fig 1 – a comparison of the upper limb of man, bird, and bat. The bone nearest the body is a single long bone referred to as the humerus which has a comparable bone density to land mammals. The lower part of the limb consists of two thinner bones called the radius and ulna. There is then a collection of small bones that constitute a wrist and several extensions or phalanges that act as fingers or struts for the wing membrane. From the radius onwards these bones become increasingly less calcified resulting in the final extensions being very flexible (Swartz et al., 2012). The membrane that runs between the body and the wrist is essentially skin. This skin is highly organised with elastic fibres that can be contracted to stiffen the membrane (Tokita et al., 2012), a property mimicked to great effect by Lucius Fox in Batman Begins12. This means the wing structure can be very rigid on the power stroke, usually the down stroke, and very flexible on the return stroke.

Hermanson’s analysis of the bat musculature (Hermanson, 1998) identifies the muscles used in the downstroke as the pectoralis, the serratus ventralis (would be serratus anterior in humans) and the subscapularis. Those muscles used in the upstroke are the trapezius, the deltoids, the supraspinatus and the infraspinatus. These are the same muscles that a human would use if they extended their arms to the side and moved them forwards and backwards. This gives a bat a very similar appearance to a mouse that has hit the gym to work on his shoulders (and missed leg day).

There is a requirement for structural support for a flapping wing and the bat achieves this by having elongated collar bones, or clavicles. These hold the top edge of the shoulder blades, or scapula, away from the body creating a scaffold onto which the wings can attach. Bats also have a unique muscle, the occipito-pollicalis which originates at the occipital region (rear) of the head and enters the front edge of the wing. These structures provide the wing with a firm leading edge which is important in flight (Norberg, 1969).

The ratio of the weight of the subject to the wing area is important in flight. It is even more critical in animal flight where the wing is constantly changing shape than it is in fixed-wing aircrafts, where most of the research on flight mechanics has been conducted. Consequently, there are few bats over 2kg in weight.

Flying is a very energy-expensive operation. At the point of take off a bat’s heart rate doubles and its respiration triples. To sustain this higher metabolic requirement the gastrointestinal tract has a very large surface area to ensure the maximum amount of nutrition is derived from food. The lungs and heart are larger than would be expected based on body size and the blood has an increased oxygen-carrying capacity.

In mammals there is a relationship between breathing and movement, something that dancers are keenly aware of (Dennis and David, 1983). This is even more accentuated in the bat where the muscles that provide locomotion are attached to the rib cage, the movement of which is imperative for breathing. It is perhaps because of both of these forces applying to the rib cage that a bat’s respiration is synchronised with its wingbeat (Suthers et al., 1972). This is an important factor that will limit the size of any flying creatures that utilise muscles attached to the rib cage.

Birds

Although birds’ wings follow the same bone structure as bats; one long single bone followed by a pair, followed by several extensions, the bones are more calcified. The structure is covered in firm feathers giving the wing much more rigidity. This places much greater force on the shoulder joint and so it is provided with more stability. This takes the form of two structures. The first is the furcula, the wishbone, formed by the fusing of the two clavicles. The second is the coracoid bone which fixes the scapula to the sternum (Fig 2). These structures give a stable base on which the bird can use its flight muscles to move the wing. Due to the fixed nature of the shoulder joint, the flight muscles would be ineffective if they attached to a flat sternum as found in humans and bats. To address this, birds have evolved a vertical keel bone onto which the flight muscles can attach.

The muscles on the breast of a bird look so large because birds have developed a unique system for flapping their wings which places all the muscles on the breast rather than splitting them in front and behind the shoulder joint like humans and bats (Taylor, 2020).

The muscle that pulls a bird’s wing down during flight is the pectoralis major, same muscle that moves your arm, and the muscle sits in the same place, between the sternum and the shoulder joint. The muscle that pulls the wing up is the supracoracoideus. This is a much smaller muscle that sits underneath the pectoralis major (Fig 2). It can be smaller because birds have developed two effective recoil systems. The first is the furcula. As the wings move down the two ends of this bone move apart, as they spring back towards each other the wing raises (Jenkins et al., 1988). The supracoracoideus also has a very strong tendon which attaches to the back of a humerus via a unique pulley system in the shoulder joint area.

The largest birds that fly can be 18kg (Californian Condor, Gymnogyps californianus) to 21kg (Great bustard, Otis tarda) although continuous flapping does not occur in birds over 4kg (Rayner, 1981).

Birds do not rely on their rib cage movement for breathing. Although birds do have lungs, they also have a system of air sacs that provide a continuous unidirectional flow of air around their bodies. This system occupies around 1/5th of their bodies, whereas the respiration system of a human only occupies around 1/20th. The bird’s capillary blood volume is 2.5-3 times greater than that found in the equivalent-sized land mammals providing them with the energy needed to fly.

It can be appreciated that both bats and birds have several physiological changes that provide them with the energy necessary to sustain flight but there is still a restriction on maximum size. It’s possible to imagine that a wyvern (a dragon with hind legs and wings) might exist as a larger version of a bat. This is how such creatures are depicted in Game of Thrones13, Reign of Fire14, Skyrim2, and in some of the species in Harry Potter4. Anatomically such a creature could fly although they are more likely to be the size of the sparklings in A Natural History of Dragons (Brennan, 2014) (butterfly sized). The physics of wingspan versus weight would render anything large enough to be ridden by a human-sized creature earthbound.

Wingspan and generating lift are issues with physics. The maths is complicated – a recent podcast tried to explain it in an accessible way (Clark, 2018). But here is a much more pressing matter that needs to be addressed. It’s the anatomy! There has never been a creature that has possessed four limbs and functioning wings and yet this is often presented in fantasy literature. Whether in classical depictions of an angel or demon, numerous dragons, and other creatures such as thestrals and hippogriffs from Harry Potter4 or even in the flying monkeys of the wizard of Oz15 creatures with four limbs and wings are commonplace in fiction and unprecedented in nature.

Before we analyse humanoid flight, we should appreciate that wings were possibly never intended to suggest flight. To most people the classical winged humanoid is the angel, and its nemesis, the demon – a fallen angel where the wings have transformed from feather to membrane presumably based on the heat of hell. The difference is best explained by C.S. Lewis:

Devils are depicted with bat’s wings and good angels with bird’s wings not because anyone holds that moral deterioration would be likely to turn feathers into membrane, but because most men like birds better than bats. (Lewis, 1942)

Whilst Lewis refers to the Christian symbolic angel, such winged creatures appear in a number of religions and indigenous mythologies. Within early Judeo-Christian religious texts, the appearance of wings was not often mentioned with descriptions of bright lights depicting that the humanoid was something more significant. Martin (Martin, 2001) suggests wings were introduced for a specific reason; the wings were introduced as a symbol that these people were set apart, a different social standing, a theory that has already been covered in previous articles, but would it be possible to have winged humans who could fly?

It’s hard to see how – there are several things to consider.

Movement – Although birds are bipedal, their spine is still uppermost whereas a human’s spine is towards the back of the body. This would turn the required motion through 90 degrees; for flight, the human would need to flap their wings up and down in relation to their body whereas bats and birds flap their wings forwards and back in relation to their body.

Wingspan – For both birds and bats the longest part of the wing is from the ‘elbow’ to the tip. In the average human this could not exceed 6 foot, otherwise the wings would drag along the ground when folded, and so the wingspan is fixed at somewhere around 18 foot – 6 foot, twice folded. Applying the maths, the wingspan of a 90kg human would be 20 foot so it is within the realm of mathematical possibility.

Wing Placement– Creatures with four limbs and wings are usually depicted with their wings attached to the scapula. This can be seen in films like Dogma16 where the first bone of the wing arises from the scapula area. This creates the issue that the movement of the arm and wing are joined. From an osteological point of view, it is possible to see that if the arm remains stationary then the wing could function but any arm movement of greater than 60 degrees involves movement of the scapula. This would mean the wing structure would move as the arm was used making it unwieldy to reach anything above head height, although this might not be a problem if you could fly.

The scapula in the bird is a much-reduced structure as it does not require the attachment of large back muscles to control the limb. The introduction of a second scapula limb joint above the forelimb is a possibility. In The Resurrectionist (Hudspeth, 2013) there is the suggestion of the wings being positioned in the shoulder blade area but with alternative support. Bony structures arise from the sternum giving a structure rather like an American football shoulder padding onto which the wings could attach.

The other possibility is to fix the wing below the forelimb directly to the spine. This would require a joint between 1 or 2 vertebrae and the wing bone in a similar fashion to the joint of the ribs. If the joint spanned more than 1 or 2 vertebrae it would affect spine mobility. Whilst it’s possible to imagine such a joint functioning in something the size of a dragon it is more of a challenge to imagine a functioning wing on a humanoid where the bone is only as thick as a rib.

All these options offer challenges with the required musculature.

Musculature

Each of the suggestions above offers different anatomical challenges.

For a wing attached to the scapula – We have seen that some muscles, such as the pectoralis major are common in arm and wing movement. If arms and wings are both present, then extra muscles would be needed. In some fantasy texts (Hudspeth, 2013) the pectoralis thoracis has been invented to allow these two separate movements. Muscles that reach the wings on the back of the body by overlapping the muscles that the forelimb would need to function pose a challenge. Whilst the human body has many sets of overlapping muscles, they generally perform very similar functions – the muscles that overlay each other in the front and the back of the thigh are all involved with leg movement. For two muscles to overlay each other where one set must be kept stationary whilst the other contracts would be unusual. In a similar fashion to the bone placement above, it may be possible to imagine the arm being kept still whilst the wing flaps but to imagine the superficial muscle that activates the wing remaining stationary whilst the pectoralis major underneath it moves the arm is hard. The arm would be rendered almost useless.

Second scapula above the forelimb scapula – it was mentioned above that it would be possible to create two bone structures that protruded from the sternum and pass over the shoulder towards the back of the body. If wings were attached to these then how could they be moved?

In the human body the scapula acts as an attachment point for 17 different muscles. Very few muscles concerned with forelimb movement connect directly to the rib cage because it is constantly moving and therefore makes a poor anchor. The movement of the ribcage is integral to breathing and therefore any muscles that attach to the rib cage would probably need to work in a similar fashion to the bats; synchronised to the breathing. There are two options for moving this wing structure: the avian option of two muscles at the front or the mammalian option of a set of muscles at the front with a matched set of muscles on the back. There are three obvious problems with this suggestion.

Firstly, to operate a wing that is large enough to lift a humanoid the muscles on the front of the body would need to be quite large. If you reach your hand to your mouth and look down at your chest you will see that there is not much space available for an extra muscle.

Any extra layer of muscle would result in your hand being unable to reach your face. The muscle would also need to be quite narrow as if it fixed to the wing further out than the shoulder joint it would impede the use of the arm.

It is doubtful whether a muscle attached to a normal human sternum would be large enough and so an extended sternum, like a bird’s, would be required ensuring that the arms lose their functionality. The sternum in a human terminates around the level of the 5th rib. This is a short attachment for the size of the muscle that would be required but to extend the sternum would affect the flexibility of the human torso.

Secondly, there are a lot of structures within the human neck which do not withstand compression i.e. the airway and blood supply to the head. Although the trachea has cartilaginous rings to maintain an airway, large muscles contracting either side of the structure would be akin to a UFC choke hold and result in an inability to look anywhere other than straight ahead whilst flying or risk unconsciousness.

Thirdly, this musculature would result in wing movement that is anteroposterior (forward and back). To produce lift, the humanoid would need to bend at the waist or have an elaborate musculature within the wing to rotate the joints, adding to the weight and the bulk.

Attachment below the forelimb – To facilitate retaining a functional forelimb, the remaining option is to drop wing attachment down to below the forelimb. In the humanoid this option would still require the large flight muscles to attach to the front of the body where there is no supporting structure. The muscle bulk would create bulges that would create a very different body shape. Any compression above the waist would still restrict breathing, compressing the floating ribs at the bottom of the rib cage, which are prone to breaking.

Conclusion

There does not appear to be a possible option for the attachment of wings for humanoids. All the proposals above would produce a creature who bore very little resemblance to the creatures we see in fantasy films, rather a panting parody of a human with arms that would be as useful as a T-Rex’s.

Many of the arguments for humanoid flight are reflected in the quadrupeds. To attach to the scapula produces a wing that would move with the forelimb. This is not of such a hindrance although we would need to ignore the movements of Pegasus and Buckbeak where they gallop through the air as they fly, as such movement would present a challenge to maintaining a smooth flight path.

As the forelimb of a quadruped is almost at a right angle to the chest, as opposed to the human configuration, it offers more options for musculature attachment.

In The Resurrectionist, Hudspeth (Hudspeth, 2013) chooses to locate the wings of the Sphinx and Pegasus on the scapula with overlapping musculature which would cause limb and wing to move together. His depiction of a dragon is of the wingless oriental variety and so he offers us no clues for the most famous of winged quadrupeds.

Dragons

On the front cover of A Natural History of Dragons (Brennan, 2014) there is a tantalising glimpse at a possible solution. In a partial dissection of a dragon, it shows a joint attaching the wing behind the shoulder joint. Two muscles wrap around the dragon’s torso and insert on what would be the sternum of the dragon. This design by Todd Lockwood (Lockwood, 2009) offers a solution whereby the forelimbs function as those of a quadruped but the wings are positioned behind the scapula and powered by the inventively named anterior pectoralis major draconis and posterior pectoralis enigmatus draconis. The presence of large deltoid and latissimus dorsi muscles indicate a model of flight based more on bat anatomy rather than bird, although an accompanying skeletal diagram is yet to be drawn revealing whether the artist was thinking whether a furcula and keel-shaped sternum would be present and how the wing articulates with the skeleton. The large muscle groups would affect the function of the rib cage but clearly, there are other anatomical issues with dragon’s breath (Knoepfler and Knoepfler, 2019), not least of all fire. The explanation of how wings may function for dragons holds for any quadruped and may also explain the wings of Le Guin’s feline forms, although the suggested names of the muscles may need to be addressed.

Whilst it is an interesting intellectual exercise to explore the anatomical possibilities of flight, it would not be fantasy literature if it obeyed all the laws of physics and anatomy as we understand them. Maybe there are forces we do not comprehend that assist the flight of creatures we do not normally encounter or maybe, like Rincewind in the Discworld, we should leave it all to our imagination (Pratchett, 1983).

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge conversations with my fellow anatomists who have inspired and reviewed this article.

BRENNAN, M. 2014. A Natural History of Dragons, UK, Titan Publishing.

CLARK, S. 2018. The physics and biology of flying mythical beasts. You Tube.

DENNIS, M. B. & DAVID, R. C. 1983. Running and Breathing in Mammals. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science), 219, 251-256.

EVANS, A. 2020. Wing swing, not shape, is key to bird flight. Journal of experimental biology, 223, jeb211441.

HERMANSON, J. W. 1998. Chiropteran muscle biology: a perspective from molecules to function. Bat Biology and Conservation. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution press.

HUDSPETH, E. 2013. The Resurrectionist, USA, Quirk Books.

JENKINS, F. A., DIAL, K. P. & GOSLOW, G. E. 1988. A cineradiographic analysis of bird flight: the wishbone in starlings is a spring. Science 241, 1495-1498.

KNOEPFLER, P. & KNOEPFLER, J. 2019. How to build a dragon or die trying, UK, World Scientific Publishing.

LE GUIN, U. K. 1999. Catwings, Puffin.

LEWIS, C. S. 1942. The Screwtape Letters, UK, Harper Collins.

LOCKWOOD, T. 2009. Musculature of the greater dragon [Online]. www.toddlockwood.com/dragons#/musculature-of-the-greater-dragon. [Accessed 6th September 2021].

MARTIN, T. 2001. The development of winged angels in early christian art. History of Art, 14, 11-29.

NORBERG, U. M. 1969. An arrangement giving a stiff leading edge to the hand wing in bats. Journal of Mammalogy, 50, 766-770.

PRATCHETT, T. 1983. The colour of magic, Colin Smythe.

RAYNER, J. M. V. Flight adaptations in vertebrates. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London, 1981. 137-172.

SUTHERS, R. A., THOMAS, S. P. & SUTEHRS, B. J. 1972. Respiration, wing-beat and ultrasonic pulse emission in an echo-locating bat. Journal of Experimental Biology, 56, 37-48.

SWARTZ, S. M., IRIARTE DIAZ, J., RISKIN, D., K. & BREUER, K. S. 2012. A bird? A plane? No, it’s a bat: an introduction to the biomechanics of bat flight. In: GUNNELL, G. F. & SIMMONS, N. B. (eds.) Evolutionary History of Bats: Fossils, Molecules and Morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

TAYLOR, M. 2020. How birds work, Uni Press Books Ltd.

TOKITA, M., ABE, T. & SUZUKI, K. 2012. The developmental basis of bat wing muscles. Nature Communications, 3.

Films

1 – The Legend of Zelda. 1986. Nintendo.

2 – Skyrim. 2011. Bethesda Software.

3 – Flash Gordon. 1980. Columbia EMI Warner.

4 – Harry Potter. 2001-2011. Warner Bros.

5 – Dungeons and Dragons. 1974-1997 TSR, 1997-present Wizards of the Coast. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson

6 – Ironman. 2008. Paramount.

7 – Thor. 2011. Paramount.

8 – Mary Poppins. 1964. Walt Disney.

9 – Dr Strange. 2016. Walt Disney Studios.

10 – Superman. 1978. Warner Bros.

11 – Dune. 2021. Legendary Pictures.

12 – Batman Begins. 2005. Warner Bros.

13 – Game of Thrones. 2011. Warner Bros. Television Distribution.

14 – Reign of Fire. 2002. Touchstone Pictures.

15 – Wizard of OZ. 1939. Metro Goldwyn Mayer.

16 – Dogma. 1999. Lions Gate Films.

Great article! I recommend SF novel “When We Have Wings” by Claire Corbett to you all. Problems sorted with a bit of handwavium but mostly with convincing cunning :)