By Phoenix Alexander

The organism is relentless

Calorie demanding, perpetually in need of hydration, oxygen, and a cocktail of other vitamins and minerals, requiring 4-8 hours sleep a night to repair itself from the ravages of the day, day after day. A lifetime’s worth of consumption.

This unkind—some might say anti humanist—characterization is famously articulated by the nefarious Agent Smith in The Matrix, where he attempts to psychologically break a human rebel leader, Morpheus, by telling him:

Every mammal on this planet instinctively develops a natural equilibrium with the surrounding environment, but you humans do not. You move to an area and you multiply and multiply until every natural resource is consumed and the only way you can survive is to spread to another area. There is another organism on this planet that follows the same pattern. Do you know what it is? A virus. (The Wachowskis, 1999)

The accusation, while effective for cinema, is not quite true. Smith implies that this “consumption” is a species-specific act, and not one located within a complex and interrelated ecosystem of both human and non-human life. If anything, plants should be the focus of his anger: they are the enablers of this “surviving,” this “spreading,” being masterful spreaders and survivors themselves. More radically: even drawing the lines between species may be a spurious rhetorical move. “A leaf is the only thing in our known world that can manufacture sugar out of materials—light and air—that have never been alive,” Zoë Schlanger reminds us in her recent book The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth (Schlanger, 2024). “All the rest of us are secondary users, recycling the stuff the plant has made… Think about it: every animal organ was built with sugar from plants” (Schlanger, 2024, pp. 27-28). Her (admittedly simplified) description is useful in exculpating the human organism specifically from the charge of excessive consumption. It is not our fault; we are enabled, built literally by component organisms and their byproducts, both visible and invisible.

Nevertheless, the human body and its source/s of sustenance tends to take on the nature of a problem to be solved in many science fictional narratives. From the replicators of Star Trek to the hideous ‘pigoons’ of Margaret Atwood’s Mad Addam series to the equally hideous ‘sligs’ of Frank Herbert’s Dune universe to the more mundane efforts of potato-growing in Andy Weir’s The Martian, authors and film-makers offer the gamut of appealing to radically unethical means of keeping the human organism alive in conditions that, even without the lack of food, threaten to kill it. (I am reminded here of the opening crawl to the movie Gravity: “Life in space is impossible”) (Alfonso Cuarón, 2013).

Of course, food does more than simply keep us alive. It is a living repository of history, culture, and ancestry; it is the passing on of skills down generations, a special sauce, a secret ingredient. One whiff of a particular dish makes time travelers of us, taking us back to our childhoods or other precious memories; the sight of a baker kneading bread can resurrect the dead, conjuring forth the image of our grandfather’s doing the same thing. Foodways (their ingredients, their technologies, and the cultural rituals around them) render tangible histories of colonialism, exploration, and hybridity. “Cuisines reveal and shape social relations and connect the past with present concerns and future possibilities” (Jane Dusselier, 2009).

So why is food so often a problem in science fiction? From a writer’s perspective, of course, you have to keep your characters alive. But what else? How does food and foodways contribute to the sketching of a wider fictional universe, and what can it say about economics, social organization, and planetary ecosystems?

Moving away from the unkindness of Agent Smith’s prognosis (and neatly sidestepping the current political issues of ageing populations and hysterical fears of falling birthrates, even as late capitalism, at least in the West, tightens its grip on the human organism, demanding more: consumption, waste, acquisition…) I turn to an unlikely source for a more hopeful solution to food production.

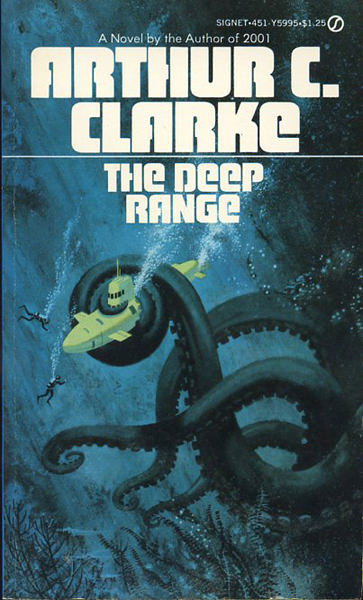

Arthur C. Clarke’s The Deep Range, published in 1957, relatively early in his career, is a poignant character study as well as an early example of ‘cli-fi’ and/or ecological utopia. The novel is set on a near-future Earth organized on a global scale—”a truly democratic government” whereby every person is able to cast their votes for policies electronically—with various ‘Bureaus’ handling different aspects of world affairs. Protagonist and former astronaut Walter Franklin suffers PTSD in the form of “astrophobia,” resulting in his never being able to go into space again. As the novel opens, Franklin and his friend Don Burley, both working for the Bureau of Whales, seek to uncover the cause of an increasing number of whale deaths: a huge problem, given that the animals yield a formidable amount of food products for the world’s populace. Alongside the whale products, Clarke also offers an alternative food source in the novel in the form of processed plankton, a plentiful and efficient source of protein: “the great plankton farms harvested their millions of tons of protein… [and humanity] would never be hungry again…” (Clarke, 314).

Arthur C. Clarke, The Deep Range (Signet: 1957)

If the problem of food scarcity is solved from the novel’s beginning—where, then, is there left for Clarke to go in the plot? Interestingly, he makes a moral-religious turn, emphasizing the spiritual and moral ‘health’ of homo sapiens as opposed to (merely) the generational continuation of the organism. This collective enlightenment is paralleled with the moving trajectory of Franklin’s own story. In one upsetting early sequence, the character attempts to kill himself by taking a submersible down into the depths of the ocean; upon being rescued, he reforges a new relationship with the ocean as a kind of rehabilitative space. Eventually becoming the Director of the Bureau of Whales, he is inspired by a Buddhist religious leader, Maha Thero, to abolish the fatal farming of whales entirely given their importance as “higher” (aka intelligent) animals (Clarke, 434). Recognizing the necessity for some killing of non-human life, Maha Thero makes the argument that given the state of technological progress, a kind of species maturation is ready to come about:

The production of all types of synthetic protein from purely vegetable sources is now an economic possibility—or it will be if the effort is made to activate it. Within a generation, we can shed the burden of guilt which… must at some time or other have haunted all thinking men as they look at the world of life which shares their planet (Clarke, 434).

The less spiritually-inclined Franklin interprets this lack of “guilt” as also readying mankind to present a best possible face to intelligent life beyond the planet: “man might someday come into contact with alien life forms that might judge him by his conduct towards the rest of the animal kingdom” (Clarke, 435). Again: the solving of the problem of global hunger brings with it physical and spiritual health to the species, in Clarke’s novel.

The contributors to this issue wrestle with similarly intertwined questions of food and/in science fiction. From religious practices and eating in space to the generation of such synthetic proteins; from zombie-killing video games as critiques of consumption to Daoist notions of immortality, the material and immaterial aspects of the human organism alike are considered. It is a feeling-forward and, in my opinion, a satisfying offering of utopian possibilities that sidestep the arguably too-neat utopia of Clarke’s vision in The Deep Range. Not only is his world fully democratic, as mentioned ( a democracy brought about through technological innovation), the global populace as rendered in the novel is described as rarely voting against their interests, excepting the odd particularly emotive issue. That such a populace may be concerned with presenting an image of philosophical decency, of unified, peaceful, and sophisticated planetary culture, to extraterrestrial life runs in startling reverse to Maggie Nelson’s bravura analysis of cruelty in her 2013 book in which she argues that making such a claim assumes that “shame, guilt, and even simple embarrassment are still operative principles” in American cultural life specifically, when the reality is that most people “are not ashamed, and they are not going to become so” (Maggie Nelson, The Art of Cruelty: a Reckoning, 2012, 32).

Maybe Nelson is right. Alternatively, maybe to extrapolate universal human truths from the sample group of one particular nation, at one particular time, is a bad idea. And yet, even if we are relentless, if we do insist on life—as surely we must, always—it must not be indiscriminately. Good eating, like good art, can emancipate us in ways we cannot even fully articulate but will, undoubtedly, recognize when it happens. “The door,” as Nelson insists, “has to stay open.”

Warmth and light,

Phoenix

§