By Lois Eastburn

From the holding cell was it possible to see beyond the end of the world and to imagine living and breathing again?

Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route[1]

It’s after the end of the world. Don’t you know that yet?

The Last Angel of History[2]

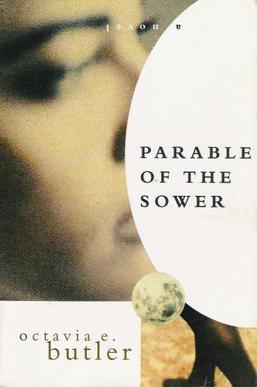

In science fiction writing, the future is both a territory for extraction and a site of resistance. Through what cultural theorists Kodwo Eshun and Mark Fisher have called ‘sf [science fiction] capital’, capitalism extracts value from futurity.[3] The financialisation of the economy is one way that sf capital colonises the future.[4] The hyper-commodities of the Star Wars franchise are another.[5] At the same time, the future of the planet — the future of the human species — is threatened by the rapacious extractivism that capital demands. Further, the futures of the peoples most subjugated and exploited under capitalism have always already been under threat. Kathryn Yusoff writes that the ‘Anthropocene might seem to offer a dystopic future that laments the end of the world, but imperialism and ongoing (settler) colonialisms have been ending worlds as long as they have been in existence’.[6] This dual vision — both proleptic and retrospective — is present in the novels Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998) by Octavia Butler and The Stone Gods (2007) by Jeanette Winterson. Both authors envision futures of the Anthopocene that are discursively (and recursively) engaged with colonial pasts, a conception of the future that finds it is, as Henriette Genkel argues in her anthology Futures and Fictions, ‘already implicated in the different dimensions of time’.[7] Both Butler and Winterson’s texts unsettle the narratives of empire and capital by orienting themselves in the alternative temporalities of speculative fiction.[8] They fiction futures to produce a ‘significant distortion of the present’, something that Samuel Delany considers a central technique of science fiction.[9] Their texts wonder at the possibility of other worlds and other futures, while grappling with the neoliberal fiction that such possibility is already foreclosed, that we are at the ‘end of history’.[10]

In science fiction writing, the future is both a territory for extraction and a site of resistance.

In John Akomfrah’s The Last Angel of History, his documentary-cum-science-fiction film about afrofuturism and the entanglements of ‘space, music, and the future’ in late-twentieth century black culture, the time-travelling narrator declares that the:

first touch with science fiction came when Africans began playing drums to cover distance. Water carried the sound of the drums, and sound covered the distance between the Old and the New World.[11]

Butler, who features in the film, writes from a similar position of awareness that, since the violence and displacement of the Middle Passage, science fiction has been a black technology of resistance, of establishing relationships with the ‘Old and the New World’, and of sense-making beyond the end of the world.

Continue reading “Old and New Worlds in Octavia Butler’s Parable Novels and Jeanette Winterson’s The Stone Gods“