By Marta F. Suarez

Dine or Die, with a Pinch of Comedy

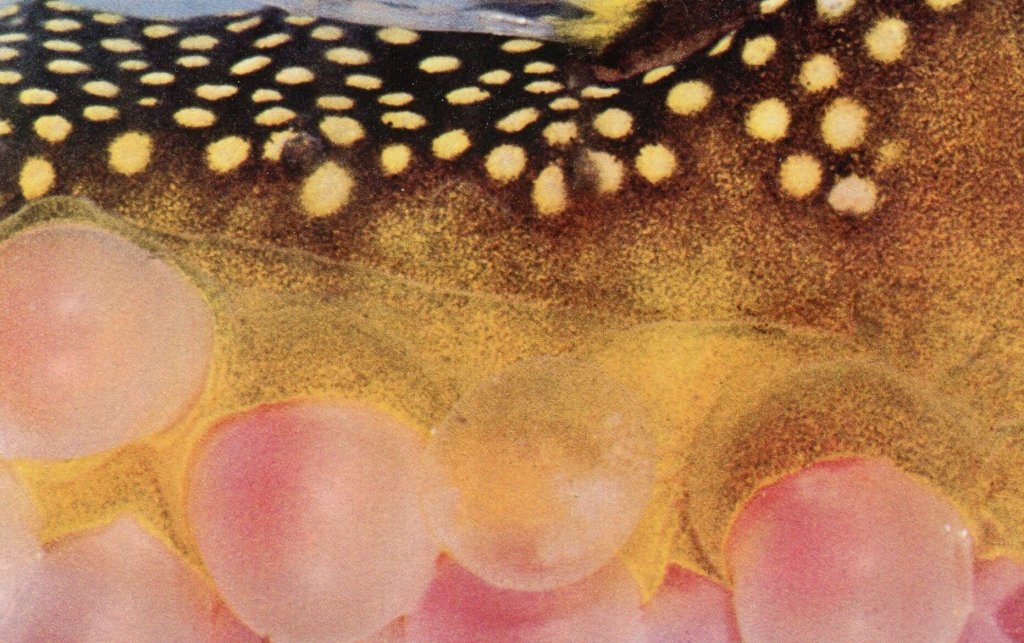

Delicious in Dungeon (2024, Netflix). Season 1, Episode 3. Living-Armour Stir Fry and Soup [00:18:57]

Delicious in Dungeon (Netflix, 2024-present) is Studio Trigger’s adaptation of Ryōko Kui’s eponymous manga (2014-2023). The series is set in a fantasy world that merges and echoes different fantasy and manga traditions popular in Japan. The overall setting takes the viewer to the dungeon crawl genre, which recently experienced a resurgence in the country after Etrian Odyssey Nexus (2018). The characters’ races and skills are shaped by influences of Dungeons and Dragons, the Middle-Earth world set by Tolkien, and even the Final Fantasy universe, which itself draws inspiration from these narrative traditions. However, what makes Delicious in Dungeon significantly different is the resonances of cooking series like Mister Ajikko (1986-1989), a manga series that had several sequel runs over the years, including a recent 2015-2019 one, titled Mister Ajikko Bakumatsu-hen. The first season comprises 24 episodes, with a new second season coming soon this 2025.

In the world of the story, adventuring parties enter dungeons looking for the legendary Golden Country, a kingdom transported by a sorcerer to the depths of an expansive dungeon, which is said to contain the ultimate treasures. Lured by wealth, fame, and adventure, different guilds enter this dungeon with the hope of finding the lost realm. One of these teams is led by Laios Touden, a tall-man (human) Paladin Knight who starts this quest alongside his sister Falin, a magic wielder; Marcille, a half-elf mage; and Chilchuck, a halfling thief. The opening scenes present the party’s encounter with a magnificent red dragon, against which they are losing. As the beast defeats them one by one, Falin uses her last strength before being ingested by the dragon to teleport the other members of the party out of the dungeon. Still alive but on the surface, the party is now several floors above where the battle took place and too far to attempt to rescue Falin. However, due to the magic of the dungeon, Falin could be resurrected if there are some remains and she has not been fully digested. With this in mind, the group decides to return, defeat the dragon and rescue any remaining parts of Falin. However, with time being of the essence, they realise that they cannot afford to stop to resupply and find provisions, as that would risk their chance to succeed. In a conventional dungeon crawl storytelling, the party would possibly open containers to find cheese and fruit, pick edible mushrooms and seeds, or perhaps kill a rodent and eat a left-behind spoiled pie in a moment of necessity. In contrast, Laios introduces the unconventional idea of eating the monsters they encounter, setting the course for the series. With this decision, the party ensures their survival and the journey becomes also one of gastronomic exploration.

Continue reading “Review: Delicious in Dungeon (2024)”