By Nick Wood

The sun darkened and the sky burned.

Sirens and smoke filled the air.

I stood in my family’s garden in Pinelands, Cape Town, watching the red horizon blaze and shift, as the neighbouring black townships of Athlone, Langa, and Nyanga were consumed by bullets, tear-gas, and flames. The Soweto Uprising had swept down from Jo’burg in 1976, from a nationwide youth protest opposing the teaching of Afrikaans in schools – which had been met with brutal police killings.

To me, then, as a young white teenage male, facing military conscription, it was as if the whole world could go up in flames.

Not known to me at the time, though, was that the destruction in Soweto included the burning down of the publishing house Africomic. Africomic was the home of South Africa’s first black comics superhero, Mighty Man.

The Mighty Man stories unravelled over seventeen issues, featuring the exploits of a policeman called Danny Ndhlomo, who was injected with a secret alien serum. The serum gave him superhuman strength and speed … and he became Mighty Man.

Superheroes often have secret identities. In the case of Mighty Man, there was a lot more than met the eye. Mighty Man was funded by the Apartheid government, with money shifted from the Defence budget [1].

So what did this black superhero do? Mighty Man took on many township villains and gangsters, but he was never considered ‘powerful’ enough – by his white creators, of course – to confront the white might of the South African government, which was tacitly hidden off page. A black superhero, then, but written and drawn by white hands – including a government sponsored collaboration from several rich American Republicans, keen to reinforce the status quo within South Africa.

Indeed, the comic’s aim was to “help educate the black man in the ways of Western society, social concerns and free enterprise,” as John McGoff, the American collaborator on the project, told Newsweek in 1976.

Comic books as colonising opiate of the masses.

But when it came to the Soweto Uprising, the protestors knew the tools of the state – however attractively dressed up they may have been.

South African Comics: The Past

Other far more pervasive local comic books in South Africa at the time – across Apartheid geographies – were a phenomenon known as ‘photo comics’ (also known as ‘foto novelas’ in Latin America). Instead of illustrations, they were characterised by a sequence of staged photographs with added captions and dialogues, to illustrate the scenes. They were extremely popular in South Africa from the sixties to the seventies.

“Did you ever read those photo comics they used to have in the seventies, at the cafes and corner stores in Cape Town?” I asked my partner Glenda recently.

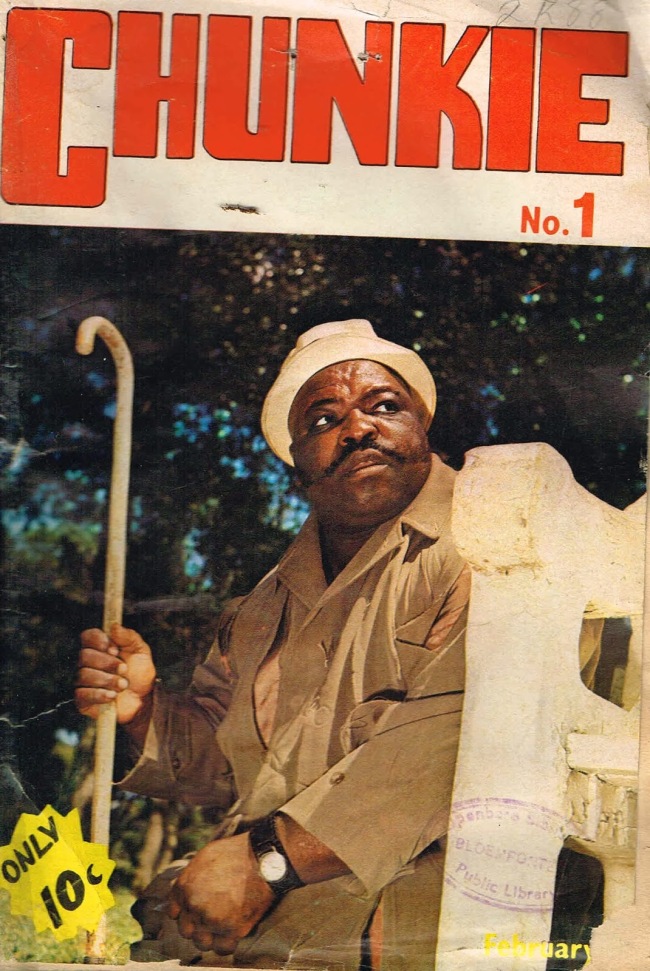

“Oh yes,” she said, “Chunkie Charlie was my favourite.”

“Who?” I said. I was stunned. I had misspent countless hours in my local café after school, reading endless varieties of these comics. Kid Colt, Tessa, Grens Vegter (‘Border War Fighter’) … I thought I’d met them all.

“You know,” she said, “the clever, rotund man with the magic coat, he had all sorts of funny things in his pockets.”

No, I didn’t know.

But then, when I listed what I had read, Glenda hadn’t seen those either.

How is it that my partner of thirty years and I could grow up within three miles of each other, and not recognise the comics we had each grown-up reading? The answer, of course, must have been in the rigid racialised geography of Cape Town at that time – and the dissemination of media (such as comics) along strict Apartheid corridors. Chunkie Charly was (in point of fact) black, and he first appeared in ‘True Africa’ – sold in the ‘coloured’ townships of Cape Town, such as Salt River.

As for me, in the privileged neighbouring garden village of Pinelands, I was ushered wherever the white imagination might best be taken in order to reinforce the establishment: to an uncritical, unreconstructed Cowboy West, where Kid Colt gunned down ‘baddies’ and ‘the Other,’ or to the (then) South West African/Angolan border, to fight in a ‘just war against terrorists.’

As the seventies boiled into the State of Emergency eighties, small pockets of internal white resistance emerged, such as the ECC (End Conscription Campaign) and, in the form of comics, a sequence of six titles called the Pre-Azanian Comics – or ‘PAX’ – which included the work of black writers and illustrators. The title alone was a dangerous statement of purpose, since ‘Azania’ was the new name posited for a post-liberated South Africa by banned underground organisations such as the Pan African Congress.

One of the key contributors to PAX was Andy Mason, who has since written an excellent overview of cartoons (and some comics) in South Africa (see Mason (2010)). PAX was polemically political in tone and written and drawn in the style of ‘underground’ comics from the sixties counterculture in the West. Andy has also written (under his pseudonym ND Mazin) several wonderful local graphic novels, such as The Legend of Blue Mamba, a dark deconstruction of the Durban surf scene and beyond. The print run of PAX was small (300) and after reading four of the six issues, I surmised they had escaped banning on the basis that they had not been noticed.

Andy also did the cover art for Roger Lucey’s ground-breaking, troubled anti-Apartheid album of the early eighties, The Road is Much Longer. Roger’s music career was systematically destroyed by the Special Branch, the South African secret police, who stalked and sabotaged him, and vandalised his house in the night. (If Roger had been black, he would have been detained and interrogated, almost certainly tortured). An online documentary of these events is available for free view, entitled Stopping the Music: A Story of Censorship in South Africa (Lucey, 2009).

Speaking of music, one of the stories in the Nommo Award winning graphic anthology The Corpse Exhibition (see more below) includes a tribute to Yakhal’ Inkomo (‘The Bellowing Bull’), the brilliant jazz album released by Winston Mankuku Ngozi in 1968. As Hawkins (2018) outlines, in a fifty-year retrospective critique of this largely forgotten South African jazz gem, Ngozi’s album was a tribute to black pain, in the moment of hopelessness between various treason trials (including Rivonia, where Nelson Mandela and others were sentenced to life imprisonment) and the later consolidated rise of the Black Consciousness Movement.

And, as internal resistance grew and external sanctions mounted, the white state eventually capitulated, so that by 1994 the first democratic elections took place and Apartheid – in legislation at least – was abolished.

Fast forward to now.

Given I have not been living in South Africa for a while, I have asked Mahdi Abrahams – proprietor of local Cape Town comics shop The Readers Den, a place I have frequented often since the early nineties – to answer a few questions on the current local comics scene.

NW: What’s your view on the development of local SA comics over the years?

MA: It has been amazing, a definite growth in the number and diversity of comics produced over the last twenty years or so, almost all of them independently printed or published due to the lack of resources and infrastructure to support any growth, and no support from the publishing world. Also, great to see a lot of material not merely attempting to copy the American model and accompanying superhero genre. The talent in SA is incredible, particularly from artists, with writing skills still rather lacking though.

NW: Over 2018, what have been the stand out local comics – and why?

MA: Sophie The Giantslayer #4 by Kay Carmichael, the latest volume in the series. It’s simply intelligent storytelling and engaging art and geared towards a young female readership, a demographic too often neglected.

Sector #10, a mixed mostly science fiction anthology released every second month, which in itself is a feat, as it sticks to this schedule (mostly). Most contributors are old hands in the local comics scene, so each issue is consistently polished. Seriously in need of a publisher, though!

Kwezi Vol 4, the only local comic series with an actual publisher, and nationally distributed. The creator and chief artist, Loyiso Mkize, is an accomplished fine artist, and it shows in this labour of love. This series manages to capture the classic superhero genre but with a decidedly local flavour.

What all of the above have in common is consistency, all are series which have managed to remain afloat beyond a mere fly-off-the-cuff one-shot!

NW: Do you see a trend in local comic publishing now – and for the year(s) ahead?

MA: There is growth, often spurred on by comic related events throughout the year. The best trend to note is the escalation of interest from readers and an actual fanbase for many of the publications. It is heartening to see quite a few local creators selling out their inventory at the end of a show. This bodes well for the future. All that’s needed is interest from publishers, so that the distribution hurdle can be overcome.

NW: Tell us more about your annual comic event too.

MA: As I mentioned, annual comic events give local comics a boost by providing a ready-made audience and awareness. Not to blow our own horn, but the annual FanCon show has, since the inaugural convention in 2016, given a much-needed platform to local comic creators. It now features the biggest artist alley in SA, with booths taken by artists from all over southern Africa. The 2019 event already has over 20 planned local comic launches.

With many thanks to Mahdi!

South African Comics: The Present

The rise of local comics is linked to increased information technology access, including smart phones. So, the current South African comic book scene looks lively, but it is also somewhat hampered by the lack of bigger publishers, that could potentially add heft and distribution to the industry.

Problems around lack of publishing options sent heralded local comics writer and illustrator Joe Daly overseas. Joe has found, like some prophets of old, honour outside their country – he’s published by Fantagraphics in America. Funny, surreal, smart – just read Scrublands for a start. The SFF novelist Lauren Beukes recently wrote a Soweto-based Wonder Woman story for DC Comics (see Beukes, 2015).

Another recent local comic I have read and been impressed by is Mengelmoes (‘Mishmash’). This is about growing up in South Africa from the 1990s and onwards. This is a clever and often funny retrospective written by Willem Samuel who is, so I’ve heard, the son of the famous Afrikaans author and poet Antjie Krog.

Soccer Warrior by Mambo Media follows the adventures of Vusi Vuzela, from his humble beginnings growing up in a rural township, to finding success as a soccer superstar. Vusi inherited an ancient kudu horn amulet from his grandfather, which grants him the amazing spiritual powers and abilities of the ancestral guardians. Vusi accepts the responsibility of these fantastic gifts, using them to help others and to put a stop to the evil plans of the dark forces he encounters. (An intriguing South African variation of Billy’s Boots perhaps, for those old enough to remember those stories, which migrated from Tiger to Roy of the Rovers?)

There is an interesting shift of the origin story from Mighty Man to Vusi Vuzela. Mighty Man, being written and illustrated by white men, had his beginnings in an alien serum, a scientific source story akin in some way to the origin of Captain America. Several western super-heroes have inherited their powers inadvertently from scientific accidents or technological mishaps, such as the Incredible Hulk, Spider-Man and Daredevil. Vusi Vuzela, however, has had his powers passed on by his family and his connection to his ancestors, and are spiritual in origin. This is a different epistemological tradition, but one rooted in connection and meaning, rather than the caprice of an out of control technological society.

And, speaking of science and differing discourses – in this case racialised – Coloureds by The Trantraal Brothers is a beautifully moving portrayal of life on the Cape Flats with an implicit politicized edge. Some UK readers may not appreciate that the title is not the overtly offensive and derogatory term that it would be in the UK or US, but rather names a wildly heterogeneous group of mainly Afrikaans speaking South Africans of diverse (‘non-white’) heritage. But nor is it a completely unproblematic term in South Africa, either. My partner, Glenda, certainly hates the term, as it has Apartheid resonances, and she is angry that the main racial classifiers have been kept after liberation, as if reifying and validating the reality of ‘race’ during the Apartheid years.

Indeed, at time of writing (April 2019) a group of white academics from the University of Stellenbosch near Cape Town, have published an article in a Western science journal (with a considerable designated ‘impact’ factor), entitled: ‘Age and education-related effects on cognitive functioning in Colored (sic) South African women.’ [2] On the back of a very small and marginalised local sample (n=60) and using a test from Montreal, Canada, they infer cognitive decline/deficit amongst these women and, by implication, beyond. HF Verwoerd, one of the main instigators of the apartheid policies in South Africa (1948-1994), was a psychologist and an assassinated Prime Minister (d.1966), who had used such flawed, race-based research to justify separate but not equal systems; i.e. ‘non-whites’ as ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water.’

One black historical figure from South Africa who went far beyond such racist stereotypes was Shaka Zulu. There is a refreshingly well-done local retelling of the life of Shaka Zulu (c.1787–1828), by Luke Molver and Mason O’Connor (2018). The warrior, king, and brilliant military innovator, Shaka Zulu, has been much discussed in South Africa. He built up the Zulu peoples from a small local clan to a regional ‘Empire’, via an expansion known as the Mfecane (or ‘Crushing’), that ended up challenging even the vastly superior fire-power of the colonising British. (The ugly racist discussions and text books in the white school I attended in the seventies, however, referred to him as ‘a black Hitler.’ Presumably empires only carry legitimacy if they are white?)

Molver and Mason’s Shaka Rising, for its part, is a beautifully told, nuanced tale that retains its African centre and refuses to succumb to the White Gaze. A tale told on its own terms, but not afraid to include the ‘warts,’ [3] which are carried by all of us, at some time or another. So yes, Shaka could be brutal, like so many of us – but he was also loyal, brilliant in diplomacy – and he strengthened the social as well as military ties within Zulu culture. So, a flawed but powerful indigenous hero. As, Molver (2018) stated: “Also, with the phenomenal success of movies like Black Panther, and the renewed interest around African speculative fiction in general, I believe this is a very good time to be putting out these comic books.” Indeed, the 2018 Marvel hit Black Panther contains at least one or two direct allusions to Shaka Zulu’s life.

Rob Malan’s Quest and the Sign of the Shining Beast was deservedly shortlisted for the Nommos – the African Speculative Fiction Awards – in 2018. A haunting juxtaposition of illustrations from John Cockshaw, alongside Rob’s sharp text and imagery, carry you tensely along the fraught journey of discovery.

Speaking of the Nommos, the inaugural (Graphic Novel) Nommos in 2017 was won by the brilliant Chimurenga (‘Struggle’) publication from Cape Town: The Corpse Exhibition and Older Graphic Stories. It’s a dark and beautiful mix of the surreal and the fantastic, including narrative illustrations of Ghanaian SF author Kojo Laing’s classic Major Gentl and the Achimoto Wars by Nikhil Singh (2018), himself also an author of note – check out his novel Taty Went West (2015).

And, almost finally, we started with an old black South African superhero Mighty Man [4] and end with an exciting new one (already mentioned by Mahdi above): KWEZI. This comic has been gaining a lot of traction. It’s got high production values and is an exciting development in South African comics. A young local hero written and drawn by a local talent growing in stature – Loyiso Mkize. Loyiso also drew a harrowing version of the Marikana Massacre from 2012, in The Corpse Exhibition.

In addition, Zimbabwean Bill Masuku’s Captain South Africa has been taking off too, launched at the inaugural Comic Con Africa – see Davies (2018, including images) and Watson (2019) for more details. Captain South Africa is indeed a superhero with a difference, she uses non-violent and empathic ways of confronting issues and ‘villains,’ and discusses, amongst other topics, the failings of Nelson Mandela.

These are now black superheroes owned by black writers and not co-opted by the – still predominantly white – publishing platforms.

For, despite some good changes over the past quarter of a century – i.e. since the first democratic elections in South Africa – white privilege and gatekeeping is still a feature in areas of the local literary establishment, despite valiant efforts by many to address this. And so, back to Soweto – a Soweto no longer in flames, but the venue for the Abantu Book Festival, established by Thando Mgqolozana (2016) amongst others, with the aim to decolonise South African literature and celebrate black writers and readers, in the wake of the Rhodes Must Fall movement (Sandwidth, Soldati- Kahambaara, & Fassalt, 2018).

Kiguru (2019) is attempting to network local ‘non-mainstream’ indigenous literary establishments, such as Chimurenga (above) and Kwani in Kenya (amongst others) as a means of building and centralising local knowledges, discourses, and productions. This is extraordinary work being done by ordinary people to reconstruct the world in a more representative and equitable fashion.

So, finally, to a couple of the ‘ordinary superheroes’ in South Africa. Mogorosi Motshumi is the first black South African to write a graphic novel autobiography. The Initiation (2017) is his opening salvo in ‘The 360 Degrees Trilogy’. In it, he recounts his political awakening and involvement with the Black Consciousness Movement, during the Apartheid years. As Khan’s (2017) review stated: ‘Blame Me on History.’

Finally, in 2017 Ziphozakhe Hlobo and Lean Posch launched a comic on ‘ordinary superheroes’ in Khayelitsha, a large township in Cape Town. The comic, titled Khazimla’s Adventures, is inspired by Monde Sithole, “an adventurer, educational strategist, and futurist.”

The synopsis reads: “Themba grows up haunted by dreams of ‘otherworldliness’ and adventure, a complete juxtaposition to the limitations of the township gang violence he finds acceptance and excitement in. He will soon discover another world that lies beneath the surface of the dusty streets and enter a journey to the mountain of self-discovery and transformation. But, as with all fulfilling journeys, it will not be without turbulence, which he must overcome.”

For more on Ziphozakhe, read Geoff Ryman’s (2017) interview with her in Strange Horizons. Ryman has also got permission to publish Part One of the comic in The Manchester Review (Hlobo and Posch, 2018).

From superheroes to the ordinary heroes around us. As Ziphozakhe says, “Everyone has a dream,” and “before colonisation Africans were grounded in nature.” So, as we all face a natural world increasingly fraught by fire and climate catastrophe, may the ‘ordinary’ people of the world – which includes the marginalised and dispossessed – unite, both in collective dreams and collective action for a better, fairer, and greener world.

For now, indeed, the whole world is going up in flames, in a massive conflagration Amitav Ghosh (2016) has hitherto referred to as The Great Derangement. Ghosh perceived we will indeed look ‘deranged’ to future generations confronting climate catastrophe, in our current institutional and blinkered climate denial or minimisations. That is, unless enough of us start waking up to the Extinction agenda and the thunder of truth from a sixteen-year old Swedish ‘girl’. An ordinary hero, for our extraordinary times. Of such, are great comic books made.

Nick Wood (2019)

References and Resources:

African Speculative Fiction Society. http://www.africansfs.com/

Beukes, L. (2015) Wonder Woman in Soweto. Brittle Paper. https://brittlepaper.com/2015/03/woman-soweto-lauren-beukes-african-spin-dc-comics-sensational-classic/

Davies, D. (2018). Genre, Politics, and Southern Superheroes: Review of Bill Masuku’s Captain South Africa. Africa in Words. https://africainwords.com/2018/10/29/genre-politics-and-southern-superheroes-review-of-bill-masukus-captain-south-africa/

De Villiers, J. (2018). The apartheid government created a black superhero called Mighty Man – and in 1976, black youth set him on fire. Business Insider South Africa. https://www.businessinsider.co.za/apartheid-government-spent-millions-educate-black-man-comic-youth-day-2018-6

Ghosh, A. (2016). The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. University of Chicago Press.

Hawkins, S. (2018). Yakhal’ Inkomo: A South African Masterpiece at Fifty. All About Jazz. https://www.allaboutjazz.com/yakhal-inkomo-a-south-african-masterpiece-at-fifty-winston-mankunku-ngozi-by-seton-hawkins.php

Hlobo, Z. and Posch, L. (2018) Khazimla’s Adventures. In Ryman, G. (2018) The Manchester Review, 18, http://www.themanchesterreview.co.uk/?p=7720

Khan, A. (2017). Blame Me on History. The Chronic. https://chimurengachronic.co.za/blame-me-on-history/

Khubeka, A. (2018) Shaka Brought to Life as Comic Book Hero. Independent on Sunday. https://www.iol.co.za/ios/arts/shaka-brought-to-life-as-comic-book-hero-16165896

Kiguru, D. (2019) Literary Networks and Collaborations: A Nod towards Knowledge Decolonisation. Africa in Words. https://africainwords.com/2019/01/11/literary-networks-and-collaborations-a-nod-towards-knowledge-decolonisation/

Laing, Kojo (1992). Major Gentl and the Achimota Wars. Heinemann Educational Books.

Lucey, R. (2009). Stopping the Music: A Story of Censorship in South Africa. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=btyYT9IPrig

Mason, Andy (2010) What’s So Funny? Under the Skin of South African Cartooning. Cape Town: Double Storey. Or Mazin, ND, (Personal Website) http://ndmazin.co.za/onlinebooks/the-legend-of-blue-mamba/

Mazin, N.D. (2018) The comic absurdity of Day Zero. Daily Maverick. https://www.msn.com/en-za/news/dayzero/the-comic-absurdity-of-day-zero/ar-BBJA6Yn?li=BBqfP3n&parent-title=10-ways-to-love-your-man&parent-ns=ar&parent-content-id=AAlD4YH

Mgqolozana, T. (2016). How can we decolonise SA literature? Mail & Guardian, https://mg.co.za/article/2016-03-14-author-mgqolozana-how-can-we-decolonise-sa-literature

Molver, L. & O’Connor, M. (2018) Shaka Rising. Story Press Africa. https://www.catalystpress.org/young-adult-books/shaka-rising/

Pijnaker, T. (2018a) African Superheroes Blog Series: Introduction – What is an African superhero? Africa in Words. https://africainwords.com/2018/05/21/african-superheroes-blog-series-introduction-what-is-an-african-superhero/

Pijnaker, T. (2018b) African superheroes in the 1970s and 1980s: a historical perspective. Africa in Words. https://africainwords.com/2018/06/11/african-superheroes-in-the-1970s-and-80s-a-historical-perspective/

Ryman, G. (2017) Ziphozakhe Hlobo. In 100 African Writers of SFF. Strange Horizons. http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/ziphozakhe-hlobo/

Saint, L. (2018) Afri-Comics in the Afterlife: An interview with Wiliiam Worger. Africa in Words. https://africasacountry.com/2018/08/afri-comics-in-the-afterlife

Sandwith, C., Soldati-Kahimbaara, K., & Fasselt, R. (2018). Decolonizing the reading landscape: A conversation with Kgauhelo Dube. The Journal of Commonwealth Literature. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021989418787580

Singh, Nikhil (2018). When Taty Went West. Rosarium Publishing.

Watson, MJ (2019) Brainwavez: A Collective. https://www.brainwavez.org/ (A wonderful web news repository for comics and gaming in South Africa.)

Wood, N. (2011) Soweto’s Super Man: ‘Mighty Man’ and the mid-70s in South Africa. South African Comic Books. http://southafricancomicbooks.blogspot.com/2011/10/sowetos-super-man-mighty-man-and-mid.html

Notes:

[1] I tell a fuller version of this story on South African Comic Books, run by fellow collector George van der Riet (Wood, 2011). De Villiers (2018) has updated and extended my account for Business Insider, under the title ‘The apartheid government created a black superhero called Mighty Man — and in 1976, black youth set him on fire.’ Eleven out of seventeen of the (now very rare) Mighty Man issues can currently be read in full, online at: (idep.library.ucla.edu/afri-comics), carefully digitised by Professor William Worger at UCLA.

[2] Boswell (2019). Letter to the Editorial Board of Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition. awethu.amandla.mobi/petitions/letter-to-the-editorial-board-of-aging-neuroshychology-and-cognition-1. The article has since been retracted, following a petition that meticulously exposed its methodological flaws and pointed out its overall racist underpinning.

[3] ‘Warts and all’ from Oliver Cromwell (England, 1599-1658), a controversial figure who asserted the rights of the English Parliament against the dictates of monarchy. His warts, however, were also many.

[4] Africa in Words (Lily Saint) interviewed Prof. William Worger (UCLA) on Mighty Man.

This article first appeared in issue 289 of Vector.

I HAVE 4 COMIC FROM SOUTH AFRICA BITTERKOMIX i have von 4 to 7 wondering if they are worth anything they are in africarn but in mint condition

I am a graphic novelist and need to know of publishing options.