Eugen Bacon is an award-winning writer of speculative fiction and non-fiction. Her works include Claiming T-Mo (Meerkat Press 2019), Writing Speculative Fiction: Critical and Creative Approaches (Macmillan 2020), Inside the Dreaming (NewCon Press, 2020) and Hadithi and The State of Black Speculative Fiction, a forthcoming collaboration with Milton Davies (Luna Press, 2020). In this essay, she reflects on some of her favourite black speculative fiction.

As an African Australian who’s grappled with matters of identity, writing black speculative fiction is like coming out of the closet. It’s a recognition that I’m Australian and African, and it’s okay—the two are not mutually exclusive. I am many, betwixt, a sum of cultures. I am the self and ‘other’, a story of inhabitation, a multiple embodiment and my multiplicities render themselves in cross-genre writing. As a reader, writer and an editor, I’m increasingly noticing black speculative fiction, and it’s on the rise.

It’s not like black fiction was never there. I was always an avid reader from childhood, and my father rewarded my curiosity and good grades with African writing. I honed my tooth for literature on Margaret Ogola, Chinua Achebe, Camara Laye, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. Their writings are not always considered as parts of the speculative genre, but I was introduced through their novels to narratives with roots in traditional beliefs and oral literature. Growing up, I revelled in fairy tales featuring protagonists from the insect and animal world—like the clever little monkey or the wise tortoise or Ananse the clever spider—in ‘how’ and ‘why’ stories: How the frog came to be the king of the rivers and marshes / How the tortoise got its scars / How the tortoise beat the hare in a race / Why the bat flies at night / Why the crab has no head…

Picture my delight years later in the editorial team of Aurealis, Australia’s most successful speculative fiction magazine, when I stumbled across British-Nigerian writer Nuzo Onoh’s African-hued ‘Ogali’, an exemplar of black speculative fiction with its setting in a village and its use of the fantastical through black magic. The story opens tautly, at once immersing the reader into the concept of a dreadful happening:

Ogali died on the dawn of her fifteenth birthday. She died gripping the wrist of the young man, Amobi, he of the roving eyes and honey-sweet tongue. Amobi swore he was not near her when she died, that he was with another virgin at a different village, engaged in the pleasures of the groin at the time of Ogali’s death, just before dawn.

Skilful in writing this short fiction, Nuzo Onoh pays attention to world building, characterisation, tension, theme and the ‘alternate’ in convincing speculative fiction. We encounter the village and the tiny room that houses a young girl’s corpse, and the centre of the hamlet where a crowd gathers to witness black magic. The witchdoctor and his chanting urge the petrified young man to confess his crime:

Amobi, son of Obioha of Okoro clan, lift your shameless bottom from the floor and explain yourself to us before I curse you with the itchy pus-penis and eternal sterility, you disgraceful scoundrel.

Tension builds with the exploration of the young woman’s death, and Amobi’s possible hand in it. Tension peaks to a climax when the dead body acts on its own in supernatural ways to draw attention to its killer.

The story bears elements of fantasy in the bizarreness of Ogali’s sickness, the invoking of the occult, in the use of black magic (the slaughtering of cockerels), and reanimation—all working well to summon dread or foreboding in the reader. In its integration of fantasy, horror and the paranormal, ‘Ogali’ is also a good example of fiction that crosses genre and will remain one of my favourite stories.

Onoh is a pioneer of African horror and her work is published in several anthologies, including the upcoming Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora—with stories in the sub-genres of horror noire, Afrofuturism, sword and soul, steamfunk and dieselfunk.

Another work of fiction that I really took to is a young adult novel Catching Teller Crow (2018) by the Aboriginal Australian writers Ambelin Kwaymullina and Ezekiel Kwaymullina. I first came across it as a judge in the Aurealis Awards. It’s an ingenious story told in shifting first-person perspectives, where the brother and sister duo grasp the tactic of stories-within-a-story in unison as the unreliable narrator. The novel borrows from the indigenous art of oration to tell a perturbing tale that’s also ghost fiction. It adopts the levity of prose poetry and song to weave evocative imagery and personification in accessible language, while playing out robust themes on the abuse of power, and tackling ideas that might affect adolescents. Opening with the concept of death, the story introduces us to protagonist Beth, the spirit of a dead girl. The characters in the story package a horrendous tale, whose sombre themes are productive elements of young adult fiction, and herald change.

We see the world from the perspective of the victims and it’s more than just another story. Catching Teller Crow is a tale of courage, of remembering who you are. It takes a closer look at Australia’s shameful past of the Stolen Generation by exposing Nanna’s strength—the little black girl who found her way back, years after the government took her away from her mother. It is a very dark tale but it’s also a story of hope that builds into the protagonist and her friends a quest for more. It wraps them up with good friends and, together, they understand a craving for transformation that morphs Catching Teller Crow into a story of survival, of selfhood, of identity.

Towards the end, Beth and her father Michael and her newfound friends experience a full-circle transformation archetypal to a hero/ine story. In this cross-cultural narrative, we see a different kind of writing. It is a new kind of book that brings out something special. It breaks the circle of silence and roars up deep anger, depression and confusion, before humming a tune of self-awakening and the kind of reflection that haunts.

Unsurprisingly, the very personal story that’s also universal despite its black protagonist snapped up a few awards and was nominated in several literary longlists and shortlists, and won the Victorian Premier YA Prize for Literature and Best Young Adult Novel at the Aurealis Awards.

Franz Kafka, a German-speaking Bohemian novelist and short story writer, widely regarded as a major figure of 20th-century literature, famously wrote:

…we ought to read only the kind of books that wound or stab us. If the book we’re reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow to the head, what are we reading for?

… A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us.

This was the axe that struck me when I read Namwali Serpell’s debut novel The Old Drift (2019) that won the Los Angeles Times Art Seidenbaum and was a finalist for the inaugural Los Angeles Times Ray Bradbury Prize. It was also longlisted for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize. This black speculative literary fiction grabs you from the first line, ‘Zt. Ztt. ZZZzzz…ZZZzzzzo’na,’ and enslaves you beyond its finish. It’s a fantasy so subtle, it’s extreme; a romance so fragile, it’s lush; a political arena so subversive, it’s sensational.

It’s the language and the body of astonishments concealed in the rebellious and lengthy text that charmed me. Serpell explores ideology, disease, curiosity in relationships forged and lost. She casts a spotlight on the place of women in society, on the intolerable choices of mothers and their children, on the quest for identity, and a search for belonging.

Afrofuturistic in its gaze at colonisation, independence and a futuristic continent, the novel interrogates the challenges and intricacies of converging cultures. A vicious book, it hurls upon its gullible cast the cruelty of fate sprinkled with impish humour—enticing even in its secondary characters like the Lusaka housemaid Grace who calls bedsheets shittybeds in the thinness of her borrowed language. The Old Drift is a thoroughly researched novel, a fiction of fictions, a poignant grandiosity lavish in language and a magnificent intimacy with Africa—a continent of pent up resentment finally bellowing in rage.

Serpell is a Zambian writer and a professor who teaches at the University of California Berkeley. She received a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award for women writers in 2011 and was selected for the Africa 39— a 2014 Hay Festival project to identify the best African writers under 40. Her first published story ‘Muzungu’, which means ‘white man’ in a few tongues including Swahili, was selected for The Best American Short Stories 2009 and shortlisted for the 2010 Caine Prize for African Writing. She won the 2015 Caine Prize for her story ‘The Sack’.

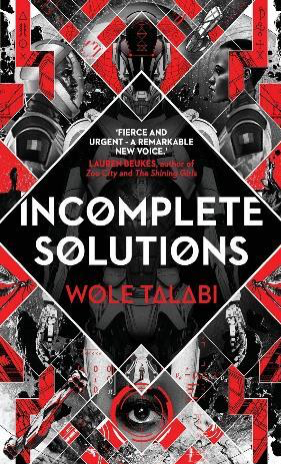

Another work I can’t help raving about—it so thrilled me, I nearly burst into song—is Wole Talabi’s bold and playful Incomplete Solutions by Luna Press Publishing. Reading the collection took me back to Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison’s playfulness with language or French literary theorist Roland Barthes’ le plaisir du texte. As Barthes would have it, fiction is a figment of our imagination, text is a tissue of quotations, arising from thousands of sources of culture, and both the writer and the reader extrapolate meaning from it. Talabi encourages this extrapolation in his experimental collection of short stories that are sharp and brisk, and others that linger in a narrative style that arrives with metafiction, where an insightful narrator hauls the reader, sandals and all, into a weird but captivating telling.

Talabi is not your typical short story writer. He transports you on a strange, transcultural odyssey filled with Yoruba mythology and nested logic, with recurring themes of the unknown, variability, equation, relationship, sacrifice, betrayal, transposition, escapade… His stories subvert the reader’s expectation. You’ll find gods and goddesses, victims and victors, beings that are ‘alters’—other versions of you in virtual reality twists and cyber consciousness. The sensitivity and perception within the writing, where each story is a question or a curiosity, a possibility where an answer is irrelevant, will stay with you.

What I realise in these readings, and more black speculative fiction out there, is the important conversation on Bla(c)kness. I remember the last of my writerly engagements early in 2020 before COVID-19 impacts on the creative industry became obvious and a cascade of event cancellations happened. A writing organisation in New South Wales, Australia, invited me to participate in its Talking Writing series, that session featuring Africa. With a black panel curated and chaired by the actor, writer and activist Moreblessing Maturure, and funded by the Copyright Agency Cultural Fund, the conversation gave voice to the hierarchies of blackness in Australia and cast its gaze on the complex and diverse experiences of African migrants and Afro descendant peoples relative to indigenous peoples. Post-event, participants from ethnic minority groups, some with Lebanese, Israeli and Cambodian heritage, shared how insightful it was to find writing that featured an ‘other’ because they were always trying to ‘fit in’.

In the self and ‘other’, my story of inhabitation, I am not alone. The speculative invites bending genre, offering up writing that subverts the reader’s expectation by deconstruction, breaking boundaries in experimental, adventurous fiction that gives an opening to the black voice. I’m thrilled that more black writers are inventing the self, actively speaking, tuning basic drives and curiosity about culture and identity into creative and intellectual energy. Readers and publishers, irrespective of race, are finding fascination in black speculative fiction, and there are even exclusive awards such as the Nommo Awards that recognise works of speculative fiction by Africans, judged by African writers, from the African Speculative Fiction Society.

The fictions I have shared in earnest with you in this article are simply exemplars of diverse black writing out there. With a growing openness in publishers to look at a different kind of story and attract black writing, there is an unquestionable rise of black speculative fiction in the market, and this is a wonderful thing for people of colour who are looking for stories that feature a relatable ‘other’ like them. I recently wrote an essay in collaboration with African American publisher, editor and author Milton Davies, titled ‘The State of Black Speculative Fiction’, coming out in a hybrid project titled Hadithi by Luna Press Publishing this winter (not the Aussie one). The essay opens dialogue about Afrofuturism, speculative fiction, crossing genre and fiction by black writers. The abstract reads:

As speculative fiction authors are increasingly curious and experimental in a competitive publishing industry, crossing genres to subvert the reader’s expectations, writers of colour are ever more claiming their right to tell their own stories in invented worlds with characters they can identify with. This new brand of writing is taking form in small press afrofuturistic dystopias, myths and epics delivered to a growing readership that is open-minded and inquisitive. But, until black speculative fiction is normalised, there’s still a long way to go.

We need more publishers to step up and encourage writing that gives voice to minority ethnic groups. Black speculative fiction is out there—you’ve only to seek it. So, we also need a growing readership that is curious and welcoming to this new brand of Afrocentric writing by authors whose text is betwixt, a sum of cultures. Until more readers, publishers, agents and literary award judges start paying notice to stories of inhabitation, multiple embodiments, black speculative fiction that is inclusive in its crossings across cultures, the rise of this calibre of fiction will linger along the margins.

Reblogged this on Loving Life in the Rain.