By Paul Kincaid

There is no particular issue with the timeline of the original 1973 film, Westworld, written and directed by Michael Crichton. It is set in the then near future, 1983, and the linear action takes place entirely within the Delos theme park. But when the film became the basis for the television series created by Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy, Westworld (2016-present), time became a complex and confusing issue.

Nolan had already displayed a rather cavalier attitude towards time in his earlier television series, Person of Interest (2011-2016). The first series, first broadcast in the autumn of 2011, was set in 2012, but contained multiple flashbacks to events over the previous decade. Although these flashbacks are often dated, it can be difficult to construct a coherent timeline for the two principal characters, Harold Finch (Michael Emerson) and John Reese (Jim Caviezel). But when it came to Westworld, that tendency to play fast and loose with chronology became an often understated but defining characteristic of the series.

To date there have been three series of Westworld (it has subsequently been renewed for a fourth season). For convenience I will refer to Westworld Season One: The Maze as WW1 (2016), Westworld Season Two: The Door as WW2 (2018), and Westworld Season Three: The New World as WW3 (2020), each of which presents time in a different way, even though theoretically each is a direct sequel to the series before.

Of the three, WW1 seems to have the simplest chronology. There is a central story in which Ford (Anthony Hopkins), one of the two creators of the park, is concentrating on building a new story for the hosts, the androids that populate the park. In this Ford is assisted by his Head of Programming, Bernard (Jeffrey Wright). During the course of the season, Bernard slowly discovers that he is, himself, a host, based on Arnold Weber who co-created the park with Ford. Though there are occasional flashbacks, this story, which appears to form the narrative spine of the series, is presented more or less chronologically. The other stories that accumulate around it, therefore, which involve two of the hosts, Dolores (Evan Rachel Wood) and Maeve (Thandie Newton) gradually acquiring independent consciousness, would appear to fit within the same timeline. The stories of Dolores and Maeve are themselves set within the stories of two visitors to the park. William (Jimmi Simpson) is a young man on his first visit to the park, rather hesitant in his dealings with the hosts and initially shocked by the brutal, careless manner of his companion, Logan (Ben Barnes). Logan is heir to the company that runs Delos, and William is clearly being groomed to rise in the hierarchy. In contrast, the man in black (Ed Harris) is an ageing habitué of the park who returns regularly, raping and killing the hosts with glee.

Interspersed among the scenes within the park, which recreates the wild landscapes and rough towns of the American West in the late-19th century, there are scenes within the Delos facility which is very futuristic and antiseptic with its bare corridors and glass-walled rooms within which the naked hosts can be seen undergoing a variety of medical or indoctrination procedures. It is here that we see Dolores and Maeve, during the procedures that follow them repeatedly being “killed” in the park, coming to independent awareness and increasing control of themselves and their surroundings. Meanwhile, Delos personnel, such as scriptwriter Sizemore (Simon Quarterman), Head of Security Stubbs (Luke Hemsworth) and Executive Director Hale (Tessa Thompson), start to become aware that the hosts in the park are not behaving the way they should. Since both the story arcs that take place within the facility seem to be simultaneous, it adds to the impression that the whole of the series takes place within a fairly compact timeline, a period of perhaps a few months.

Then we discover that William and the man in black are the same person. The whole series, in other words, has actually taken place over a period of at least 20 years, during which time the relatively naïve William has grown into the ruthless businessman who has seized control of Delos. When WW1 climaxes with Dolores killing Ford in the middle of the grand opening for his new scenario, it launches an uprising of the hosts that has been far longer in gestation than the series might have us believe.

Even though this revelation has warned us not to believe anything the series tells us about time, the chronology of WW1 still seems fairly straightforward, and there is no reason to assume that that will not continue into the second season. WW2, after all, begins at the exact point that WW1 ends, with the massacre of guests at Ford’s ill-advised launch party, and the whole season would seem to take place over a matter of weeks, at most. Certainly the action strands come fast and furious, as the militarised security force for Delos try to wipe out the rebelling hosts, and the hosts either fight back or attempt to escape. The primary escape plan involves the opening of a door in the middle of the American wilderness, through which the majority of hosts pass. As they go through the door their bodies fall away, as though they have jumped from a cliff, but their identity is translated to a new digital matrix, the Sublime, (perhaps a nod to the work of Iain M. Banks) that is inaccessible to humans. Meanwhile the human survivors are gathered together and evacuated from Delos by boat (we learn at this point that Westworld is actually located on an island, though an island so large that its fringes have not previously been discerned, as if geography is subject to the same flexibility as time). Paralleling the passage of the hosts through their door, the humans boarding the boat are travelling to a reality that is presumed to be inaccessible to hosts.

These two escapes, coming together at the end of the season, seem to neatly enclose the action of the season: it began with the massacre and ends with the escape of the survivors, and the whole season would therefore appear to occur within this narrow timescale. Except that this timescale does not, and cannot, encompass all that happens within the season.

Some of the alterations in the timeline come in the form of recognizable flashbacks, the most significant of which introduces James Delos (Peter Mullan), the original owner of the park who is convinced of the worth of the franchise when he sees a prototype of Dolores moving undetected among the guests at an expensive party. In this past we see James decide to make the young William his heir rather than his own son, Logan. But the story of James Delos isn’t confined to the past, it reaches into the story’s present and even, perhaps, into its future (James reappears briefly but significantly in WW3, along with young William, as a figment of William’s madness). The hosts, we are told, are part of an experiment in human immortality, and James is the subject of that experiment. We see him, time and again, in a bland, familiar room (eerily reminiscent of the characterless hotel room at the climax of 2001, A Space Odyssey (1968)) where he receives a string of visitors, including both young William and old William as an indicator of how long this experiment endures. These visitors are a test of how well the character of James has been recreated, but the test always fails and eventually the experiment is abandoned. At one point, Bernard and Elsie (Shannon Woodward) encounter the insane host of James, suggesting that the experiment had been perhaps hastily abandoned not long before.

The personalities, indeed the continuing identities of the hosts are contained within a device about the size and shape of a golf ball known as a pearl. The story of James Delos seems to indicate that the personalities of real humans cannot be reproduced in the same way. Except that we have known since WW1 that that is not the case, after all Bernard is a host bearing the personality of Arnold, and at one point during WW2 Bernard discovers Ford’s persona among the back-up pearls of other hosts, a persona necessarily recorded and available while Ford was alive. We see Ford as a child in the park, though the child is a host, and right at the end of the season there is a suggestion that William is also a host. So those who keep James imprisoned as part of a perennially failing experiment are doing so after that same experiment has been successfully achieved and apparently on multiple occasions. (The suggestion that William is a host is part of the general inconsistency of the series, since the William who appears in WW3, while certainly mad, is inarguably human; though that series ends once again with the suggestion that William is a host.)

What I have laid out so far is only part of the temporal inconsistency of WW2. The three hosts who are central to the story, Dolores, Maeve and Bernard, each pursue their individual goals throughout the season. Maeve sets out to find her daughter, a quest that takes her to other parks, most notably Shōgunworld. The other parks we see, Shōgunworld and a park based on the British Raj here, another based on the Second World War in WW3, owe more to film than history. The Native American group we follow occasionally in this season speak a genuine Native American language and have a social structure that is reasonably authentic, but their interactions with whites, either visitors or other hosts, are pure cowboys and Indians. During the course of her wanderings we see that Maeve is perhaps the most powerful of the hosts, since she seems to be able to control other hosts and eventually other Delos technology by thought alone. Dolores (Delos Or?), the most revolutionary of the hosts, is seeking a control unit that seems to be associated with her host father, Peter Abernathy (Louis Herthum). This brings her into conflict with Bernard and Hale, who are seeking the same thing. Eventually, this quest takes her to the Forge, a repository of information on the guests, which gives her the data she needs to continue her war of liberation against humanity.

Both of these strands seem to follow a fairly straightforward chronology; there is the occasional flashback, and perhaps even an odd flashforward, but essentially the main line of the stories appears pretty clear. Except that both strands intersect with Bernard at various points, and it is not clear where or when in that chronology they fit. Because Bernard’s story is frankly a mess. The story seems to dot about both in time and in space. Sometimes this is explicit, as when Bernard discovers Elsie chained up inside a remote facility and we learn that he himself was responsible for abandoning her there, even though he has no memory of doing so. At other times it is not so clear: was this episode with Bernard and Elsie before or after this episode where Bernard on his own encountered Dolores? Towards the end of the season this confusion is partially explained when Bernard scrambles his own memories before being killed by Dolores. The disorder in the sequence of events is therefore a disorder in Bernard’s own memories of them (particularly if we assume that Bernard actually represents the narrator viewpoint of the series). But does that mean that the events in the stories of Dolores and Maeve are similarly disordered where they intersect with Bernard?

The distortions of time throughout this season seem appropriate when the focus of the story is on immortality. If we are our memories, and the attention paid to the pearls containing the personae of both hosts and humans would suggest that this is the thesis underlying this season, then who are we when there is too much for us to remember? And the multiple lives not just of the hosts but of James Delos, Ford, and perhaps even William, all point to the idea that they have lived more than can be contained within one memory.

But in its final moments, WW2 changes direction, becoming more about identity than immortality. Identity is, of course, the underlying theme that runs through WW1, and hence, in the self-awareness of the hosts, the basic idea that runs right through Westworld. But in WW2 this had been not so much hijacked as narrowed down to ideas of the continuation of the self. But in its violent endings, WW2 specifically links the continuation of life to the continuation of personality. Hale is killed, but is resurrected as a host with a copy of Dolores’s pearl implanted in her; Dolores is also killed, but in the guise of Hale escapes the park carrying a supply of pearls. In her escape, Dolores/Hale is aided by Stubbs, who also turns out to be a host. And Bernard is killed by Dolores, only to be revived by her once they are outside the park.

However, any expectations this might set up about how the story would continue in WW3 are not exactly fulfilled. WW3 marks a dramatic change in the character of Westworld, in both small and large ways. It is a season of only eight episodes, as opposed to the ten episodes of both WW1 and WW2. It is set almost entirely within the real world, which means that the locations and the colour palette of the film are dramatically different. (The only extended section set in a park, ostensibly Italy under Nazi occupation though actually filmed in Spain, reverts to the dusty, faded colours of the earlier seasons.) Most significantly, the underlying theme of the season is radically different. Where the first two seasons had concentrated on technology achieving independence, and more broadly on the question of what makes us human, WW3 shoehorns into the story exactly the same issues and obsessions that had guided Jonathan Nolan’s earlier series, Person of Interest. The McGuffin in that series was a US government computer system that could access every email, computer message, CCTV camera or other features of the surveillance state in order to predict acts of terrorism and, only incidentally, other criminal acts. It was a series, therefore, that confronted, sometimes rather crudely, questions of free will, state control, and the predictability of the individual. In WW3, the McGuffin is an artificial intelligence named Rehoboam (an oblique nod towards Shalmaneser in Stand on Zanzibar (1968) by John Brunner) which can predict and therefore control the future actions of every human on Earth, therefore inevitably raising questions about free will, corporate control, and the predictability of the individual. It is, perhaps, a sign of the way Person of Interest was in Nolan’s thinking while making WW3 that the actor Enrico Colontoni, who played the crime lord Carl Elias in the earlier series, here plays the small but significant role of Whitman.

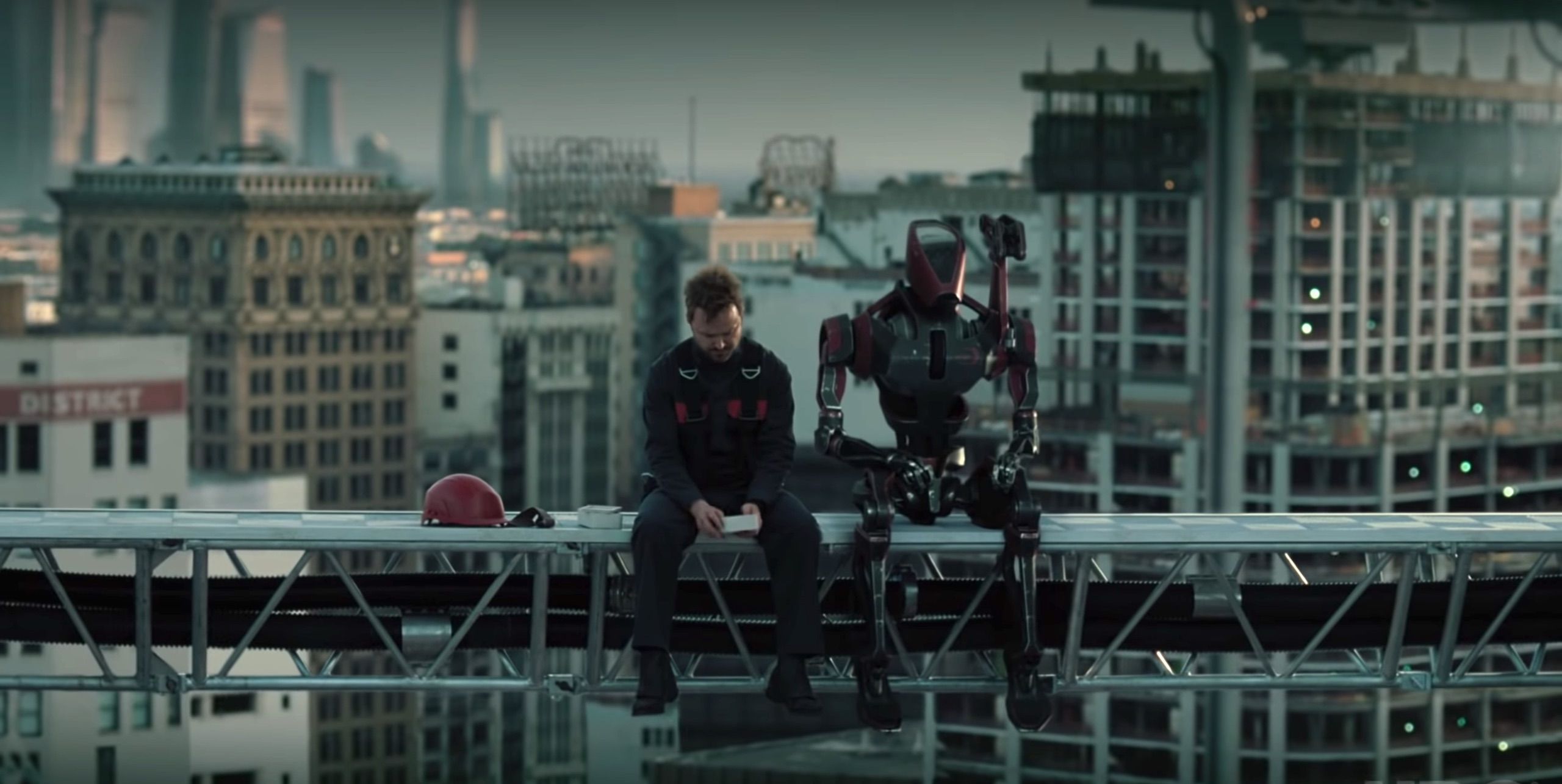

The change in direction of Westworld, the aligning of the story with a more straightforward thriller plot, makes the chronology of the season more consistent. Dolores is sophisticated and powerful, moving easily in this high-monied world, but her quest has changed slightly. Now, rather than liberating hosts from humanity, her primary concern is to liberate humanity from Rehoboam. In this she is aided by an ex-soldier and petty crook, Caleb (Aaron Paul), but also by versions of herself, humans who have been remade as hosts with copies of Dolores’s pearl installed. Maeve, still searching for her daughter, now believes that Dolores may hold the secret. Her search for Dolores aligns her with Serac (Vincent Cassel), the creator of Rehoboam. Meanwhile Bernard, aided by Stubbs, is seeking Dolores to learn what she knows and prevent the destruction of the world. Each of these is accompanied by some flashbacks, particularly in relation to Caleb, but in the main they are told in a fairly conventional chronological way, and the narratives do seem to be happening at more or less the same time. So there is no temporal confusion about the series. Nevertheless, there are occasional oddities that don’t add up, or at least that don’t seem to belong within the same timeframe as the two previous seasons.

Wikipedia, in its various entries on Westworld, is emphatic that the programme is set in 2058, though not a great deal of stress is placed on the date in the episodes themselves. Given the aesthetic of the future and the everyday technology that we glimpse particularly in WW3, a date somewhere around mid-century does seem reasonable. But the first visit to Westworld by young William, which we saw in WW1, means the park must have been up and running by the mid-2030s at the latest. The encounter with the prototype Dolores that convinced James Delos to invest in the park that would bear his name, which we saw in WW2, must have come some years before that. And we must presume that the development of artificial intelligence and the advances in robotics that would create that first prototype took a few more years. So the work that would produce Westworld must be in place by now.

None of that is anomalous, of course, but it sets a context within which we must view the chronology of the programme.

Two things that occurred within WW3 made me question that context. Both were clearly done as a way of establishing motivation for a character, but they seem to have been introduced without much thought as to whether they conflicted with the history of Westworld as we know it.

The first of these occurs when we see two young boys, probably no more than ten, playing in a field. Suddenly strange men completely encased in Hazmat suits appear and, as the camera pans round, we see what looks like a mushroom cloud rising on the horizon. This, we are told, is the end of Paris as witnessed by the young Serac and his older brother. What brought about this destruction, whether war, terrorism, accident, or what, we never learn, and the incident, whatever it might have been, is never mentioned elsewhere in the series and has no other impact on the world of Westworld. The problem is that Vincent Cassel, the French actor who plays Serac is in his fifties, and is presumably playing his age, which means that the destruction of Paris would have occurred sometime in the last two or three years. (Some might argue that this is, therefore, an alternate history, but that is truly a lazy excuse rather than a serious reason for the inconsistency.) I am sure that what happened was that the scriptwriters needed a childhood trauma in order to set Serac on the course he follows and, in the often grandiose manner of the programme, decide to blow up Paris without any thought as to how that might fit within the world they have otherwise created. After all, as I’ve said, Nolan’s attitude towards time is cavalier at best.

We see that also in the case of Caleb. There is a question about why Dolores brings Caleb into her circle. She has made a point of surrounding herself with hosts that have been implanted with copies of her own pearl (Hale, Connells (Tommy Flanagan)), and given that Connells heads up a team of professional hard men there doesn’t seem to be any particular reason to link up with Caleb. And given that they are effectively versions of herself, she has more closeness and control over her surrogates. In fact, Hale, busy running Delos Corporation, looking after a family, and trying to fend off a take-over bid by Serac, goes through sufficiently different life experiences that she grows away from Dolores, the one episode in the season that contradicts the underlying theme of the predictability of the individual and therefore the opportunity for corporate control. But this doesn’t become an issue until the Caleb-Dolores relationship is well established.

Dolores reveals that she was the first successful prototype host, all other hosts are effectively descended from her. Early on, the US army used hosts as part of training scenarios for their troops, the only occasion in the entire programme in which the state as such plays any part. Caleb took part in one such training session, and was instrumental in stopping his fellows from raping the hosts they had captured. Dolores was among those hosts, remembers the occasion, and that explains her attachment to Caleb.

It is a flimsy and sentimental reason that comes across as a last minute rationalisation on the part of the scriptwriters, certainly it is out of character for Dolores. And I’m not sure it makes sense temporally, either. The implication is that the use of hosts in military training was something that was done early in the history of the hosts, probably before the parks were fully established. But that would put it long before Caleb could have actually been in the military.

We must remember that Caleb was one of those identified as an outlier by Rehoboam, that is, as one too individualistic to do anything but disrupt the predictions and controls over human behaviour that Rehoboam was introducing. Upon leaving the army, Caleb was used to round up other outliers, which is how he came to learn the truth from his predecessor, Whitman, though those memories were subsequently scrambled by his reconditioning at Serac’s re-education centre. (Westworld is surprisingly full of characters – Bernard, William, James Delos, Caleb – whose memories are scrambled.) At the re-education centre we see innumerable outliers preserved in row after row of cryogenic coffins, a scene eerily and deliberately reminiscent of the warehousing of unused hosts we have seen repeatedly in WW1 and WW2. It is possible, therefore, that Caleb might at one point have spent time in cryogenesis, which could account for the otherwise unwieldy gap in the timeline. But there is no specific reference to this, and by stressing that Caleb was one of the few outliers who was successfully reconditioned, it is implied that he was not frozen.

Thus the two significant characters who are introduced in WW3 both seem to break the timeline of Westworld. This, I think, is not a deliberate part of the mystification of Westworld, but is rather another sign of the generally cavalier approach to time that has been a feature of all three seasons. There is a carelessness in the way the temporal landscape is sketched in from season to season, as if time, continuity, chronology, play little part in the otherwise very deliberate and careful worldbuilding that has gone into the construction of the programme.

And yet, Nolan and Joy and their creative team are not unaware of the dramatic effects of time, as the very last scene of WW3 reveals. As Stubbs lies wounded, Bernard dons a headset he has acquired, and becomes inert. When the camera cuts to him next as he comes back to life, he is covered in such a layer of dust that it is clear some considerable time has passed. Whatever time the fourth season is set in, it will not be the same time as the seasons we have seen so far.

Copyright Paul Kincaid. All rights reserved.

I may be making too much of this but: in the scene where Caleb stops the soldiers raping the hosts, one of the soldiers makes a remark which suggests the parks are active and something people know about: “f*ck that. We just liberated these girls. What is it those rich m*therf*ckers do when they’re here?” and Dolores’ opening remark says the exercise took place in “Delos, Park 5”. So it sounds like that scene did take place later.