By Christy Dena

This piece contains mild spoilers and mild mind scrambling if you haven’t seen the 2018 film Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

Margaret Thatcher had something to say about Miles Morales, so too did narrative theorist Seymour Chatman, as well as those fighting the idea of a “half-black, half-Hispanic” Spider-Man (Rose, 2018). It wouldn’t be a stretch of my tingly senses to say these folks share the belief that there is no alternative, there is a single, right, way. Thankfully, the opening sequence of the film Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (screenplay by Phil Lord and Rodney Rothman, story by Phil Lord), sets the scene for social change with some cool emancipatory narrative devices.

It’s the kind of interventionist work that needs to be done because audiences have been trained to approach their story experiences, and much of life, with closed thinking. As part of his work on The Psychology of Closed Mindedness, social psychologist Arie Kruglanski explains that ‘the need for closure is the desire to have certainty, to have a definite answer to a question and avoid ambiguity’ (Kruglanski, 2021). A consequence of this is we can ‘jump to conclusions about others, and to form impressions based on limited and incomplete evidence’ (Kruglanski, 2004, 2). That character is the killer! Capitalism is the answer!

Former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher found it hard to imagine alternatives, and encouraged everyone else to find it hard. Thatcher is associated with the slogan ‘There is No Alternative’ — which refers to the neoliberal logic she popularised. In a speech, Thatcher not only said ‘there’s no real alternative,’ but also said ‘What’s the alternative? To go on as we were before?’ (Thatcher, 1980). As if the future is a long, single, inevitable, line of progression and the only choice is to stick with what isn’t working or proceed in the only available direction. Do nothing and crumble, or do the only change available.

In Capitalist Realism, Mark Fisher connected the belief that there is no alternative to capitalism with dystopian films and novels that don’t imagine ‘different ways of living’ (Fisher, 2009, 2). Instead of representing or prefiguring different ways of living together, many works of fiction depict the destruction of the world by unbridled capitalism. Even our fiction jumps to conclusions.

Craft discussions nudge the writers’ hand to do this. While those working in narrative structures do sometimes admit there are different ways of designing narratives, they regularly render such alternatives as substandard or corrosive. Twenty years before Robert McKee cemented such language, Seymour Chatman, in his book Story and Discourse, conspicuously framed varieties of narrative design. He spoke of classical narrative as a network of choices ‘only one of which is possible,’ and spoke of the ‘antistory’ as ‘an attack on this convention which treats all choices as equally valid’ (Chatman, 1978, 56). As in, it is normal for the design to have only one viable option, and it is antagonistic to have multiple valid options.

Irrespective of whether the deviations are considered inspirational,1 multiple valid choices don’t have to be framed or perceived as an ‘attack,’ or ‘antistory,’ ‘antinarrative’ (Chatman, 57), ‘unnatural narrative’ (Richardson, 2015), or ‘antiplot’ (McKee, 1999); just like the multiple ways of making games don’t have to render them games or ungames, ‘anti-games’ (Fredner, 2014); and the multiplicity of bodies, minds, and cultures in life as normal or not.

It’s this closed thinking the opening of the film acknowledges. The white male character of Peter Parker (Chris Pine) says, “For ten years, I have been the one, and only, Spider-Man.” He repeats it, saying “the only thing standing between this city and oblivion, is me. And I’m the only Spider-Man.” This notion of there being only one is of course in the popular history of Spider-Man comics, movies, TV shows, and products. Despite the retroactive continuity shifts that are normalised in comics, and the actual variations to Spider-Man in the comics and games, it is this notion that has travelled the furthest. This was the starting point for many in the audience of the film, including me. But, unlike some, I was one of the many who was open to and even yearning for there to be more. The opening design of the film guided all of us to multiplicity.

In his book Narrative and Freedom, literary theorist Gary Morson makes the connection between narrative devices and our perception of possibility. He contrasts the fatalistic nature of foreshadowing with what he and Michael André Bernstein called sideshadowing.2 He says, in ‘contrast to foreshadowing, which projects onto the present a shadow from the future, sideshadowing projects—from the “side”—the shadow of an alternative present. It allows us to see what might have been and therefore changes our view of what is’ (Morson, 1994, 11).

He says sideshadowing helps us think that ‘[t]hings could have been different from the way they were, there were real alternatives to the present we know, and the future admits of various paths.’ And this has ‘profound implications for our understanding of history and of our own lives,’ because among other things, it ‘encourages skepticism about our ability to know the future and the wisdom of projecting straight lines from current trends or values’ (Morson, 1994, 6). There are alternatives. There doesn’t have to be one Spider-Man, or only classical narrative, or racism….3

Even though this emancipatory design work explains what I think the film is doing, Morson is adamant sideshadowing refers to a specific device. With sideshadowing, Morson isn’t referring to some general sense that things could have gone differently. He’s talking about narratives which vividly show the audience what might have happened, but didn’t. When all alternatives are possible, it is not sideshadowing. A sequence in Adam MacKay’s 2018 film Vice is a prime example of this definition. About 40 mins in, Dick Cheney (Christian Bale) is considering the impact him being Vice-President may have on his gay daughter. We then see the Cheney’s leaving politics for the health of their family. The credits roll as they have fun at a family picnic far away from the media and chambers. But then the film takes us back to what Cheney actually did. He went ahead with his Vice-Presidency. This is effective because it shows what could have happened but didn’t. It shows there was always a choice. As sideshadowing, it is an alternative present that wasn’t taken up, a shadow cast over the present from the side.

So, in the spirit of Morson’s language, I’m calling what we’ll talk about the micrologics of sidesetting — where possibility, multiplicity, and optionality is encouraged. These micrologics till the soil so pluralistic thinking can sprout. This means the closed thinking we can all slip into, whether we’re a Thatcherite or a dystopian writer, is nudged out of the way. These devices set the scene for changing our expectations about the story, and potentially, life. This is what film and television researcher Nitzan Ben Shaul talks about in his 2012 book Cinema of Choice. He talks about how movie narrative devices can encourage viewers to reduce or even block their optional thinking (Ben Shaul, 2015, 8),4 or they can encourage it with great pleasure and gratification (Ben Shaul, 2015, 13). ‘There are a small number of movies,’ he says, that ‘open up the mind to thoughts of choice and possibilities’ (Berghahn Books, n.d.).

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse fits what Ben Shaul says about a particular device, that of narrative alternatives to previous works of fiction. Distinct from an alternative history which can promote optional thinking by offering a different path in contrast to what happened in the actual world (I talk about this regarding Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time…, Dena, 2023), these alternatives are contrasted with the fictional world. Ben Shaul gives the example of Luis Buñuels’ film adaptation of Joseph Kessel’s novel Belle de Jour. In our context, it is the alternative to what is commonly associated with the fictional world of Spider-Man. There isn’t just one Spider-Man, now (and for those who were aware since 2011) there is (at least) Miles Morales (Shameik Moore) too! In a world where Spider-Man — through multiple visual appearance, actor, and storyline changes — has predominately been associated with one, white, boy, it breaks the rules.

Indeed, for some, this actual plurality is experienced, à la Chatman, as an attack (Petri, 2011). There cannot be multiple viable diverse characters, only one ideal one! This is why I found all the preparation work that went into introducing this alternative Spider-Man interesting. Beyond the cognitive effect Ben Shaul talks about regarding our expectation of the previous Spider-Man compared to this new one, is what happens in the micrologics of the teasers and the opening sequences of the film. During this time, there are sidesetting devices that quick-unpick closed thinking, and help facilitate or at least normalise pluralism.

It’s not that the creators were deliberately trying to do sidesetting or whatever term you like to describe this design work. Take the first device I’ll talk about: multiple artistic styles. The mix of artforms can be a neat way to communicate the relationship with the comics, may have been a personal interest of the artists involved, as well as a neat visual storytelling and orientation device to depict characters from different dimensions. So the promotion of multiplicity and optional thinking happened because of creative decisions made for a range of reasons.

In 2019, many of us were introduced to these multiple artist styles with the fifteen Spider-Man logos shared in a teaser clip released on social media, and analysed in articles such as the one in Geek Outpost (Tammer, 2019). But for those entering the universe with the film, the opening depicts logos — for Columbia, Marvel, Sony Pictures Animation, Pascal Pictures, and Comics Code — cycling through artistic styles. The mix of artforms prepares us for when we see multiple Spider-People and Spider-Creatures with some of them having their own distinct art-style. As Ben Shaul explains about optional thinking in movies, design devices can ‘lead viewers to construct, entertain, compare, and assess different points of view or optional narrative trajectories out the films audiovisual flow’ (Ben Shaul, 2015, 122). I’m saying the multiple art styles are potentially doing this as well. Especially in the context of how we’ve learnt to find pleasure in the familiar. In our world, where mono-disciplinarity is equated with mastery and brand integrity, this cross-artform treatment rambunctiously stokes the desire for multiplicity and difference.

Then there is the use of split screen — which can also be inspired by and speaking to the comic origins of the story. But it also, especially when combined with all these design decisions, contributes to this stoking of multiplicity. We’ve got times and spaces being the subject in the story (with characters talking about parallel universes and the actual multiverse that happens), and so these are represented visually, but they are also a visual representation of a pluralistic notion of the world. Not just the storyworld, but also the multifarious nature of the actual world. For instance, my inner life is not specific to the time and space in front of me, so I’m totally fine with that truth being normalised. When I walk down the street, if I hear a bird that captivated me as a kid, then I also have playing in my mind walking along the park to school and hearing that bird. When I hear a dance track I used to rave to, the smell of powder (to put on the dancefloor) is there, flashes of conversations, and what I was wearing. When I feel alone in the world, I hear my passed mum speaking to me. There are different ways to creatively represent and experience the world. So maybe these devices are in fact renaturalising narrative rather than attacking it?

The screenwriters also prepare the audience for the dimensional storyline and the co-presence of multiple Spider-People, with multiplicity and possibility dialogue seeded throughout the first ten minutes and onwards. For instance, a journalist in the background mentions “multiple seismic events.” There is a class, where “parallel universes” are discussed, along with the idea that “time is relative.” It is also threaded through character dialogue about family members who “had a choice,” and joking to the son about how “you don’t have a choice,” and the son, Miles, repeating the play with “I choose to.” This kind of language is part of the greater superhero and individualist narrative, and is a device writers employ more generally, but with all of these other elements it aids in bringing potentiality to the table. Unlike Thatcher’s, Chatman’s, and Cheney’s overinvestment in a single course of action, Miles, and us, are being encouraged to consider more. It’s a word cloud drifting through us and setting the scene for what Ben Shaul describes as ‘the pleasurable arousal of viable optional thinking.’

It’s not that the seeding of such language automatically promotes optional thinking, but I personally have found it contributes to the cumulative effect. This language is also not necessary for multiplicity to be cued either. Elsewhere, I’ve spoken about the role of Quentin Tarantino’s certainty dialogue in promoting closed thinking as a way to enhance the optional thinking surprise at the end of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood (Dena, 2023). Either way, since I’ve noticed this language seeding device, I’ve been utilising both in my own fiction and nonfiction writing to (I believe) great effect. We don’t always pay attention to it, but our wordbuilding can kindle different relationships with the world.

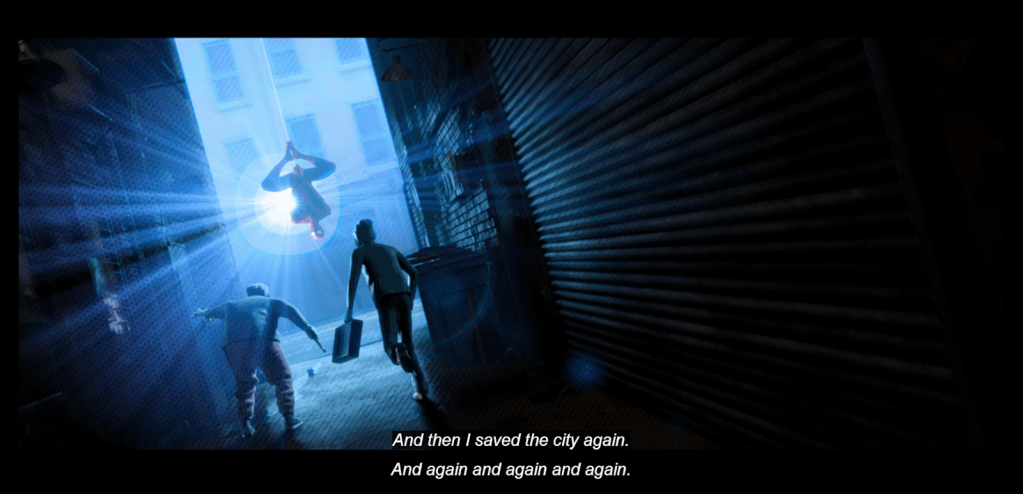

Then there is also the use of repetition with difference. We opened the film with Peter Parker introducing himself, and talking about how he repeatedly saves the city, over and over again. He opens his monologue saying, “All right, let’s do this one last time…” Which is true for this Peter, because he does die in this film. It is also playful because it is not the last time these words are said (or will be). And this playful multiplicity is derived from a sentence that is remarkable for its sense of closure: we’ve been here before, we know what’s going to happen, there is nothing new here. Significantly, then, this same introduction formula is repeated when we come across another Spider-Man: Peter B. Parker (Jake Johnson). He says, “All right, people, let’s do this one last time,” and we see his comic cover and hear the monologue play out. It happens when we meet Gwen Parker (Hailee Steinfeld), and she says, “All right people, let’s start at the beginning one last time.” The monologue continues with Spider-Man Noir (Nicolas Cage), Peni Parker (Kimiko Glenn), Spider-Ham (John Mulaney), and Miles Morales when he takes on his identity. Each with their own take.

Ben Shaul talks about how the relationships between artworks can ‘[c]ompel viewers to compare the new work in respect of the original it subverts, while also realizing the viable alternate offered’ (Ben Shaul, 2015, 142). We’re getting this within the film too: with each new comic cover and monologue. Now, I remember my first viewing and how compelling it felt. Like it was taking a formula and doing something that shouldn’t be allowed, and then doing it again, and again. Kinda naughty. Definitely exciting.

It’s not that all these devices facilitate optional thinking in everyone, will always work this way in every design context, and aren’t able to be used for oppressive aims. I feel they work here because they fit with the underlying logic of the storyworld, and because of the greater context of how Spider-Man, classical narrative, and artforms are perceived. In this film, these micrologics work together to help us feel comfortable with the big shifts happening within the story, with Spider-Man, with storytelling in general and the notion of a single hero, and, I contend, with pluralism in life. Not just comfortable, but it makes sense, and is gratifying. When our minds click through the multiplicities on offer, we get to rethink our relationship with possibility. So much so that when folks come along and insist ‘There Is No Alternative,’ we know it’s not true. There is always more possible.

Indeed, there is Insomniac Games’ Spider-Man: Miles Morales, which is another conversation. And the trailer of the next film teases a similar investment with Miles struggling to move beyond a limited one or the other choice (Sony Pictures, 2023). Whatever direction it goes, though, we’ve had this experience and they’ll be more in many other worlds too. In the end, it doesn’t matter if the design involves classical or so-called anti-story or anti-game elements, as none of this matters if the creatives, audiences, and players are emancipated. The social scene has already been (side)set.

FOOTNOTES

- It is important to note that the works employing such deviations are (for Chatman and many other formalists) viewed positively. Chatman says Jorge Luis Borges ‘beautifully described’ the ‘logic of this kind of antistory,’ and refers to the ‘spectacular novels’ of Alain Robbe-Grillet, who exemplifies ‘another kind of antistory.’ Chatman, Story and Discourse, 56-57. I have invoked the term ‘inspirational’ to describe this, to draw a parallel between how disability can be regarded as inspirational and an aberration at the same time. The notion of ‘inspiration porn’ was introduced or popularised by Young, ‘I’m not your inspiration, thank you very much.’

- Morson talks about how foreshadowing works as ‘consequence of events to come. Foreshadowing,’ he continues, ‘involves backward causation, which means that, in one way or another, the future must already be there, must somehow already exist substantially enough to send signs backward. Thus, if a writer should believe in fatalism, foreshadowing is an ideal way to convey this sense of time.’ Morson, Narrative and Freedom, 7.

- Racism is of course a recent invention in the last two thousand years. It doesn’t have to be. See Painter, The History of White People.

- Drawing on Kruglanski’s work, Ben Shaul explains how the need for closure ‘leads individuals to seek closure by “seizing” upon scant available data and readily available previous knowledge, and to cognitively “freeze” upon hastily forced conclusion that affords the desired closure.’ Ben Shaul, 8. For example, Ben Shaul talks about the narrative strategy of a twist, and in particular the interplay between cataphora (early cues/foreshadowing) and anaphora (the later recall of these clues). Even though we’re given clues to the truth throughout a story, the design encourages us to dismiss these pieces of information because we seize on other information. Or, to put it another way: a red herring only works if we seize on scant data and freeze on a conclusion. The design relies on closed thinking to facilitate suspense and surprise.

REFERENCES

Ben Shaul, Nitzan (2015 [2012]) Cinema of Choice: Optional Thinking and Narrative Movies, New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Berghahn Books (n.d.) Cinema of Choice, Berghahn Books, https://www.berghahnbooks.com/title/BenShaulCinema.

Chatman, Seymour (1978) Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Dena, Christy (2023) ‘Once Upon An Alternate World,’ Issue 19, March, After the Art, https://aftertheart.com/2023/03/28/once-upon-an-alternate-world/.

Fisher, Mark (2009) Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, United Kingdom: Zer0 Books.

Fredner, Erik (2014) ‘The Year in Anti-Games,’ Kill Screen, 18 Dec

Kruglanski, Arie (2004) The Psychology of Closed Mindedness, New York, Oxon: Psychology Press/Taylor and Francis Group.

Kruglanksi, Arie (2021) ‘The Annual College Forum: Stumbling Towards Creativity – Overcoming Our Closed Minds,’ presented at University of Maryland on 26th March, published on Maryland Arts and Humanities 4th May, https://youtu.be/FMUuFdWKxjk.

McKee, Robert (1999) Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting, London: Methuen Publishing.

Morson, Gary Saul (1994) Narrative and Freedom: The Shadows of Time, New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Painter, Nell Irvin (2010) The History of White People, New York, London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Petri, Alexander (2011) ‘Sorry, Peter Parker. The response to the black Spiderman shows why we need one,’ The Washington Post, 3rd August, https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/compost/post/sorry-peter-parker-the-response-to-the-black-spiderman-shows-why-we-need-one/2011/08/03/gIQAViObsI_blog.html.

Richardson, Brian (2015) Unnatural Narrative: Theory, History, and Practice, Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press.

Rose, Steve (2018) ‘Move Over Spider-Man, the New Spider-Man Ushers in a Bold New Superhero Era,’ The Guardian, 7th Dec, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/dec/07/move-over-peter-parker-the-new-spider-man-ushers-in-a-bold-superhero-era.

Sony Pictures Entertainment (2023) ‘Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse – Official Trailer #2,’ Youtube, 4th April, https://youtu.be/shW9i6k8cB0.

Tammer, Marc (2019) ‘Spider-Verse 2 Swings into Theatres in 2022: 15 possible new spider-people hinted at,’ Geek Outpost, 7th Nov, https://geekoutpost.com/spider-verse-2-logos/.

Thatcher, Margaret (1980) ‘Speech to Conservative Women’s Conference,’ 21st May, Festival Hall, Margaret Thatcher Foundation, https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/104368.

Young, Stella (2014) ‘I’m not your inspiration, thank you very much,’ TEDXSydney, https://www.ted.com/talks/stella_young_i_m_not_your_inspiration_thank_you_very_much.