Paul Minott worked as a leading graphic designer for over thirty years, working for

numerous international design consultancies in London and abroad. He ran a

successful partnership in London before embarking on a teaching career at Bath Spa University. He now works making one-off abstract prints using an etching press.

James Gillham completed a practice-led Ph.D. in Fine Art at the University of Reading in 2014, researching capability via the intersection of institutional demands and intersubjective expectation. He continues this research by painting the Humpty character from Olaf Stapledon’s Last Men in London, and by seeking similar representations in Science Fiction. James lives and works in Wiltshire, and is the cover artist for the latest issue (299) of Vector.

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915–23. VIA CREATIVE COMMONS/COURTESY PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART

Marcel Duchamp’s famous work The Large Glass (1915-23) has been duplicated numerous times, by artists such as Richard Hamilton (1965) and Ulf Linde (1961). Duchamp’s approval of these pieces emerges from his established interest in the ready-made, but also points to a more nuanced conception of time situated in popular contemporary European Modernist thought.

Nude Descending a Staircase, No 2 (1912) is perhaps the most explicit example of this interest with temporality, but the glass mechanisms such as Rotary Demisphere (Precision Optics) (1925) bring these engagements into clearer focus. These spinning devices suggest an investigational approach to time’s passage – expansions and contractions operating between objective measurement and subjective experience.

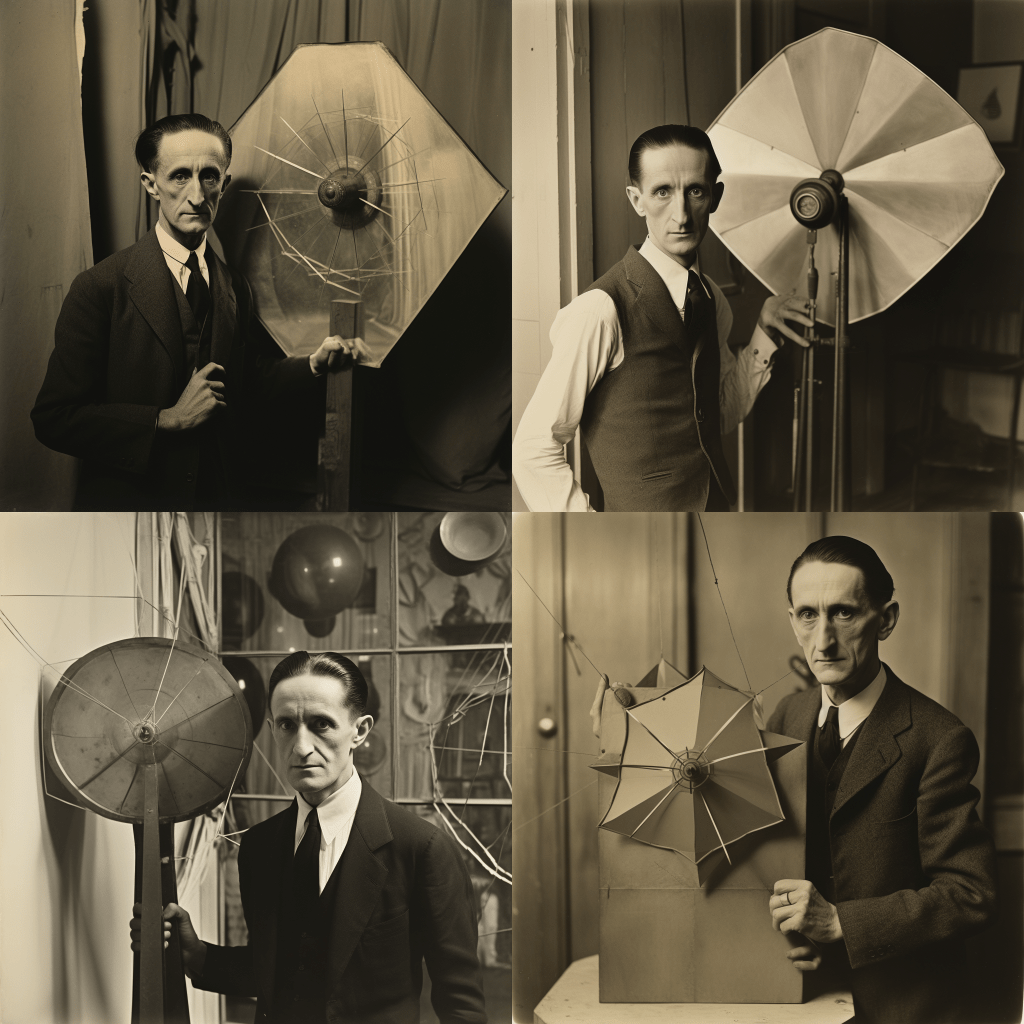

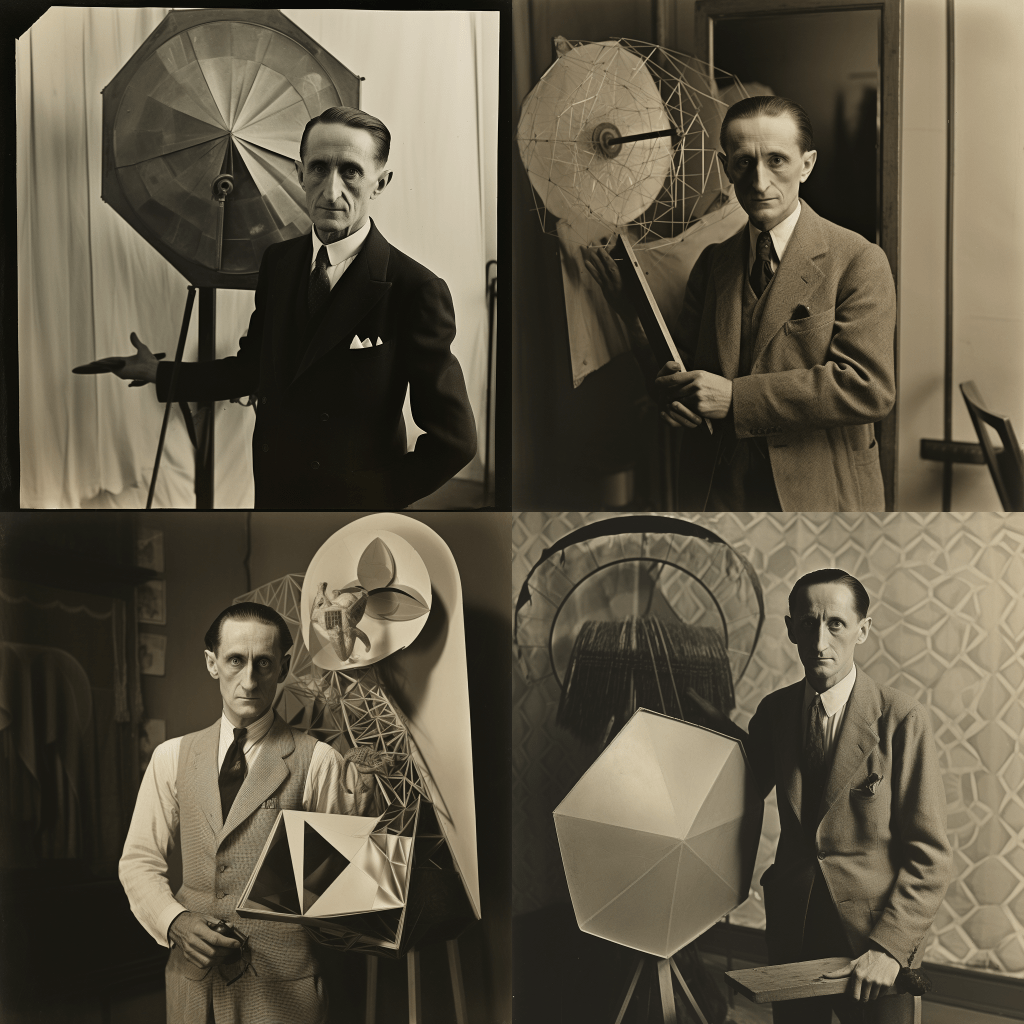

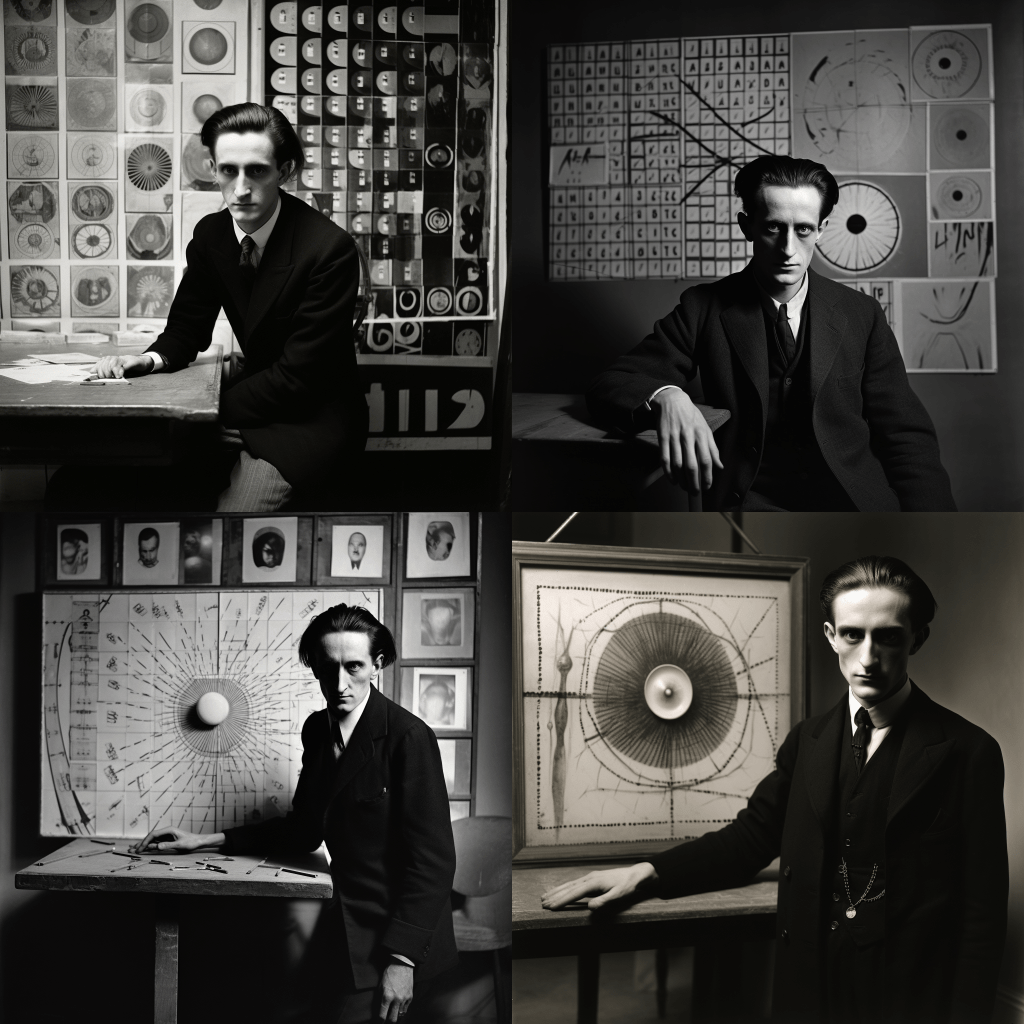

Duchamp’s ludic approach to time has interested artist and printmaker Paul Minott for many years, and is the impulse behind Minott’s latest work: Portrait de Voyage dans le Temps. Portrait de Voyage dans le Temps is an Artificially Generated visual essay, showing Marcel Duchamp alongside his various time machines.

Minott discusses Duchamp’s Modernist conception of time and how this appeared in Duchamp’s artwork – while finding parallels with contemporary use of Artificial Intelligence to generate images – with fellow artist James Gillham.

James Gillham – Tell me about this new work, Portrait de Voyage dans le Temps. It’s different to your current printmaking, what prompted you to make it?

Paul Minott – I’m not sure if it’s a ‘work’ exactly; the entire sequence of images was made with Midjourney in the space of about 10 minutes. What might be done with them, if anything, remains to be seen. Like Duchamp, I’m prepared to wait, to let ‘dust breed’ as it were. My son had made a sequence of images with a prompt describing an imagined photograph of two dodgy blokes in a dingy pub. His first prompt was a deliberate mistake, in that he asked for a ‘1600s photograph’.

What returned was a jovial tavern scene resembling a Dutch genre painting, but as a sepia photograph, or perhaps a Daguerreotype. Midjourney had synthesised time and medium to create an illusion of an impossible photograph. By simply changing just the date, each subsequent iteration returned a convincing photographic ‘look’ for each decade. The two blokes carried a resemblance across the sequence, while everything else changed. It was like a multi-generational story.

So I figured I’d put Midjourney’s photographic ‘knowledge’ to the test, and asked it to recreate a real historic photograph with a minimal prompt. I’d always been struck by a photo Man Ray took of Duchamp in 1920 where Duchamp is standing behind his Rotary Glass Plates as its glass blades spin. The spinning blades had the effect of blurring out the figure behind, and Duchamp became a ghost…or a time traveller. So I idly wrote the prompt:

/imagine: Photograph by Man Ray of Marcel Duchamp standing beside a Readymade

and was astonished by what came back. A dapper gent, with some resemblance to Duchamp’s deadpan expression, holding four variants of a contraption that could only be informed by his Rotary Glass Plates, even though I’d not suggested this. What did this AI thing know? I wondered. I submitted the same prompt again, and back came another set, remarkably consistent with the first. Thinking back to the original scene, I remembered there was a Cyrillic eye chart pinned to the wall. So I added ‘optical charts’ to the next prompt and asked for a younger, and then an older Duchamp. The younger set gave me possible doubles of Dalí and Buñuel, while the older set captures Duchamp’s brooding, hermetic quality.

JG – It seems that he was interested in time and space. Duchamp’s most famous painting is Nude Descending Staircase (1912); these pieces propose a sort of simultaneity?

PM – Well, I think time was certainly in the work. If you think about the rotary pieces there is a sense of perpetual motion, and as they spin, there’s a sense of depth through a kind of peculiar optical illusion. I think he was very in tune with the idea of going slow and going fast. He spends a long time manifesting work, for example, The Large Glass (1915-23). It takes him about 15 years to work on it, only to then abandon it. The working title he gives to The Large Glass is a Delay in Glass. So, there’s this idea that things are not necessarily made for this moment, but for some other moment.

JG – The Large Glass was of course replicated by Richard Hamilton in the 60s. And Hamilton, through the Independent Group, had a link with Paolozzi who leads us back to New Worlds magazine, Ballard, and others. There seemed to be a lot of activity during this time that brings together Modernist Science Fiction and the Modernism associated with the Visual Arts. Do you think this ‘call back’ to Duchamp by Hamilton and others is as important as it appears?

PM – It’s tempting to think that Hamilton was ‘looking backwards’ by replicating The Large Glass, but this was really a technical exercise and the centrepiece of the 1966 Duchamp retrospective which Hamilton was organising at the Tate. While very elderly at this point, Duchamp had been ‘rediscovered’ by young American artists by virtue of his first (!) retrospective in California in 1963. And so in a sense, Duchamp was suddenly a ‘contemporary artist’ because his ironic detachment struck a chord with an emergent sense of ‘cool’. This ‘cool’ acquired the moniker of Pop, a self-conscious rejection of forties/fifties abstraction with its existential pretensions and painterly concerns. Hamilton himself defined this new sensibility:

‘Popular, Transient, Expendable, Low cost, Mass produced, Young, Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, Big Business.’

It strikes me that this list might be an apt description of the trajectory SF has taken from its pulp, low-brow status in the early fifties to the dominant cultural influence it is today. My understanding also, is that New Worlds (under Moorcock’s editorship) represented a similar break with earlier SF writing: it became cooler, more ironic, more tentative and speculative…and like Hamilton, took a ‘British’ turn, more introspective. Ballard’s ‘inner space’: an intersection between eros, thanatos, mass media, and technology, seems pertinent to both fields, especially by the mid-sixties.

JG – When we think of Modernism we tend to think of a speeding up of time, using mechanisms to speed things along. Duchamp travelled across America, and indeed from Europe to the US.

PM – Yes! Seven times I think he crosses the Atlantic, sometimes at the most perilous times. One interesting thing about Duchamp in relation to his Readymades is not so much what they looked like. He would choose things that were as aesthetically insignificant as possible, trying to evade any notions of ‘taste’. So I think he was more interested in choosing something that had no aesthetic value or significance at all, but given the right time and place – the situation – would acquire a sense of significance. So in a way, using a prompt in AI is rather like a Readymade in that a simple set of instructions or descriptions might become for example a snow-shovel hanging from the ceiling (In Advance of a Broken Arm (1915)). So in other words, the titles of his Readymades are almost like prophecies, like a description of something yet to happen. At some point, at some moment in time, this particular thing will happen. And in a way the words are the art as much as anything else is.

JG – So it’s coming together of time and space. I’m reminded of that bit at the start of M.P. Shiel’s The Purple Cloud (1901) when under hypnosis, a person is able to travel not just in space through astral projection, but also through time. And I suppose it might tap into the climate of scientific discovery of the time. I suppose Duchamp would have been feeding off that?

PM – Well, I think he was, especially the ideas of Henri Poincaré and non-Euclidean space. Duchamp in his early years talked a lot about the fourth dimension. Later on, he comes up with the notion of the infra thin, which is a strange kind of subtle distinction, if you like, between one condition and another condition. Much has been said of The Large Glass as being a kind of slice through four-dimensional time, which brings to mind Edwin Abbott’s Flatland (1884) which became popular in the 1920s, exactly that moment where those kinds of ideas about dimensionality are coming to the forefront. Duchamp was a child of the late Victorian period, born in 1887. So certainly, there was stuff in the air, the emergence of what came to be known as the New Physics. Towards the end of his life, Duchamp reacquainted with Salvador Dalí, both spending their summers in Cadaques, Spain. Dalí was similarly fascinated by quantum mechanics, as it was understood at the time. So I think the elasticity of time was always kind of a thread that runs through Duchamp’s life.

JG – What are the parallels between Duchamp and the contemporary use of Artificial Intelligence to generate images – would he have approved, do you think?

PM – Less concerned with the merely ‘optical’, Duchamp used playful homophonic language as a generator of images which could be quite mechanical in their execution. The titles of many of his works read like predictions of forthcoming events (rendezvous in his terms): a snow shovel will one day hang from the ceiling in advance of the broken arm. It’s nonsense, and yet a kind of ‘anartistic’ intelligence could create something from such a cryptic clue. His works were propositions that, at one time and one place, happen to have that appearance, but there’s the sense that

Given:

1. the right time, and

2. the right place

a completely different image might emerge.

His all important signature was never a signifier of ownership or authorship, so much as one of a detached witness. His father, like da Vinci’s, was a notary. Ultimately, it mattered little by whom his work was made. It’s the titles that do the work. To quote a later conceptual artist, Sol LeWitt, the idea is the machine that generates the art. It seems to me that this way of using words in AI to generate images is the direct descendant of Conceptualism. One could enter the same instruction, time after time, and within minutes receive a different visual outcome, always rendered with a high degree of plausibility. And it wouldn’t matter who writes the words.

In a sense, the physical Readymade is as it were the ‘instant, pop-up outcome of an algorithm’; an object simply hanging in time and space, just one of an infinite number of possibilities. Random, meaningless and yet strangely beautiful and self-conscious. AI art one might argue is a Readymade generator.

I think Duchamp might’ve regarded AI as the vindication of his ‘anartistic’ ideas about originality, creativity, and posterity.

JG – Is there a connection between Duchamp’s interest in the Readymade, and AI? Or perhaps more so the selection of randomised contrivances by the artist like in The Large Glass?

PM – Yes. The Large Glass is a synthesis of bizarre processes, a slice through four dimensional space, as if captured in a split second onto photographic glass. It makes no visual sense to us because we exist in a plane which can’t conceive this dimension. Or one might think of his Three Standard Stoppages (1913-14) whereby three identical lengths of string were dropped from a given height, and how they fell became the basis for other works. The idea that planned chance and coincidence could create a new kind of art is exactly where we are with this.

In 1957 he gave a lecture entitled The Creative Act, one thrust of which was that time itself was the only arbiter of value for works of art, and that half a century would have to pass before any work might achieve significance. He was clearly alluding to his own, belated reputation, and it certainly became true in his case. I think at some point he also said that his use of time was his greatest contribution to art. The best biography of Duchamp is the Ephemerides accompanying his retrospective in Venice in 1993, whereby his entire life is set out in time travelling fragments: Tuesday Ist March 1960 followed by Monday 2nd March 1936 etc. He was constantly in motion, travelling very light, unencumbered. I think in this sense his conception of time was Modernist: fragmented, peripatetic, coincidental, distended.

I once playfully imagined that The Large Glass was some kind of time-travel machine. He worked on it for years, abandoned it (‘definitively unfinished’), exhibited it briefly in Brooklyn after which it accidentally broke. After a long delay, he decides to painstakingly repair it, relishing every crack, and finally has it installed (forever!) in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in a room dedicated entirely to himself. A note that he writes in 1913 in preparation for The Large Glass becomes the title of an installation he begins 30 years later. He then spends a further 20 years building this in secret, and prior to his death, leaves detailed instructions for its final installation in the same room as The Large Glass. And then there’s all those suitcases (Boîtes en valises): surely every time traveller needs a suitcase? But to make 300 of them (some posthumously!) over decades suggests multiple, perhaps simultaneous, destinations.

These sixteen images of alternative Duchamps, in different settings with different imaginary objects, evoking different moments in time, yet all made within 10 minutes and remarkably consistent seem to me appropriate somehow. A single verbal prompt at one point in time (like the title of a Readymade) can generate a series of alternate but equally viable ‘realities’ across time.

JG – So the generation of the images or Portrait de Voyage dans le Temps through artificial intelligence is akin to a Readymade in some way, in that a Readymade is already there and it’s being positioned by the artist in a certain place? Is that the same sort of process with the MidJourney AI system?

PM – Where I’ve been using it myself, rather than use verbal prompts I’ve been asking it to blend simple geometry to see whether it can create new shapes which I wouldn’t ordinarily conceive. I find that fairly quickly you’re in dialogue with this thing and you ask yourself, ‘is it creating the image or am I creating the image’?

There are some wonderful examples of people doing this very, very seriously – incredible, clever, complex use of prompts. So all kinds of technical prompts are being used, photographic and cinematic language, mis-en-scene instructions. There are certain artists who are using AI to generate remarkably carefully well-crafted images. I can’t believe that they are not the artists in that respect. What’s extraordinary about Midjourney is that it provides images that are so convincingly real in many forms – so it might be real Manga, it might be real photography, might be real 1940s illustration, real Norman Rockwell. What’s powerful is the fact that it renders things, at least at first glance, so convincingly real in and of itself, and it does it so fast. That’s where it becomes difficult to say, who is creating this? Two people could put in exactly the same prompt, at the very same time and it’ll generate two very different outcomes. And this seems to me akin to a kind of Multiverse. Given the same circumstances this particular cocktail of ingredients could generate one or another form of life.

JG – So in a way AI moves the computer away from the objective thinking machine to the subjective feeling machine – because it brings into focus something which is subjective only to itself and to others, rather than the standard view of the logical single reality. In Modernism, perhaps in both experimental literary Modernism and artistic Modernism, there’s a tendency toward subjective truth pushed up against scientific truths – which I wonder if AI warps a bit?

A bit like in C. S. Lewis’ Out of the Silent Planet (1937) where Ransom finds a monolith, which details the history of the planet he’s stranded on, Malacandra. And similarly in H.P. Lovecraft’s ‘At the Mountains of Madness’ (1936), where the explorers of the Antarctic find a kind of fresco that describes in picture format the history of their culture. The reason those people see the frescoes and think they’re truthful is because they accept on face value that the stories they’re telling through pictorial language are true. And they just accept that it’s true. Whereas I think now we’re much more sceptical in the post-truth world of the truth behind an image.

PM – Yes, one thinks of Plato’s allegory of the cave.

JG – So these images are like an alternate history – like, for example, The Man in the High Castle (1962)? Darko Suvin talks about alternate history novels starting in the Victorian era. I wonder about these Duchamp images and what we perceive as a true image – because these images do look like the real photographs of Duchamp in front of his own artwork. I’m reminded of the photograph in Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five (1969) – a pornographic photograph of a woman with a pony. There’s the idea that a photograph has some sort of residual truth about it, which these photos that you’ve created with AI have that sense of truth about them. In an excellently plural way, and in a way that mirrors what you’ve been saying, that same pornographic photo also crops up in Philip K. Dick’s Flow My Tears the Policeman Said (1974). So even though fictional, like the pornographic pony photos, these AI images feel real. They feel true.

Given that Portrait de Voyage dans le Temps could be considered as an alternate history, what do you think Duchamp, or even the Duchamp of these pictures, would have thought about AI generated images?

PM – One gets the sense that Duchamp only did those things which amused him, and he frequently insisted that deep down he was very lazy, or at least only partially ‘engaged’. So I think this thing which enables anyone to make funny images, using just wordplay and no other ‘artistic’ skill, with a minimum of effort, would’ve been ‘ameusement’ to him. I think one of the key drivers in the popularity of AI is its facility at generating humorous (or at least absurd) verbal and visual outcomes. Surprise and humour are not things we generally associate with ‘serious’ art, but it was a central concern for him (and others such as Alfred Jarry and Raymond Roussel) who sought to puncture the seriousness of ‘art’. I think this is an important quality of much Modernist art and literature which is often overlooked. In this sense, AI has a Dada spirit of which he would’ve approved.

I read recently a description of AI by one of its proponents which was that it was akin to ‘making sand think’. In the same vein as ‘letting dust breed’, I can’t think of anything more Duchampian. And finally, Duchamp’s own epitaph reads ‘D’ailleurs, c’est toujours les autres qui meurent’ (Besides, it’s always the others who die)…so these images, which imagine him still living in other speculative realities seem very fitting indeed.

References:

Duchamp’s Studio at 246 W. 73rd St., NYC, by Man Ray

https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/83334

From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy (Box in a Valise)

https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/89071

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass)

https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/54149

Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2)

https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/51449

Étant donnés

https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/65633

In Advance of the Broken Arm

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/105050