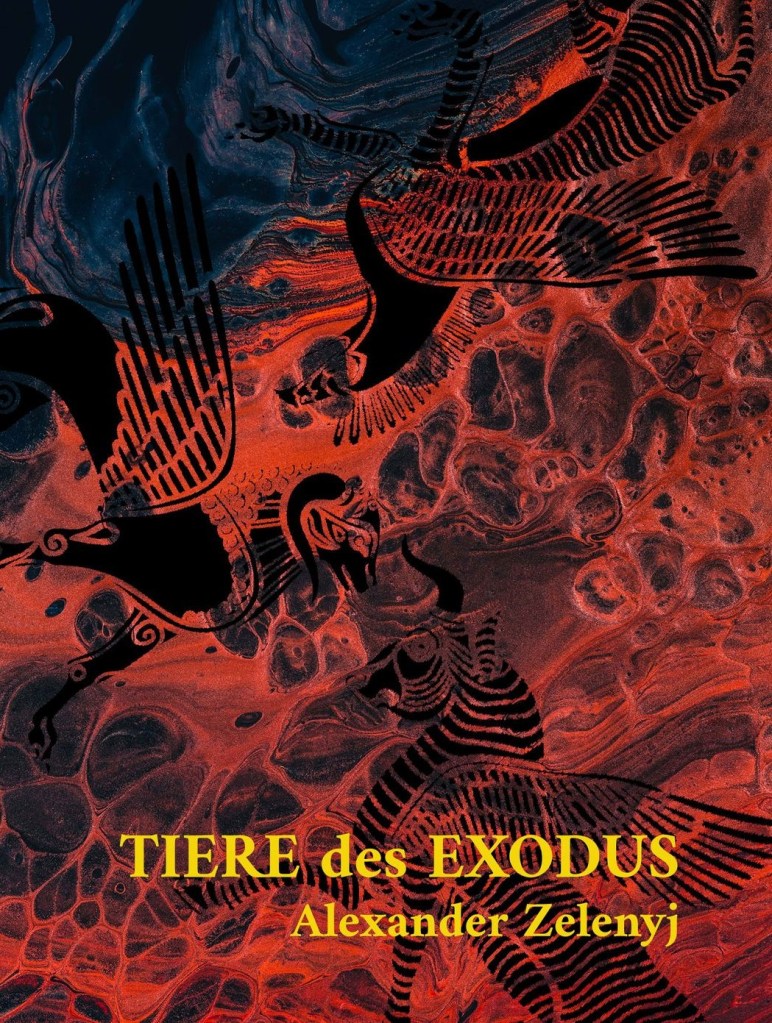

Alexander Zelenyj is the author of the books Blacker Against the Deep Dark, Songs for the Lost, Experiments at 3 Billion A.M., Black Sunshine, and others. His most recent book is These Long Teeth of the Night: The Best Short Stories 1999-2019. His books and stories have been translated into several languages, including German, French, Romanian, Italian, Spanish, and Ukrainian. He has a collection of brand new stories forthcoming from Eibonvale Press in Fall 2024.

Zelenyj lives in Windsor, Ontario, Canada with his wife and their growing menagerie of animals. Visit him online at alexanderzelenyj.com.

David Rix: Thank you for taking the time to talk! How are you finding this new year so far?

Alexander Zelenyj: My pleasure, thanks! I’m finding the year so far very busy. Busy with mostly good things. We have a new kitten and she’s a handful. She adopted us. Showed up at our back porch door on a cold night, tiny and frail. How could we turn her away?

DR: I feel we may need some kind of ‘cat tax’ here – that would definitely get all this off to a good start! But anyway – I have been involved with your writing in various ways for quite a long time now and I have published several of your books, so this is a good chance to dig in a bit and explore what is going on – what makes you tick, as it were.

When reading your stories, one gets the feeling of a lot of different threads coming together, from nostalgia for classic forms of writing to the much more surreal and experimental. Can you tell us a bit about the influences that came together to make you? And maybe which ones came first and which were added later?

AZ: My home library tells the story most clearly, I suppose because I’ve always bought a lot of books and rarely get rid of them. This means I still have all the ones I had when I was a young boy, certain of which had the most profound influence on me. I was most drawn to the stranger books, which turned out to be a lot of science fiction, fantasy and horror. Those genres and many key works from each became foundational influences for me. Especially authors like Robert E. Howard, who has stood the test of time, still has a primal power and weaves a very strong spell. I remember reading Howard’s story, “The Tower of the Elephant” as a boy and having a true moment of clarity—one of just three such moments I’ve ever had in my life—and understanding that I’d just discovered something magical and very powerful, something that called to me in such a strong way that I knew I had to write stories, too.

Authors like Arthur Machen, Ray Bradbury, Edgar Allan Poe, Richard Matheson, and James Tiptree Jr. also had a huge impact on me, and continue to do so. Harlan Ellison as well. His The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World was a revelation for me. All of his collections are amazing but this one has a huge amount of variety between its covers that I’m not sure he matched anywhere else, and it’s some of his most original work. The novella “A Boy and his Dog” does a wonderful job of establishing the lead character’s amoral motivations within a post-apocalyptic wasteland, which turns out to be the most disturbing aspect to the story because it asks (and answers) the question with a kind of unerring logic: how far away are we from being this boy, in this world?

Going back even further, I have an early memory of my mother reading to me from a book of Czech fairy tales by Karel Jaromír Erben. One story in particular, called “Otesánek”, really frightened me—it was about a couple who cares for a baby that has come to life from an inanimate piece of wood.

DR: Yes, people might be more familiar with this story from the film by Jan Švankmajer – Little Otik. That had quite an effect on me as well.

AZ: Yes, that’s the one. The baby’s appetite soon becomes much more voracious than its adoptive parents could have foreseen. Looking back on it, I see a deep pathos to this story about a childless couple wanting so desperately to have a baby that, through some magical means, the universe seemingly grants them their wish, only to have their dreams turn into this deeply disturbing, nightmarish scenario. I still have my childhood copy of the book, and it has a special place on my shelves. This might have been one of my earliest exposures to the supernatural, or the unknowable.

We could talk all day about the many great writers and books out there.

Gene Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun – the canvas is limitless, and what he does on it!

Nova by Samuel R. Delaney—the language is so great. It’s like Beat fiction but comprehensible and so much more inventive.

2666 by Roberto Bolaño, which has a dedicated relentlessness to its horrors that, by the end, left me wishing the world was a better and safer place.

J. G. Ballard’s Crash—such a horrific vision here, masquerading as ecstasy to its cult of death-seeking characters. Speaking of bold visions, this one’s tough to beat. A mechanistic erotic apocalypse in chrome!

Or a classic like Riddley Walker by Russel Hoban, which rewrites the language in the service of the story.

Or Guy Gavriel Kay—sentence for sentence, one of the best writers I’ve read. Just beautiful prose. Take your pick from his substantial catalogue. It’s all worth reading. And a fellow Canadian. Then there is Christopher Priest, M. John Harrison, Ursula K. Le Guin…

DR: Riddley Walker is an interesting one since it’s one of the more genre-straddling works you’ve mentioned. Very much post-apocalyptic but also often seen as more ‘literary’ or ‘experimental’, with a direct link for me to some of the post-modern novels at that time. For me, it highlights just how hazy the boundaries between genres/styles can be – and of course, this feels very much a characteristic of your own work.

It seems fair to say that you cut your teeth, as it were, on speculative fiction, horror, etc. but can you tell me a bit about the other genres that are especially important to you and the development of your writing?

AZ: In my early twenties, I became curious about other literature and started exploring everything from classics to current/modern works. I was always drawn to a lot of darker writing, and found myself inevitably consuming a lot of transgressive literature along the way. A few writers from a more so-called literary (I hate the term when it differentiates itself from genre fiction, which is just as literary and in many cases more complex than so-called literary fiction) area, or realistic schools, also made a big impression on me when I was growing up. Darcy Steinke was important for me. Especially Jesus Saves. She’s written some incredibly dark and disturbing stuff, and I’ve always felt a kinship with some of the difficulties certain of her characters have experienced. Tim O’Brien is fantastic—his novel The Things They Carried, based on his experiences in the Vietnam War, is excellent. And Davis Grubb’s Night of the Hunter, which is one of my favourite novels. Every sentence is a jewel. Southern gothic fiction at its finest. And it holds a kind of terror that’s tough to find in fiction. Raymond Carver’s stories are amazing—his “Tell the Women we’re Going” is probably the most frightening story I’ve ever read.

But inspirational works abound, I’m discovering new ones all the time. The most recent book that really moved me was by a French writer named Gabrielle Wittkop, a collection of stories/novellas entitled Exemplary Departures. It’s absolutely incredible. The stories are a great synthesis between powerful, engaging storytelling and eloquent prose-craft. A very dark and disturbing collection, but with moments of breathtaking beauty throughout. It has that powerful mix of the grotesque and the beautiful. Her story “Idalia on the Tower” is a masterpiece. (What is it about stories featuring towers as their centrepieces that’s so evocative? Is it the suggestion of trying to climb toward the unknowable Heavens, to grasp some greater meaning that lies above our mundane mortal existence? Saying this makes me realize that I also wrote a story with a similar theme/idea, published in my last book.)

In recent years I’ve started exploring crime fiction, as well, and for a while became obsessed with Jim Thompson. I’d heard about him for years and I’m happy I sought him out. Very minimalist, readable stuff, snappy dialogue, and extremely dark plots, with casts of unlikeable characters with little to no redeeming qualities—and yet in the end I find myself rooting for the protagonists (most of them anyway). It’s some kind of literary genius to be able to craft such despicable characters and make the reader understand and sympathize with them. I don’t tend to read multiple books in a row by the same author (unless I’m reading a series) but with JT I couldn’t help myself and read a dozen novels in a row before needing to rise up through the pulpy grime for some air. But I’ve been back in that underworld since and it’s an exhilarating and addictive place he creates.

Another recent discovery for me was Paco Ignatius Taibo II, a Mexican writer known for, among other things, a series of novels featuring a one-eyed detective named Héctor Belascoarán Shayne. The unique spin on the series is that the fourth novel concludes with the protagonist being shot to death, only to be resurrected without explanation in the following book. I love that added air of mystery, the unsubtle merging of detective story with outright fantasy. And it isn’t ignored in the subsequent book; in fact, the protagonist is greatly affected by his own death and resurrection—but no explanation is ever provided. And that’s great! There are too many books and films with unsatisfactory explanations. It seems modern audiences need to have all the loose ends tied up in a narrative or they won’t feel satisfaction. Which I find strange since all too often the ultimate explanation or reveal is incredibly disappointing, and predictable, and uninspired. Give me PIT II’s mysteriously resurrected detective any day of the week. Give me open endings and ambiguities and all the potential they hold. So much better than being force-fed tidily under-done conclusions. Of course, then there are revelatory conclusions done so well that they’re mind-blowing, and those are great, and another beast entirely…I’m put in mind of books like The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch by Philip K. Dick, to cite an obvious and classic example. At a certain point, all the threads of the story come together and the epiphany arrives so subtly and seamlessly that it’s startling. I wanted to immediately go back and reread the book to see how it had been done. Another book would be Hermann Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game, which has to be one of the most patiently-wrought examples of world-building in literature. And the great thing is that, because the majority of the action takes place within an insular academic world, so much of what we glean of the outside world and historical events is from the things we aren’t told, and the mystery of all that we don’t know—all the tantalizing missing pieces—helps create this enticing, shadowy outline of things.

DR: Yes, it seems very clear that you do not distinguish much between different types or genres of writing – between ‘literature’, ‘pulp’, horror, fantasy, crime, or whatever terms people want to use.

AZ: No, I don’t make a distinction between them. I’m going to go wherever the journey takes me, wherever I want and need to go, and borrow from any genre and discipline and style to create work that’s meaningful to me, and hopefully to readers, as well. That’s part of the fun, the excitement, and the work will be better for it. Literature should have no boundaries. Every genre has something of value to offer to the reader and, when in the hands of a skilled writer, that genre can prove moving and inspiring, and can add something to the greater culture. It’s a landscape truly without limit. As a reader, I’ll never live to experience it all and that fills me with sadness.

DR: Maybe there are certain different foci and types of energy, but not much more beyond that? And with far more overlapping than setting them apart.

AZ: Yes, exactly. There is a lot of overlap in my work as well, I think—SF and fantasy and horror and magical realism, and often with an introspective, so-called “literary” emphasis. Some call that type of writing ‘slipstream’, but to me it’s more simply cross-genre. You’d mentioned some of the experimental influences you see in my writing. I think my early stuff might have some leanings in that direction, though I couldn’t really point to any particular writers or books that served as any sort of model. For me, it’s often the idea rather than the final executed book that inspires me most when it comes to experimental forms. For example, I love the idea of Kathy Acker, and I admire what she’s done on the whole for literature, and I’ve enjoyed several of her books, but I’m not sure those books have inspired me to head down a similar path or anything. I like having a narrative thread to follow, which in some experimental works is either absent or so subtle that it’s impossible to detect, making for obtuse, impenetrable texts that read as though they were probably fun and exciting for the author to write, though much less engaging for the reader (this reader, at least!) to sift through for meaning. On the other hand, I do love writing that takes chances. Crucially though, it’s not only writers commonly classified as being from an experimental school who do that. We’ve already talked about Delaney, Ellison, Hoban, and there are plenty of others both in and outside of the speculative fiction field.

DR: In spite of the wide range of influences, it’s clear that there are plenty of recurring themes and motifs in your writing. Innocence against the darkness of the world is one that I see a lot. And a sense of release from that world, in various ways. One that stands out, perhaps related to both of those, is the prevalence of cults. Why is this particular theme important to you?

AZ: I find fringe religion fascinating. Partly, because I feel I understand its allure on some level. And also, I’m drawn to the tragedy of it, the tragic circumstances of the people drawn into groups like this, because the inevitable question arises, of what compelled them to leave behind their former lives, shed their individuality, and join collectives that promise them…what? Salvation of one form or another, I suppose. I think a lot of people are running from some type of psychological trauma and pain, and hope that the group will care for them, almost like surrogate families. Some might argue that there are only superficial differences between cults and greater organized religions, that the latter cause just as much damage to certain individuals or groups. History certainly bears out this viewpoint.

DR: And potentially other types of organization that promote a strong sense of ring-fenced identity.

AZ: Yes. This is a much greater conversation and probably beyond the scope of this interview. But yeah, I can empathize with the cult disciple, I think. There were times in my life when I felt lost, adrift, and yearned for someone to offer me assurances that everything was going to be alright in the end, to take me into some greater protective sanctuary.

DR: Oh yes, very much the same here. Maybe this is a universal feeling.

AZ: I suspect so. Luckily for me, I suppose, I’ve always had a streak of mistrust toward people. It’s a good thing that I counted books among my friends and family. It’s hard to find better teachers than books. Who knows where I’d have wound up otherwise? This goes back to my childhood years. Here in Windsor, Ontario, Canada, we’re a border city with our American neighbour, Detroit, Michigan, across the river from us. Growing up, my family would watch as much news that was local to Detroit as to our own city, and at that time in the 1980s Detroit was known for its shockingly high crime rates. Watching the news was terrifying for me as a little kid, constantly being inundated with these horrible true stories of murder, rape, armed assault, etc., and it really instilled a kind of fear and wariness in me. I became distrustful of others, and to a large degree that never went away. But that’s okay with me, as I believe that caution is always best, generally speaking, and I’d rather be informed and aware than oblivious and a potential target for something unpleasant. And that fear of the horrors rampant in our world has certainly found its way into a lot of my writing.

DR: One thing that becomes apparent when reading your writing is that, when you choose, you pull no punches whatsoever. Your work is not afraid to explore some of the darkest aspects of humanity and human emotions. That inevitably brings us to the whole concept of the transgressive, which can be a surprisingly complicated area since it covers everything from writers deliberately setting out to shock as far as possible through to an inevitable part of existing as a human being that is merely presented without curtains, as it were. Something already familiar from a million news stories. I am curious about your relationship with all sides of the transgressive. Do you ever actually set out to shock deliberately?

AZ: More often than not, any transgressive elements come out naturally, I think, though if it has ever been deliberate, it would only be because I thought the subject worth writing about, and to bludgeon the reader over the head with in the most visceral way possible so that the message comes across as clearly as I can achieve. Sometimes I’m surprised by things that have been classified as transgressive in my work, or in the work of other writers, usually because it addresses some prevalent thing I see going on in the world today.

DR: Something that needs to be talked about or examined but that is actually more likely to be side-lined?

AZ: Yes, I suppose. To me that seems less transgressive than simply topical. Or if it’s something that isn’t specific to a particular moment in time, then something pervasive that we all see all the time. In these cases, I get a sense that it’s more a matter of what some of us pretend we don’t see, or actively avoid confronting. I do understand the desire to protect oneself from such things and wish the badness away, and I feel it’s healthy to do so from time to time, but to ignore those harsher aspects of reality seems unwise to me. And so we see a lot of strong reactions to transgressive elements in writing, sometimes outright hostile, as if the writers who work with that type of material are seen as engaging in something seedy or reprehensible, or that it makes them unhinged individuals. Far from it. It probably, I sense, makes them well-balanced in that they’re accepting of the eclectic nature of the human experience.

And then there’s the other side to that, the books we’re told are dark and frightening, but are really just hackneyed plots with the same bogeymen told in the same-old familiar ways. It does make sense, as it’s the safer territory—we’ve all seen it before, and so while we acknowledge that it’s intended to be frightening, there’s also the unspoken certainty that we understand it, and that this understanding diminishes any potential threat to our frail courage and sensibilities. We can get through that horror, but if we read something that borrows from the daily headlines, sometimes that proves to be a little too much, a little too close to home for comfort? I suppose it’s a need for escapism, even within genres that pride themselves on confronting our darkest fears. Show me an urban legend-type shaggy monster crashing through the underbrush: great! Show me the serial murderer next door…Let’s get back to that cousin of Sasquatch in the woods, shall we? Ha ha.

DR: Or the horrors caused by society itself and what it considers acceptable and unacceptable?

AZ: Yes, indeed. By the way, I’m not being disparaging of these works that deal with, say, cryptozoology and all the classic horror and fantasy tropes you can name. When done well, in the hands of a good writer, it can be wonderful and very original. I only mean to suggest that there’s a peculiar dichotomy between the things that are often considered acceptable and unacceptable within genres that, by definition, deal with concepts that are dark, strange, and disturbing on either an intellectual or more visceral level. In fact, going further than that, fiction generally should express all aspects of the human experience, so I’ve never understood the shock and revulsion some people feel when encountering certain subjects in books. If you’re alive in the world today, and at all attuned to what goes on in it, then nothing in a book should be exactly surprising. If one reads something that disturbs and decides to stop reading that book, that’s well and fine. But when that person decides it’s time to burn the book and get the pitchforks out and go after its author, that’s not.

DR: How do you find yourself handling such censorship or self-censorship? It seems to me that there is a continual tension going on here, maybe even increasing now thanks to advertiser-focused online platforms and the powers of social networks. Does this bother you and affect how/what you write at all? What would you say authors should do in the face of this?

AZ: Well, one need look no further than the everyday world to see examples of horror and atrocity happening in our daily lives right alongside the good and positive things. And so for transgressive literature to address that darker part of the duality seems not only reasonable to me, but important, and a positive thing. It goes back to the relevance of transgressive writing in bringing things into the light that otherwise might remain hidden from a lot of people. It’s a kind of sharing of knowledge, and a reminder of the world we live in that could at any moment unleash the best and the worst we have to offer each other. So that’s a positive thing, I think, to have the availability of works that courageously address things of this nature. One of the wonderful things about fiction is that it has a real power, a power to effect change, to make people see something through a different perspective than their own, and thus to potentially foster sympathetic viewpoints or compassion for another person.

We live in a world of extremes, and I feel the overwhelming need to reflect that in my writing. Which is why my collections have such a wide range of emotions. I often follow darker, heavier stories with gentler ones, both for the sake of variety and also to give the reader a breath of fresh air before dropping something ugly in front of them again. Every day we hear news of something great being done, somewhere, by good people for the benefit of others. And, every single day, we hear news of atrocities happening. Atrocities globally, and sometimes local to where we live. The goodness is an inspiration, but so is the badness—the former gives me hope, the latter makes me angry. Writing when I’m feeling hopeful has led to some of my favourite stories of mine, and the most reprinted. Writing when I’m angry has led to a substantial body of work, too. J.G. Ballard was, I believe, talking about his novel Crash when he said that he “wanted to rub the human race in its own vomit, and force it to look in the mirror”. When you feel helpless, powerless, frustrated by all the injustices you encounter, I can understand that desire to hold a mirror up so we can all see exactly who and what we are…and how we might do better. That’s the full equation, and a pretty fine mission for any writer.

DR: And yet I never get the feeling that your writing is so message-driven that it stops being primarily about the story. One of the strongest aspects is the balance you strike between the basic human urge to express that outrage and horror at the world, and also the basic human urge of storytelling.

AZ: Yes, the story is always the most important thing for me. It can certainly be the vehicle for underlying messages and themes, but without a narrative those elements would just be the equivalent of me ranting. There’s enough of that type of thing with social media, and I don’t feel like contributing to it…I much prefer sticking to writing fiction rather than Facebook tirades.

DR: Talking of messages, how much do you find your own personal experience bleeding over into your writing? Or do you tend to write in a more abstract and removed way?

AZ: It’s a lot of both. There have certainly been times when personal experiences have served as the catalyst for a story. For example, my wife and I used to live in the downtown core of the city. There’s a lot of crime in that area, but it really hit close to home when we learned of a violent hate crime that happened right outside our home. It was one of several reasons we were so eager to move, which we did shortly after. Not that I’m naïve enough to believe that a relocation within a relatively small geographic area will magically eradicate all incidences of bigotry and violence like this; but still, the move across the city has been to a much quieter, much more peaceful neighbourhood—and symbolically it felt important, to remove ourselves from what had begun to feel like a nexus of bad happenings and people advocating horrible views. One other positive thing that came out of that experience was a story I wrote inspired by it—inevitably, it was a nasty story, because it was inspired by such a horrific event with some truly awful people. And I think depicting people—even the bad ones, maybe especially the bad ones—truthfully is important because it’s an accurate reflection of the world. It might make for a difficult read, but I think difficult reads can be important. I have books on my shelves that fall squarely into this category, and they had a profound impact on me, validating my own fears, proving that facing certain things head on was meaningful to their authors, to their publishers, to their readers. And they’re books I treasure, though some I rarely go back to because, as I said, they’re difficult territory to navigate without getting an unsettling and powerful emotional blow. Like a lot of great books, the mere idea of them, and the reminder of them through their physical presence on my bookshelves, is an inspiration, both to be bold and truthful in my own writing, to never shy away from telling things the way they are, and also a reminder that art that remains truthful is important, just as these books are important to me.

When writing from experience gets a bit too heavy on the soul or just plain boring, it feels wonderful to detach myself from personal inspirations and delve into much more abstract terrain. It helps to have a wide variety of interests and therefore influences to draw from, I guess. Some personal experiences are one-off and solitary, others come from deeper places and are more renewable. Plenty of good but some not so good, as with anyone. The traumatic experiences I won’t go into, but they’ve certainly informed a certain amount of my output over the years.

DR: The reverse question could also be interesting. Do you find what you write bleeding over into your life at all in terms of how you function as a person?

AZ: Yes, I’ve experienced that. I think a focus on certain elements in my writing makes me hyper-aware of their prevalence in the everyday world. I’m talking about some of the darker subject matter that, just as my being conscious of its existence outside of my writing will inform my writing about it, it likewise runs the other way, as well. It’s a permeable membrane, for sure. That said, even the gentler, more melancholic stories will sometimes fill me with nostalgia for whatever may have inspired them, and so I’ll find myself pining for something now lost to me—a certain time of my life; certain people who I was close with but have parted ways with; certain places that I haven’t visited in years calling to me with voices so strong I’ll actually feel compelled to go and revisit them. This sort of completes a cycle and starts it going all over again, because at that point I feel so overwhelmed with emotional connection that I want to document it and, more often than not, it finds expression in some new piece of witing.

DR: Thinking back to your first published books, I believe Black Sunshine and Experiments at 3 Billion A.M. (which I published myself back in the day), how do you find that you have changed over time? Has your style or approach changed much in the intervening years?

AZ: I don’t think my approach has changed all that much, in that it’s always taken one of two modes: usually, letting the story come to me, waiting for the idea to arrive and then running with it. And, less often, making an active decision to tackle a particular subject. The latter scenario usually comes about when it’s something that I haven’t written about before thematically. Its newness might set it apart in my mind, make it something I’m thinking about a little more objectively.

One thing that’s changed is the ease with which I’m willing to call a story or manuscript finished. I learned the hard way after looking back at my early books and being unhappy with certain aspects of them, mostly the mechanics of things. This is a positive thing, in that I feel I’ve grown enough as a writer that I can now pretty readily spot where I might have done better work and where I’d improve now. In the case of Experiments, my first collection, you were obliging enough to release a second edition a few years back that allowed me to correct some of its initial shortcomings. Though, as you know, I still feel that more needs to be done to get it to where I’ll be happy with it. A third edition sometime down the road, perhaps? I promise I’ll have gotten the experiment right by then, ha ha.

So really what’s really changed is my perspective on the whole idea of “completeness” when it comes to my work. Before, I would finish a number of drafts and believe the story in question was finished. Now I have a much more malleable notion of the process—I don’t think any story, at least my own, can ever truly be called “finished”. I have no problem editing my work for reprints and future editions, in minor enough ways that the overall integrity of the stories isn’t changed. I want the reader to get the best version of that story that I’m able to offer at any given time.

DR: I know that feeling – whether anything is ever truly finished.

Yes, we never quite get there, do we!

One other thing that’s changed is a focus on what I think of as “renewable characters”. Maybe this is an influence from pulp literature, which as I’ve said I love. I’d done this sort of thing when I was young and writing my first stories, though it kind of went away as time went on, and by the time I’d started getting my work published it had all-but disappeared. And then, probably around the time when I was writing a lot of the stories that became Blacker Against the Deep Dark, I noticed it happening again. That is, I was writing self-contained stories featuring recurring characters, characters that had something colourful or otherwise memorable about them that made them stand out from the other stories.

In BATDD, it was the Clark and Kessel characters, the detective partners in the near-future SF-horror novella “Journey to the End of a Burning Girl”. Since then I’ve written a novel-length manuscript of self-contained stories with these characters, one story of which is going to be in my forthcoming collection from your Eibonvale Press. In fact, that collection has a few stories featuring such renewable characters, who feature in their respective ongoing series of self-contained stories that form greater manuscripts. I really enjoy writing this type of character and find it renews my enthusiasm for writing in general when conditions might otherwise make the task difficult. So I think my new book will stand apart from my previous collections for this reason, for its unique and renewable characters whose respective stories will feel both complete and yet open-ended, as if there is more to come…and there is.

DR: Your previous book, These Long Teeth of the Night, was a compendium of your best stories from 1999 to 2019, published by Fourth Horseman Press. Now, you’ve got a forthcoming book through Eibonvale Press, which we’ll be working on later this year. That seems a good opportunity to talk about the future – this book and other things. Can you give us a run-down of what we can expect to see?

AZ: That book, Beware Us Flowers of the Annihilator, is a collection of dark cross-genre short stories. Science fiction and fantasy and horror, and with a couple of darkly humorous stories, which is something somewhat new for me. This one took a very long time to finish—I’d thought it was completed nearly two years ago and then scrapped a bunch of the stories when I realized they weren’t as strong as the others. I wrote some new stories for it and I’m just giving a final-final polish to the whole thing now. I’m proud of it. It’s the best of my collections, I think. It was difficult following up These Long Teeth of the Night, because those stories had been around for a long time, and so more than ever I felt the need to make sure this new collection was the strongest I could possibly make it. I can’t wait for the cover to be unveiled—it’s a thing of beauty, a painting by the talented Carl Lavoie, who’s had work published in Vastarien and elsewhere. I’ll say no more about the artwork, but let it speak for itself. It’ll speak volumes all on its own.

In the meantime, I’ve got new fiction coming out in Amazing Stories Magazine, and reprints in translation in several magazines, including stories in two issues of the Romanian SF magazine Helion, as well as a pair of stories and an interview in the Ukrainian horror magazine, Babai. It’s so nice to see such thriving genre communities everywhere.

DR: And any other news beyond the books themselves?

AZ: In the last quarter of the year, I’ve got a story in an anthology being launched as part of an event I’m helping to curate called Weird Windsor. It’s a celebration of speculative fiction writers in our city and surrounding areas, as well as visual artists and musicians who identify their work as being in some way spec fic-inspired, or just plain “weird”. The anthology will collect new and reprinted work from writers, as well as artwork. The event will have readings, musical performances, and writers and artists selling their work. We’ve never had an event dedicated to speculative fiction here, and considering the rich and diverse community of spec fic writers we have, it’s high time we did. And so finally we are.

Onwards!

DR: Yes – onwards! It feels a long climb up a steep path sometimes, but that’s the nature of what we do, of course. To end with, let’s enter the land of make-believe for a moment. Imagining that there were somehow no impediments, either financial or bureaucratic, what would your ideal existence be? Where and how would you live and pursue your writing in this land of dreams?

AZ: Well, the first thing I envision in this make-believe scenario is an absence of the chronic pain I suffer from, and which makes concentrating on my work tougher than it used to be. I receive regular treatment at a pain clinic and do physiotherapy at home and though it helps, some days are still significantly more frustrating than others.

Beyond that, you and I have long fantasized about the founding of a colony, a retreat, a refuge for writers and related art-minded misfits. I say let’s do it. Here in Ontario because I’m familiar with certain parts of the province and can vouch for the beautiful landscape. Also, our healthcare system is a pretty good one. So yeah, let’s fortify ourselves in a secluded rural area, on a lake, in some small town up north of where I live here in Windsor. Does this sound suspiciously like the founding of the cult scenarios we were discussing earlier? Well, this is different. Here, nobody would get hurt. Here, there would be an end to pain. There would be only art, and peace.

…It does sound like a cult, doesn’t it?