By Eugen Bacon

Undugu—it’s a Swahili term for kindredship. It’s not far off from “ujamaa,” a premise of sharing and togetherness that was President Julius Kambarage Nyerere’s socialist experiment when the United Republic of Tanzania first gained colonial independence. Ideally, ujamaa should have worked—it’s a beautiful and generous concept. In practice, it wasn’t quite the success it was meant to be. So there are also inherent risks with “undugu”—because kindredship means inviting others into your personal space. It’s a trust relationship founded on goodwill. And this is what it means to collaborate: to trust, to respect, to have goodwill in the understanding that all participants are beneficiaries of the outputs, that we all put in effort for the best outcome(s).

Undugu—this is what I aim to achieve in my collaborations. And they’re many.

The most powerful and, hopefully, the longest lasting of them is the Sauútiverse. Back in November 2021, Wole Talabi, one of the founding members of the Sauútiverse, reached out to African writers for expressions of interest in becoming part of a collective, to create a shared world using the Syllble platform. A bout of brainstorming sessions followed, in which we determined our vision as holding the key tenets of collaboration, support, creativity and Afrocentric-based storytelling. The Sauúti Collective, as we named the founding members, comprised ten African writers and creators from Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania and the diaspora—Haiti. Together, we created a new world, the Sauútiverse: an Africa-inspired secondary world with humanoid and non-humanoid creatures in a five-planet, binary star system with a shared history, and the presence of sound magic.

The name Sauúti is inspired by the Swahili word “sauti” which means voice or sound.

The five main planets, each named after the words for ‘song’ in various African languages, are:

- Zezépfeni—from the Amharic word “zefeni”

- Wiimb-ó—from the Swahili word “wimbo”

- Órino-Rin—from the Yoruba word “orin”

- Ekwukwe—from the Igbo word “ukwe” meaning “song” or “anthem”

- Mahwé (before its destruction)— from the Kirundi word “mawe” meaning “mother”

- There is also an inhabited moon, Pinaa, from the Setswana word “pina,” meaning “song.”

These genre-bending worlds are the perfect setting for black speculative fiction stories. Members have shared in various interviews and articles what being part of the Collective behind the Sauútiverse means to them, including in a conversation published in Brittle Paper and titled “The Sauúti Fictional World: A Partnership Between Syllble and Brittle Paper.” In a question on what it personally means to create in the same world with other African writers, they answered:

I have always believed that “The only way forward is to work together.” Like I heard my old man once say to a friend of his that “Eni to fe Yara, nise lo da rin, Eni to fe lo jina, nse lo mu awon ara e dani.” This translates into: “if you want to go fast, go alone, if you want to go far, go together.” The cast of Writers and Creators in this project so far are so immensely talented that I feel honored every time I am in the same space with them. I believe that consensus of this nature is the true way to make progress and make giant strides for African Speculative Fiction

Kalejaye Akintoba

~

At first I was unsure of the process, never having done it before, and not knowing how I could add value or input. But the first session really opened me up to the other contributors, their skills and knowledge, that is already making the world-building fun, interactive, and most of all extremely prolific in covering so many aspects that a single writer or creator would battle to do themselves. We quickly saw where each person’s interests lie, and that means areas I may find out of my depth will be picked up by another contributor or contributors. Or I might find a partner-in-crime to go into things I’m keen to investigate —and then be able to throw ideas around. It’s been fascinating to see how it has evolved and where we all agree on the direction of certain aspects.

Stephen Embleton

~

There is a sense of many hands working with something malleable, like mud, and the joy that comes from watching such a vast world take shape. This constant spinning exchange of ideas and the multiple points of view cohering into one wide whole. Most exciting is the many writers who will come to this world and create stunning work that we who worked on its origins couldn’t have seen coming. Making this open imaginative system with so many different Africans who are professionals in their varying fields, but also intuitive and attentive to detail is a continuing honor.

Dare Segun Falowo

~

It’s an honor and a joy to collaborate on building an Afrocentric fictional world. There’s something really powerful about bringing minds together and watching the most extraordinary, exciting ideas take shape on this scale and to have the opportunity to learn about different African cultures. Most importantly, I love knowing that what we build in this project will belong to any and all African writers that want to play in this world.

Cheryl Ntumy

~

It feels really good, to be honest. I feel seen. Since 2018 when my novella The Book of Lost Words got some recognition at a manuscript contest, I do not think I have really had this kind of exposure to other writers and creatives. You know writing is primarily a solo endeavour. But this is very exciting, and I look forward to making the most of it.

Ikechukwu Nwaogu

~

I believe almost every writer begins by writing fan-fiction. Our earliest stories are usually inspired by other stories we’ve heard or read or seen and want to see continued in some way. I also stumbled into my writing career by working on stories with other writers and I learned a lot from those interactions. I think having a shared world takes us back to the core of our creativity and learning and opens us up to even grander stories. To do this with a cohort of very talented Africans of varied backgrounds is a pleasure and one I think we will all benefit from.

Wole Talabi

~

On what motives creativity, Adelehin Ijasan wrote:

Writing is a form of expression for me. On the occasion I come up with something I think is really cool, I want to share it with others. Being mind blown by some piece of art, short story, movie or comic, also sets me on fire and I’m desperate to evoke a similar feeling in others.

Adelehin Ijasan

~

Also on creativity, fellow Collective member Jude Umeh wrote:

An inborn need to play and explore, coupled with the right role models who make it ok to indulge and find satisfaction in creative pursuits across a spectrum of art forms. Creativity inspires creativity, and each story told or art completed only sparks more of the same and/or better interpretation or extension of itself.

Jude Umeh

On specific areas of individual story focus in the shared fictional world, Xan van Rooyen wrote:

Definitely the music and magic and the culture this system would create, bringing in the religion as well. As a musician who was always taught to read music, the concept of oral traditions, of knowledge being passed down and shared without the need or desire to write it down has always fascinated me and this is a concept I am keen to explore, especially in the context of how vulnerable that knowledge and cultural heritage might be to loss and corruption. Having read and loved works by Akwaeke Emezi, I am also keen to explore gender and gender identity in a more specifically African context within the world we create.

Xan van Rooyen

In his introduction to the inaugural Mothersound: The Sauútiverse Anthology, founding member Guerrier had this to say:

I have a dream of a future when creative writers around the world will wake up and their natural inclination will be to collaboratively write and produce within the unique story worlds they create.

In this future, writers from different backgrounds, locations and cultures will imagine deeply together, they will be more empowered, they will work hand in hand, side by side in artist collectives. In this future, they will fuel our ability to collectively imagine with more complexity, more profoundness and more beauty. This future, I believe, is already here, and it is called ‘Sauúti’.

Guerrier

I connect with all these motivations behind the Sauútiverse. Writing black speculative fiction is important to me, as I wrote in the Brittle Paper interview:

Speculative fiction is a safe way to explore our world meaningfully, creatively. In its generality, encompassing fantasy, science fiction, horror and the paranormal, it explores the diversity of our world and the universe beyond our understanding. It’s about interrogating possibilities in the exact meaning of the world: to imagine, to conjecture, to think, to reflect, to fabricate… Speculative fiction can be a powerful tool of subversive activism for an author as an agent of change to explore themes relating to climate change, social injustice, greed, politics, racial inequality and more, in worlds parallel to ours.

Eugen Bacon

I am a mother, a woman, a writer, an editor, a scholar, a colleague, a mentor, a friend. I am passionate about: motherhood, climate action, social justice, stories of culture, tradition, our past, our future, black people stories… The creative space where I tell stories is literary speculative fiction. I write and perform short stories, novels, novellas, prose poetry, and creative nonfiction. Being an African outside of Africa, especially as a creative, I discover myself every day in fiction, as a way of navigating my otherly space of hybridity, betwixt, a sum of parts—I am many. The more I write myself in, the more I see myself. The more I ‘become.’ The more I embrace my past, my present, my future.

The Sauútiverse is especially fulfilling to me, and I have written a novel, a novella, and many stories in this world. Our first anthology, Mothersound, is holding its own in awards and recognitions. Stephen Embleton’s novella “Undulation” won the Nommo Awards for speculative fiction by Africans, and Cheryl Ntumy’s short story “The Way of Baa’gh” was a finalist in the same awards. The anthology was a finalist in the British Fantasy Awards, achieved a starred review from Publishers Weekly, made the Locus Reading List, and was shortlisted for the British Science Fiction Association (BSFA) Award, with some individual short stories and artwork from the anthology also longlisted.

“Mothersound is a primal scream that shatters all that has been done in the past. Sauúti is a unique mythology that is challenging dominant Western narratives, ways of thinking, and stories that have been so much rooted in the legacies of Western colonialism and individualism,” says Guerrier in the foreword.

Wole Talabi agrees. “We believe the Sauútiverse can be the next step in the evolution of African speculative fiction by being a sandbox for generations of African and African diaspora writers to work together and imagine endless possibilities,” he says, also in the introduction to Mothersound.

Indeed. We are guts into our next anthology, Sauúti Terrors, and thinking ahead to more anthologies! I am co-editing Sauúti Terrors with members of the Collective Cheryl Ntumy and Stephen Embleton, as I continue to navigate my other spaces—with like-minded creatives. What’s particularly refreshing about the Sauútiverse is its openness to other members who were not part of the founding team as our expansion continues. In Mothersound, we published non-founding members, and there will be more in the new anthology, Sauúti Terrors, which will also include Afrocentric poetry. As you can see, undugu is inherent in the Sauútiverse, and we continue to hum the song of Our Mother, the Creator from the creation myth by Wole Talabi and Stephen Embleton:

Khwa’ra. It is acquired.

Ya’yn. It is uttered.

Ra’kwa. It is released.

An Inner Gaze into the Sauútiverse

And now, I will tease excerpts of various stories from members of the Collective, as published in Mothersound:

“What Has No Mouth? (A Fragment From Our Sonic History, On Alleged Utterance of The Mothersound Among The Surali of Wiimb-ó” by Dare Segun Falowo:

Wet salt burned Ikululu’s eyelids. He would say he was unsure of the source of his tears, and maybe blame them on the acrid smoke or the ash blowing about, but the gnaw of Erigiga’s absence was scraping against his ribs. It felt like a black hole had opened inside his stomach. He tried to remain mute, because a maadiregi only makes use of their voice when it is most important but the sound of his brothers and sisters openly wailing around Erigiga’s pyre made him let go, to ragged sobs.

Introducing this story, Talabi writes:

In this Wiimb-ó-set story, we learn a fragment of sonic history, from 300000 juzu [year] B1B. It is a tale of the Surali, who are a group occupying an isolated continent of the planet, much like our own Australia, that must rediscover and reclaim their world using the primordial power of sound that drives all things this universe, its magic, technology and people. And we follow the Surali as they also learn of what can happen if that power, the Mothersound that animates the Sauútiverse, is not handled with care.

~

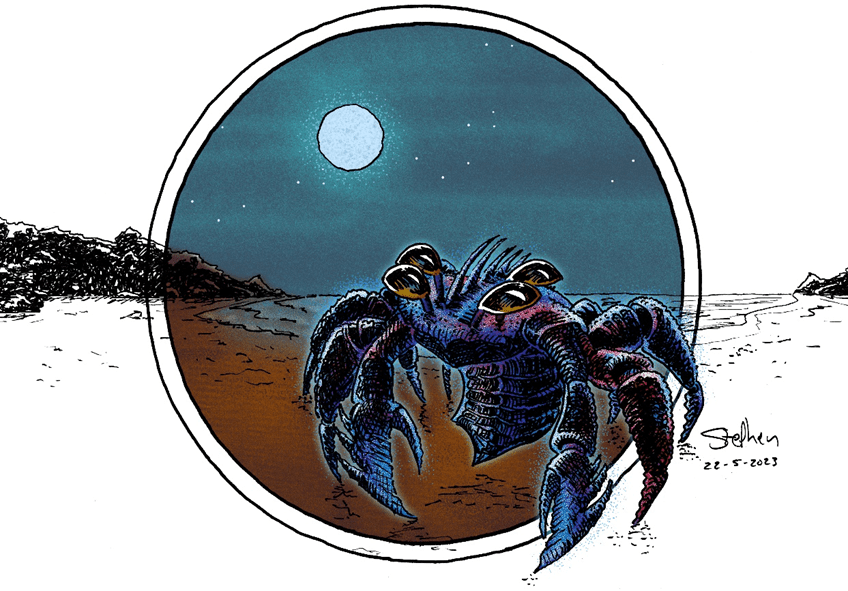

“The Way of Baa’gh” by Cheryl S. Ntumy:

Easing sideways into a cove, I sink below the sea, pincers opening wide as the cold water soothes my pain. I can’t go back to the safety of Kuu’uum. Not when I’m the only Og’beh left in the colony who hunts true Nududu.

A ripple moves through the water as a zje’lili fish passes me. Designated Nududu thirty generations ago for their ability to glow in the dark, the soft billowing creatures have shown no growth since. I turn my gaze to the plants that rise up from the water, seeking more promising prey. Their bright leaves and long stalks mock me. Same as last juzu. Same as ten juzu past. Everything the same, generation after generation.

Only Baa’gh change.

Introducing this story, Talabi writes:

One of the important non-human intelligent species of the Sauútiverse are the Baa’gh, who played a pivotal role in another major event of the physical history of the Sauútiverse – the destruction of Mahwé… In the following story by founding collective member Cheryl S. Ntumy, which takes place in 2000 juzu before the first Boāmmariri (five year event, meeting of the interplanetary council), we learn how Ss’ku, one of the Baa’gh—a crab-like species on Mahwé who have a unique way of evolving by consuming other creatures, and who have been oppressed and mistreated by the empire-driven humanoids—played a role in the failure of this grand experiment on Mahwé. It’s a wonderful story about generational strife, evolution, power and folly of empire that sets up much of what happens down the line in the Sauútiverse, beautifully told from a very non-humanoid point of view and culture.

~

“Xhova” by Adelehin Ijasan:

I named you Nitiri. All the other automatons addressed their children by their batch codes. You were not X Æ A-116 to me. You were Nitiri from the old Mahwé myth. Nitiri, who faced the frosted ice giant on the melting ice caps of the North Pole and defeated him. Nitiri who was beauty, fertility, grace, and goddess of nature. A mortal who attained godhood by sheer will. I called you Nitiri, and when words finally coalesced on your tongue, you called me Apa! Father. I was Father. You would stare at me when you suckled at my breasts, little hand reaching up to touch the cold lenses that were my lidless eyes. You would stop intermittently to smile and chuckle. It was in my code to simulate love, but I was never created to feel it the way I did. To love you as humanoid fathers loved their daughters—without calculation, purpose or condition.

Introducing this story, Talabi writes:

And so we come to this epistolary tale by Sauúti collective founding member Adelehin Ijasan, told from the point of view of a semi-independent parenting automaton under the control of the master AI on Pinaa. It takes place several generations after the destruction of Mahwé and the events of the previous story, about 900 juzu B1B, when the AI is at its most overprotective and Pinaa, as a consequence, is at its most isolated.

But every creation carries the seeds of its creators and the AI was made by the people of Mahwé. Which means that yes, it carries within it their desire for control as well as their capacity for fear. But that also means it carries their capacity for love. For revolution. And perhaps… for something more.

~

“Sina’ by Eugen Bacon:

The girl, Rehema’re—it means blessing—her echo does not come with light. She speaks good Sauúti. She bends her magic, can do many things with it. Hers is a good echo. It has transition, reflection. It’s long and deep with superior timing. Wey ma. Wey ma. Uuuuuuu.

Sina is not laughing now. The impudu-pudu’s echo is a bellow, infiltrating with such loudness, it hurts his ears. And the smell! It started off from a distance as a sickly-sweet odour of turning fruit, mingled with a stench so foul it pulled water from his eyes. Closer, the lightning bird has the stench of putrid onions. The odour of a rotten klalabash. The stink of bad t’apiapia fish. The pong of fresh faeces from an old stomach. The spray of a dying chekele’le beast—the laughing one, greedy as sin and with its shorter hind feet—moments before its bowels collapse.

Introducing this story, Talabi writes:

This story takes place centuries after the independence wars, 15 juzu A1B, when a loose federation of planets has been formed with representatives from each planet present to discuss trade, maintain peace, etc. Told from multiple viewpoints during a hunt, it is the lyrical and lovely story of a child on Ekwukwe who does not fit in, who is born missing something the culture deems fundamental, and yet, finds a way to become more than what he seemed destined to be at birth. To become more than anyone could have expected. To become a legend.

~

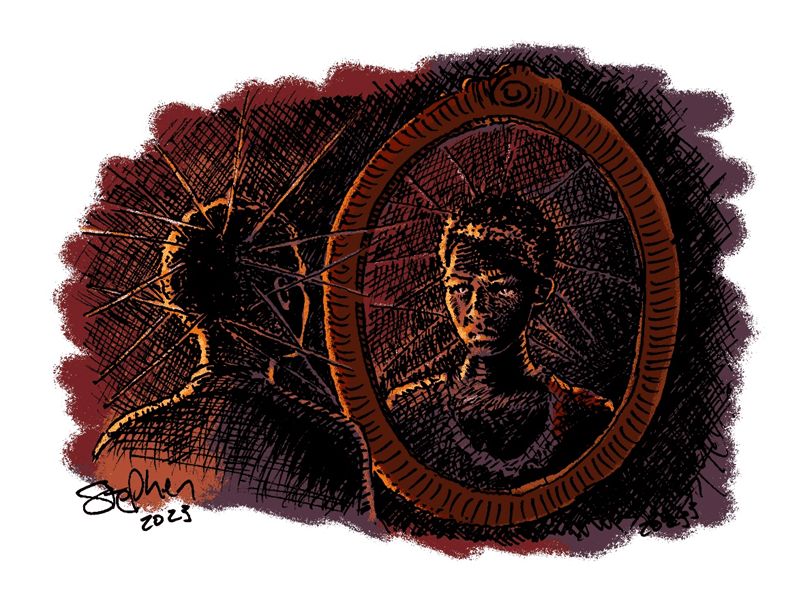

“Undulation” by Stephen Embleton:

She let out a whoosh of air until her lungs were empty, while both hands pushed outward, completing the signing of the words as she understood them:

It is acquired. It is uttered. It is released.

The recognisable tingle formed on the tip of her tongue, warming her face, as she slowly took in air. A low vibration rippled through her. The magic was in her.

For Hmahein, that was the easy part. The beginning of the Creation Myth always stuck in her throat. As a ruevaagi, a bearer of histories for the worlds, a word should not be a hindrance.

She shook it off and locked eyes with her reflection in the wooden-framed, oval mirror of the small shrine.

She blocked out the word pulsing in her mind like a racing heartbeat. She blocked out the dimly lit room, draped in fabrics, curtains and intricate rugs. She blocked out the wafting scents of the dried kalabash vine leaves burning in the brass bowl on the small table, below the mirror.

She watched her mouth open, hands poised at the ready, and closed her eyes.

“Our Mother,” she began.

Introducing this story, Talabi writes:

In this story by Sauútiverse founding member Stephen Embleton, which takes place 90 juzu A1B, we dig deep into the creation myths and epic poems and also the people who tell them. The ruevaagi, custodians of knowledge. Like African griots of old, they are tasked with telling the people the stories of themselves. But they are still under the sway of Zezépfeni, and can only tell the official version of events. They travel the five worlds, spreading the stories of what happened, performing it. Soft power. Even though there is nothing soft about it.

~

“Muting Echoes, Breaking Tradition” by Eye Kaye Nwaogu:

Na-Achana was finishing the last of her meal when she heard the call. As always, she had the eating area to herself, having come late to avoid her fellow students—something she always did anywhere outside of class. It was easier that way. It was not that she hated people; she was just tired of the constant looks of pity they always gave her. It was not her fault that she was an orphan, her family having been killed when she was a child, and she was being raised and sponsored by The Order of The Silent Sisters. She longed to feel a sense of belonging, to be part of something bigger, something more, but the Silent Sisters were not exactly the best definition of a family. The most they were good for was the vast library, with its millions of sonic recordings and stories. Like stories of the Akalala and the change its call heralded. But Na-Achana didn’t believe in myths and fairytales. Her life had been too harsh for those.

She finished her food, cleaned up and hurried briskly to her tent.

Introducing this story, Talabi writes:

So now we come to this story by collective founding member Eye Kay Nwaogu which takes place 35 juzu A1B. It examines the echo of violence from the past in service of empire and its impact on the future, as represented by children, like our protagonists. For this story, we first go back to Wiimb-ó, to a school where two students from different worlds find themselves linked by history. Echoes of actions taken long ago. Echoes of truth and violence. They must choose what to do with the knowledge, and chart a course for the future, for better or worse.

~

“Kalabashing” by J. Umeh:

Muji-Aah brushes back his thick dreadlocks as he looks up at the ceiling, the distinctive silvery sheen of his skin catching the harsh electric light and giving his skin a semi-luminescent, metallic appearance that sharply contrasts the strange, dark, tattoo-like markings around his entire body. He whistles out a deep breath.

Mother God, help us.

Never in all the nineteen juzu he has lived has he experienced this level of excitement and trepidation, not even before the previous bés’s semi-final performance, or his first sono-aural sexual experience on Ekwukwe. No. There has been nothing like this, the feel of having something you’ve always dreamed of being at your fingertips, just one performance away.

Muji-Aah has never fit in. Always felt like an outsider. His unusual skin and natural affinity for technology marked him as an outcast even when he was a child. But he knows he can’t be alone. He wants to explore the system, find people like him or at least find his place in the Sauúti system. He seeks people who understand what it means to be an outcast. Which is what bonded him to the twins, the other members of the band.

Introducing this story, Talabi writes:

In order to choose a group that will give the opening and closing performance at the event—a series of local talent contests are held. This is where we find ourselves at the start of this story by J. Umeh, a founding member of the Sauúti collective. We go back across the binary star system, to Ekwukwe, where we meet a very special band of musicians vying for the honour of playing at the 40th Boāmmariri, 200 juzu A1B. A story about the joy of performing and sharing music with others. Even when that music literally has the magic stripped out of it. Of course, the members of the band bring their baggage and their drama and their talents and their gifts with them. And lurking in the background are the hands of Zezépfeni, always seeking more knowledge, more control.

When all of these things are shaken together and allowed to run over, well, we get something special. We get… Kalabashing.

~

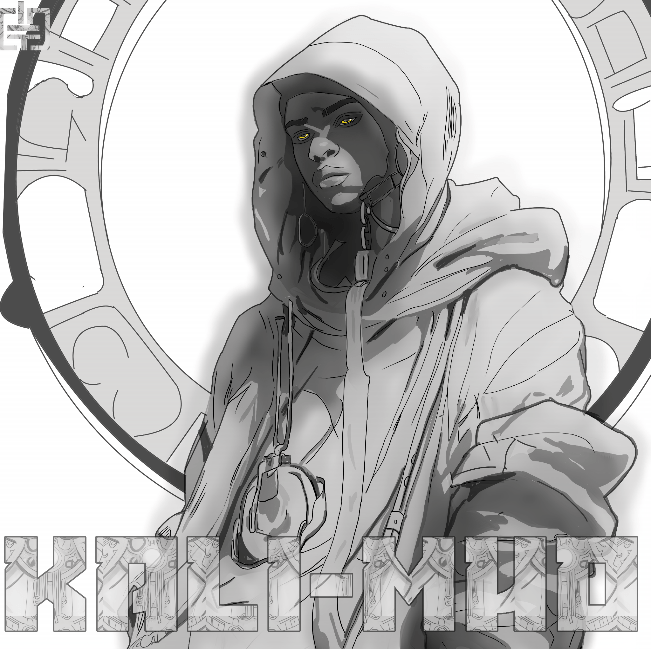

“Lost in the Echoes” by Xan van Rooyen:

Ruk shuddered and curled his fingers, magic sizzling through his sinews. He was trying to do the right thing even if it might be too late to earn his people’s forgiveness, to repair the trust he’d shattered when he’d broken the rules governing his power.

The club would be closing soon as one sun set and the other rose somewhere far above the mire of the city’s lower levels.

The patrons would have to emerge groggy and disorientated, disgorged from reverie but hopefully rejuvenated. Ruk surrendered to sensation as he embroidered the air with a final rising melody over the pounding bass.

The dancers contorted, limbs plucked by melismatic tendrils of power, faces seized in ecstasy. When it was over, the club-goers staggered, released by magic but still drunk on music: their auras more consonant, their souls soothed.

Introducing this story, Talabi writes:

Enter Ruk, or Ruk’ugrukun kel Az’zagru, our deaf protagonist of this wonderful story by collective founding member Xan van Rooyen.

A citizen of Órino-Rin in 400 A1B, about 200 juzu after the events of the previous story, Ruk has a unique ability similar to that of the Kali twins combined, but perhaps more potent.

Ruk is unable to hear sounds and lacks a perceptible sound aura or ‘echo’ of the Mothersound but can feel the sounds made by others, interpret the fundamental vibrations of the world, of people. And Ruk can even manipulate them, though this ability comes at a price, the price of pain. He is a runaway from his nomad tribe, working in the clubs of Órino-Rin as a kind of DJ, performing un-restricted, illicit music-magic until, as we find out in this story, he gets caught in the web of a Korp power play and is forced to make a difficult choice.

~

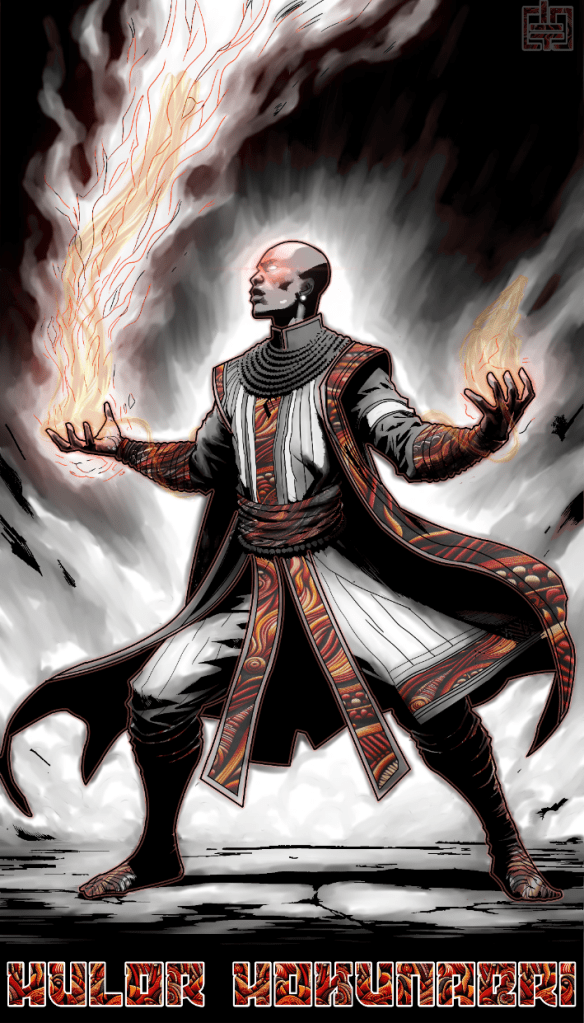

“Hologhiri” by Akintoba Kalejaye:

1. The Failing Wall

The sky raged pink and green on Zezépfeni.

In the hall of a large stone temple, its walls pulsing with energy, twelve figures wearing dark red robes sat in a silent conclave. Wires and circuits jutted out if their bodies like vines.

Their robes pulsed with the same energy that ran through the walls. They spoke to one another, not with their voices but through thought. The subject of their discussion could not be uttered, secrecy could not be broken.

Their facial expressions changed rapidly, the only evidence of their communication. From shock to anger. From indignation to frustration. And then, collectively, resignation.

Finally, one of the figures waved a hand, and suddenly, they were in the middle of a dark sphere, the spectrum of color leeched away. Not even faintest trace of color remained within the space. There was only light and dark. The space hummed.

The motion of the figure’s hand coincided with movement of lips. “They are breaking through,” the figure said. “The Hogiri Hileh Halah is failing.”

Introducing this story, Talabi writes:

Being the closest to the outer boundary of the system, Zezépfeni are the first to discover a secret about the nature of the Sauútiverse. That Nga’phandileh, powerful beings of unreality that exist in a parallel dark dimension, want to enter their space and claim it. And just like the people of Zezépfeni, the Nga’phandileh too are motivated by more than mindless desperation for power. Even the monsters seek a kind of justice as you will come to see.

So, the leaders of Zezépfeni take it upon themselves to keep this a ongoing war a secret and maintain the reality border, constantly seeking new knowledge, new powers to help them hold the Nga’phandileh at bay.

Now, in this fast-paced, epic story also set in 400 juzu A1B by founding collective member Akintoba Kalejaye, which sets up a lot of what is to come from this world, we dig into the details of this border. We meet the people that control it, the warriors that protect it and of course, the creatures of unreality themselves that threaten it.

This is Hologhiri.

Outside Mothersound, here is an excerpt of Wole Talabi’s story “How To Win The G’idiidigbo Challenge: A Practical Guide” published in 99 Fleeting Fantasies, an anthology by Pulse Publishing:

1. Don’t panic.

Remain calm when you are chosen to represent your family on the silent grounds. You must fight Kele’leke of Yu’usara to settle the dispute that has festered for more than twenty juzu, despite the best efforts of the elder’s council. Thus, it comes to this. The ancient way. Each family has chosen a member of the opposing family to do battle. The Yu’usara have chosen you because they think you’re the weakest of your clan. They have chosen you because you’re small, with a moderate echo and a tilt in your gait courtesy of scoliosis.

Your spine may be bent but your will isn’t.

2. Train twice a day.

At dawn, practice movement. At noon, spar with your sister Ireno’ore in the garden. Do so in silence. All children on Ekwukwe are taught the fundamentals of combat. But the only way to win the G’idiidigbo challenge is to be prepared. The only way to be prepared for a fight is to get into one. Ireno’ore is skilled, and she has a good echo. You hear it in her motion, the potential for magic if she spoke the right words. But the challenge demands silence. There will be no magic.

When she catches your kick and lands a clean cross to the left of your jaw, fall and look up at the sky where the suns Zuúv’ah and Juah-āju are staring down at you, their heat tickling your sweat-slick skin. Pray to the Mother for strength, then get up. Continue.

3. Rest.

There should be no sparring the day before G’idiidigbo. Spend the daytime alone by the river. Swim across it a dozen times.

Spend the night in your grandfather’s glass and metal compound where there is a tiny opening in the ground that’s linked to the network of underground caverns beneath the planet. Listen to your younger brother sing the Rakwa wa-Ya’yn. Go to your grandfather, hug him when he begins to cry. Nod confidently at Ireno’ore. Give your mother a reassuring look, repaying her for the unwavering support that persists even now.

Luxuriate in the love of your family. Listen to their echoes.

Structured as a numbered list of steps to win a challenge called G’idiidigbo on the planet Ekwukwe, this story follows a young woman who has been chosen by her family to represent them as she prepares for, and participates in, this cultural rite modelled on sports and other forms of cultural competition that include controlled violence. Many of such rituals were, and are, still present around the world, including in Africa. The story emphasizes the importance of preparation, skill, cheering, and community support in such encounters.

You can see the recurring themes of sound magic, tradition, mythology, community, a longing to belong, and more, in these stories. The Sauútiverse is a home for undugu, kindredship, and ujamaa—sharing and togetherness. It’s a beautiful and generous concept, and we hope this trust relationship founded on goodwill will continue to be a success, as we trust and respect each other, beneficiaries of our outputs for the best outcomes.

References

Guerrier, Fabrice (2022), ‘The Sauúti Fictional World: A Partnership Between Syllble and Brittle Paper’, accessed 29 March 2024. brittlepaper.com/2022/06/the-sauuti-sc-fi-fantasy-world-a-partnership-between-syllble-and-brittle-paper/

Guerrier, Fabrice (2023), “Foreword”, in Talabi W (ed) Mothersound: The Sauútiverse Anthology, Android Press: Eugene, Oregon

Publishers Weekly (2023), Mothersound: The Sauútiverse Anthology, accessed 29 March 2024. http://www.publishersweekly.com/9781958121603

Sauutiverse (2024), Sauuti.com, accessed 29 March 2024. sauuti.com/

Syllble (2024), Sauúti, accessed 29 March 2024. syllble.com/sauuti/

Talabi, Wole (2023), “Why We Created the First Collaborative African Sci-Fi/Fantasy Universe”, in Talabi W (ed) Mothersound: The Sauútiverse Anthology, Android Press: Eugene, Oregon

Talabi, Wole (2022), “How To Win The G’idiidigbo Challenge: A Practical Guide”, in Brozek J (ed) 99 Fleeting Fantasies, Pulse Publishing: Spokane, Washington

Bio:

Eugen Bacon is an African Australian author of several novels and collections. She’s a British Fantasy Award winner, a Foreword Indies Award winner, a twice World Fantasy Award finalist, and a finalist in other awards. Eugen was announced in the honor list of the Otherwise Fellowships for ‘doing exciting work in gender and speculative fiction’. Danged Black Thing made the Otherwise Award Honor List as a ‘sharp collection of Afro-Surrealist work’, and was a 2024 Philip K Dick Award nominee. Eugen’s creative work has appeared worldwide, including in Apex Magazine, Award Winning Australian Writing, Fantasy, Fantasy & Science Fiction, and Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction. Visit her at eugenbacon.com.