By Cyril Simsa

My late father, the Czech composer and broadcaster, Karel Janovický – born Bohuš František Šimsa in Pilsen in 1930, but better known under the pseudonym he adopted in the 1950s to protect his parents, whom he had left behind in Communist Czechoslovakia, when he skipped the border during the Cold War – died in January 2024. He left behind a four-storey Victorian terrace in North London, crammed with music, books, and papers, including 250 or so classical compositions and a not inconsiderable personal archive.

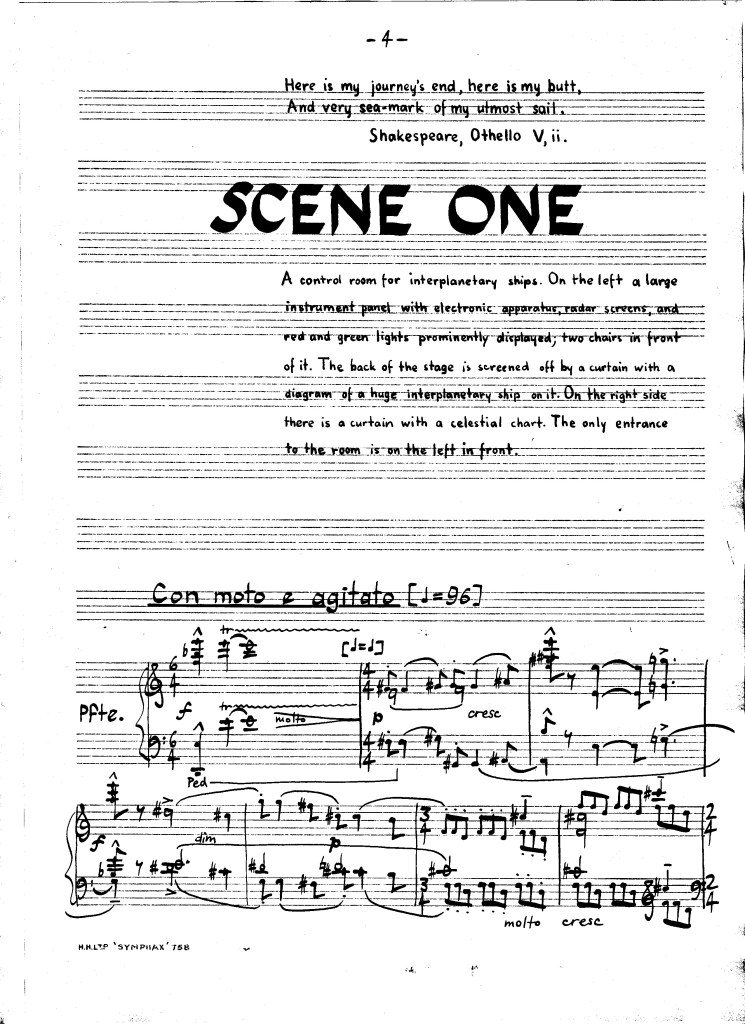

It was in his papers that I found a booklet with the libretto of his one-act opera, The Utmost Sail, which he wrote in 1958 to an English-language text by another Czech émigré, Karel Brušák (1913-2004). The booklet is mimeographed, fanzine-style, so it is not a professional publication; but to anyone familiar with the history of fanzines or sf fandom, the format will be immediately recognisable, and I assume this is something that he or Brušák must have had printed for the benefit of future producers and performers at around the same time they were finishing the work itself.

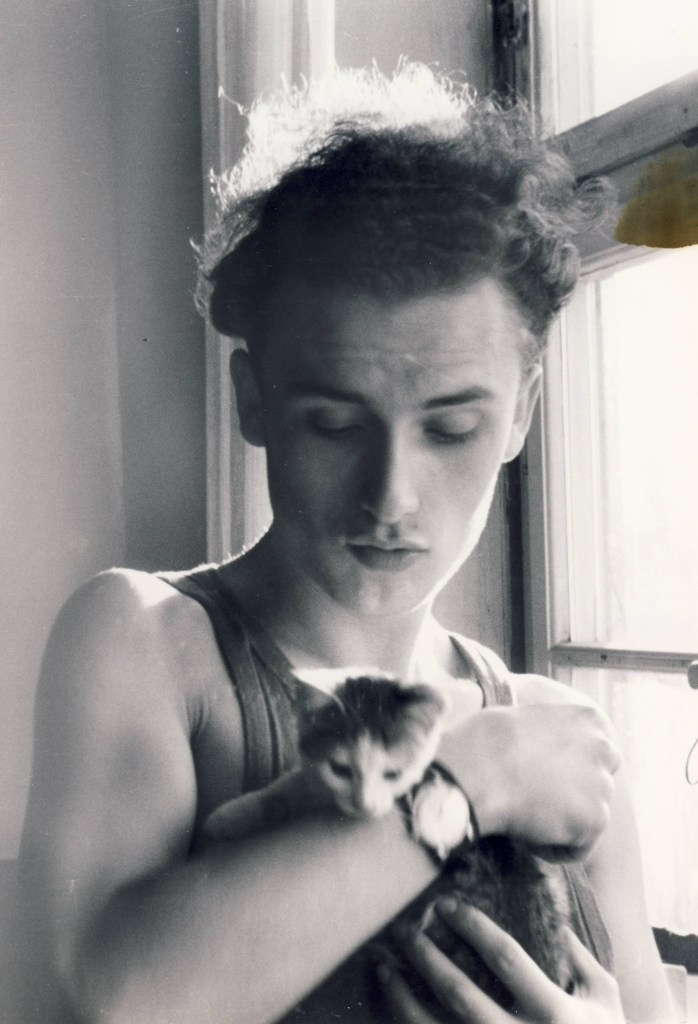

Karel Janovický, Ludwigsburg refugee camp, Germany, ca. 1950

I had been long aware that my father had written an opera, and back in my teenage years, when I was at the height of my initial involvement with science fiction, he had even told me it was set on a spaceship. However, in the way children have of ignoring their parents, I had never actually seen a copy or read the text. And while I have still not seen a performance, the libretto can stand on its own as an interesting example of mid-20th Century European sf theatre.

So how did this peculiar artefact come to be? From my father’s side, the motivation was primarily musical. After emigrating from Czechoslovakia by illegally crossing the line of the future border fence on foot at night (a family history fictionalised in my story, “Queen of Šumava”), and a sojourn in various refugee camps in Bavaria, he came to Britain on a music scholarship in 1951. By the mid-1950s he was established as a freelance pianist, music teacher, and composer with occasional gigs at the BBC World Service as part of his performance circuit.

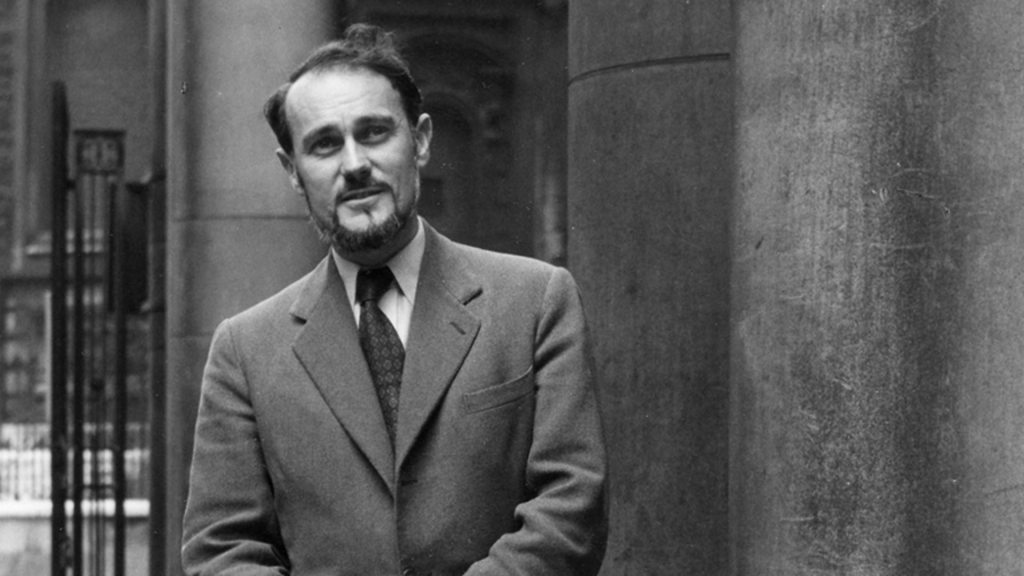

Karel Brušák (1913-2004) was an émigré of an earlier generation. Having completed a Master’s degree at Charles University in Prague in 1937, with a thesis under the supervision of Jan Mukařovský of the famous Prague Linguistic Circle, he was in Paris, continuing his studies, when war broke out. Following an adventurous escape from occupied France via Gibraltar, he ended up in Britain, where he worked in civil defence (specifically as one of those ARP wardens so lovingly mocked by classic TV sitcoms), alongside more substantial engagements with the Czechoslovak Government-in-exile and the BBC. After the War, he became a key employee of the BBC World Service, and that was where the two men met (Slobodová 2009, 219-221; Pynsent 2004).

Karel Brušák, London, 1956

My father, in a memoir written after Brušák’s death, describes it thus:

The Czechoslovak Section of the BBC World Service – devoted routinely and almost exclusively to current affairs – used to let its hair down at Christmas by putting on a Nativity play written and produced more often than not by Karel Brušák. The beginnings of my own broadcasting career date from one such occasion. It was, I think, a week or two before Christmas 1955. I had been brought in to play the piano, but an unforeseen shortage of shepherds discovered during rehearsal led to me being asked additionally to voice one. Further jobs followed (Janovický 2004).

The specific impulse that led to them attempting an opera was a competition that had been announced by the Italian music publisher, Ricordi:

When the Italian publisher Ricordi posted up a competition for a one-act opera to be delivered in 1958, I had no difficulty in persuading [Brušák] to write a libretto for me. He chose a science fiction subject: an idealistic scientist sends a four-man spaceship he calls Messenger into the cosmos; soldiers try too late to have the mission aborted; the crew watch helplessly from space as Earth is consumed in a nuclear holocaust…

There are two scenes, one on Earth, the other on board the spaceship; the stage set is identical: a control room (Janovický 2004).

Given the limitations imposed by the one-act structure and the single set, the writers were not able to incorporate a lot of action; instead, they used their two groups of players (on deck and at mission control) to relate the wider story of the controversial launch and its repercussions second-hand. This tendency to describe what is going on in the outside world, rather than making any attempt to show it, is reinforced by the fact that Brušák’s interest is evidently philosophical, not technological. He wants to consider the implications of humanity breaking free of Earth, the planet on which it has its roots, rather than the mechanics of any such action. In both scenes, Brušák thus interpolates the kind of discursive interventions on science and philosophy that are characteristic of so much Central European sf writing of the mid-20th Century – the “philo-dump”, if you like – rather than following on-stage character interactions of heroics. (Think Lem, or Nesvadba, or further East, the Brothers Strugatsky.) Indeed, Brušák’s characters are never named, just given symbolic roles – “Captain”, “Scientist”, etc. – so their identities are defined entirely by their functions, not their personal characteristics.

The Utmost Sail: first page of mimeographed libretto

The two scenes of the bare-bones plot are then used to present two different examples of social breakdown. On Earth, the chief scientist strives to defend the noble aims of his visionary, well-intentioned project, even as a party of rogue military officers take over the control room and declare that the peaceful rocket programme is dead, while the monitors in the background start to show traces of other, more lethal launches. Meanwhile, in space, the astronauts try to fill the endless hours by debating the point and purpose of their mission, but their underlying unease and rising personal tensions eventually lead to violence. In both locations, the inability of (at least some of) Brušák’s protagonists to maintain their sense of a separate identity in the face of epoch-making events ends in destruction and death. This is humanity’s Achilles heel, suggests Brušák. “[Brušák’s] choice of the subject was weirdly prophetic, for as we were feverishly working on the opera, the first Sputnik flew on 4th October 1957,” commented my father (Janovický 2004).

In its overall tone and structure, the libretto of The Utmost Sail is nothing like the genre sf with which modern audiences are familiar. One can see that Brušák’s sources were not the genre writers of the 1940s and ’50s, who had been trying to imagine what real-world space flight might actually be like, based on contemporary science, but the more speculative genre-adjacent writers of an earlier generation. (The title of the opera is taken from the last act of Shakespeare’s Othello, ca. 1603: “Here is my journey’s end, here is my butt,/And very sea-mark of my utmost sail”; and the text also incorporates a quotation from William Wordsworth’s “Peter Bell”, 1819, which shows how far outside the genre Brušák went for his points of reference.) Space flight, for Brušák, is not a technological proposition, but a thought experiment, and his rockets and control panels are set dressing. He is thinking about the psychological impact of radical scientific change on human society and psychology, what would today be called a “paradigm shift,” not the nuts and bolts; he is clearly more than a little sceptical about the ability of individuals to absorb change that happens too quickly. To paraphrase: if you move fast, you break things.

Possibly because of its theatrical structure, the most obvious antecedents that springs to mind for the way the libretto is written are the sf plays of Karel Čapek (1890-1938), in particular R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), (written 1920, first performed 1921), which dramatises the effects of another world-changing technological innovation on humanity. The parallels are evident in the way Brušák’s text uses its sf elements as a hook on which to hang more general philosophical considerations; in its basic insight that the collision of runaway technology with the self-interest of human elites can be disastrous; but also in the way the restrictions of the physical set led both writers to tell so much of their story off stage, narrating outside events by passing them through the closed circle of the somewhat clinical command and control centres they both chose as their focus, rather than the wide-screen dramatics that would have been possible in cinema. Interestingly, Čapek himself wrote an early essay on the differences between theatre and film for the dramatic artist, which pointed out this precise difference in the opportunities offered by the visual image and the spoken word (Čapek 1927, 111-113).

The Utmost Sail: first page of vocal score

Brušák was not a big fan of Čapek’s work. In fact, it is a matter of record that he considered Čapek a “bad writer” (Slobodová 2009, 225, translation mine) and from my own limited social contacts with him in the 1980s, this is also something I heard him say myself. Nonetheless, when it came to writing an sf play, his solutions to depicting a sweeping sf scenario in the limited space of the theatre are quite similar to Čapek’s. It is impossible now to be sure how deliberate this was, but Brušák was enormously well read and was also of the generation that would have had the opportunity to see at least some of Čapek’s plays in their original Prague productions. (Not R.U.R., which would have had its premiere when Brušák was seven, but quite possibly the later sf plays, like The White Plague [1937], and any number of revivals.) One assumes Brušák must have been aware of this similarity and perhaps enjoyed a sense of amusement that his text had ended up paralleling the work of a writer, of whom he disapproved, though it is notable he did not follow Čapek in tacking on the crowd-pleasing, saccharine happy end that so undermines R.U.R.

Unfortunately, Brušák and my father did not succeed in the Ricordi competition, and the opera was never published: “We didn’t get the first prize, but it was quite an exciting project” (Vaughan 2007). However, a Czech translation of the libretto did eventually appear in a posthumous collection of Brušák’s poetry and prose (Brušák 2009) and a limited number of the fanzine-style edition of the English text is still in circulation. Unlike my father’s chamber music, which is performed periodically in both the Czech Republic and the United Kingdom, the opera remains unproduced, presumably because of the expense and the investment of time that would be required… Which surely must present an opportunity to some enterprising opera company.

In later life, my father became a full-time BBC World Service producer, rising eventually to be the head of their Czechoslovak Section, while continuing to write music. Brušák was hired by the University of Cambridge to teach Czech and Slovak in 1962, and remained in that role till 1999, thereby becoming one of the founders of contemporary Czech and Slovak studies in the UK. His pupils included Prof. Robert Pynsent, later at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies in London, and Prof. James Naughton of Oxford (Pynsent 2004). He collaborated with my father on one further song cycle in 1981.

A scan of the full score of the opera is available on request.

Sources

Brušák, Karel. 2009. “Nejzazší plavba”. Translated by Zdeněk Hron. In Karel Brušák: Básnické a prozaické dílo, edited by Vlasta Skalická. Cherm.

Čapek, Karel. 1927. “Hranice filmu.” Lidové noviny, November 18. Reprinted in Karel Čapek, O umění a kultuře III. Spisy XIX. [On Art and Culture III. Collected Works XIX.] Československý spisovatel, 1986, and cited from the reprint. The title of the essay translates as “The Limits of Film”.

Janovický, Karel. 2004. “Karel Brušák, the BBC and Music”. Manuscript sent to the author by e-mail, July 11. Draft contribution to an unidentified newsletter; I have not been able to establish where this was published.

[Pynsent, Robert]. 2004. “Karel Brusak: BBC’s voice of hope for Czechs and Slovaks during the Nazi tyranny” [obituary]. The Times, June 17. https://www.thetimes.com/uk/science/article/karel-brusak-5ggdx9k6pxf [accessed 1 May 2025]. Although unsigned, this is widely attributed to Pynsent: see, for example, Slobodová 2009, 228.

Slobodová, Zuzana. 2009. “Karel Brušák” [afterword]. In Karel Brušák: Básnické a prozaické dílo, edited by Vlasta Skalická. Cherm.

Vaughan, David. 2007. “Karel Janovický – Czech sputniks in suburban London”. Radio Prague International, February 25. https://english.radio.cz/karel-janovicky-czech-sputniks-suburban-london-8610693 [accessed 1 May 2025].

Karel Janovický in his studio, London, ca. 2005

§

Fascinating, thanks. Perhaps it would have been worth mentioning more explicitly that Brušák had been publishing poems (and some lyrical prose) since the 1930s, so he was quite a natural choice for the libretto.

I bought his collected works years ago, but never got to reading it in full, and if I ever noticed the SF, I forgot about it completely.

An interesting comparison would be Harry Martinson’s Aniara (1956) – it is unlikely that Brušák would have known about it, perhaps except for brief secondhand descriptions, but again it seems to show something was in the air in the 1950s.