By Matt Finch

Introduction

What does travel through time and space reveal about the body?

This essay is an invitation to think about bodies moving through time in a work of contemporary literature. What is exposed about a body when it is displaced in time and space? The concept of the territorial body, developed from the pioneering work of Verónica Gago (2020), serves as a lens through which we can understand “the body of the individual person in the context of its entanglement with questions of territory, incorporating the complex multidirectional dynamics which arise between the individual body, the collective, and the various territories they inhabit” (Finch and Mahon, 2025, p.163). I also consider the temporal dimension of how “institutionally and culturally enforced rhythms, or timings, shape flesh into legible, acceptable embodiment” (Freeman, 2010, p.40). In this framing, the body is always the body in context and contexts, in turn, are changed by the bodies which populate them.

This lens is trained, here, on Kaliane Bradley’s 2024 novel The Ministry of Time. Bradley uses a science fiction conceit to bring together bodies from the territories of Britain’s past, present, and future. They populate a narrative which is at once a romance with sophisticated queer dynamics, a techno-thriller, an “odd couple” comedy of cultural misunderstanding, and a meditation on race and national identity in the era of climate crisis.

Kaliane Bradley, The Ministry of Time (Hodder and Stoughton, 2024)

The novel also provides the perfect opportunity for us to move Gago’s concept beyond the limits of “real world” plausibility; as one of Bradley’s characters puts it, “we are interested in the actual feasibility of taking a human body through time. Our concern is if the process of time-travel has major implications for the expat or the expat’s surroundings.” (p.37). From Bradley’s science-fictional vantage points, distinct interrogations of the territorial body can be made.

The territorial body in time

Gago’s original notion of the body-territory is “a practical concept that demonstrates how the exploitation of common, community (urban, suburban, campesino, and Indigenous) territories involves violating the body of each person and the collective body through dispossession” (Gago and Mason-Deese, 2019, p. 206). Expanded into the idea of “territorial bodies” (Sinclair and Spear, 2025), it is a frame through which to understand the individual body in dialogue with the territory in which it finds itself: who we are is always who we are in a given context.

Yet neither bodies nor the territories they inhabit are frozen, unchanging; as I have argued argued elsewhere, “The territorial body is to be understood not solely in terms of the conditions which have made its existence possible, but the ways in which it continues to become, and its capacity to move beyond its current form.” (Finch and Mahon, 2025, p.174).

Here we are in the realm of what Freeman (2010) calls “chronobiopolitics”, the study of how temporal schemae discipline and inform both individual bodies and entire populations:

In a chronobiological society, the state and other institutions, including representational apparatuses, link proper temporalized bodies to narratives of movement and change […] personal histories become legible only within a state-sponsored timeline (p.40-41).

Our births, deaths, marriages, and other life events acquire not just bureaucratic certification, but also their wider meaning within the polity. As Freeman notes, even in “zones not fully reducible to the state” such as psychiatry, medicine, and law, frameworks are in place through which lives become legible (p.41). This collision of place, power, time, and the individual resonates with the geographer Yi-Fu Tuan’s observation that “[h]ow time and place are related is an intricate problem that invites different approaches” (1977, p.179). We may spatialise time as a direction or destination, or consider spaces as processes with duration – from the growth, travel, and melting of a glacier to the ways in which a place like “New York City of the 1980s” is evanescent, time-locked, leaving us with only nostalgia, the desire “to revisit time like space, refusing to surrender to the irreversibility of time that plagues the human condition” (Boym, 2001, p. xv).

Fantastical genre works have allowed us to “visit time like space” in many ways, from the geographically contiguous timezones of Hoyle’s October the First Is Too Late (1966), Doctor Who‘s “The War Games” (1969), Sciamma’s Petite Maman (2021), the TV show Dark (2017), Leiber’s “Big Time” (1961), the temporal distortions of Priest’s Inverted World (1974), the Strugatskys’ Roadside Picnic (1977), or the parallel dimensions of Russ’ The Female Man (1975), where the same woman’s alternate selves prove to be entirely different territorial bodies in the Earth of each timeline.

In Bradley’s novel, we are invited to consider territorial bodies from across British history, plucked from their context, displaced to a near-future London, and subjected to the actions and scrutiny of the British state. Doing so creates a novel opportunity for a critique of Britishness, empire, and concepts of linear progress.

Bodies beyond

In The Ministry of Time, an unnamed British-Cambodian narrator moves from work as a translator with the Ministry of Defence to a new role as a “bridge,” supporting people brought from the past into the present via a new and secret device, the “time-door.”

These white Britons – knowingly labelled “expats” rather than “refugees” – are taken at what the historical record says was their moment of death or disappearance. The aim is to observe how they acclimatise to the present, and whether time-travel has any unexpected adverse effects on either the traveller or the world around them.

The project’s sinister leader, Adela, assigns the narrator to Royal Navy commander Graham Gore, a real-life Arctic explorer of the mid-nineteenth century whose entire expedition died after their ships were trapped by polar ice. As the novel’s intrigues proceed, contemporary events are interspersed with flashbacks to the expedition, Gore and the narrator fall in love, a conspiracy is revealed at the heart of the Ministry and actors from other timelines are drawn into a deadly conflict.

Through this plot, Bradley offers us a number of distinct territorial bodies drawn from across time and space, some by science fictional means, some by more conventional forms of displacement, but in every case revealing the “permeable boundary between the individual and the world they’d entered” (p.107).

First, there are the expats, often referred to by their year of abduction and therefore the historic territorial context from which they have been abstracted: Lieutenant Cardingham, taken from the 1645 Battle of Naseby; Margaret Kemble, from the Great Plague of 1665; Anne Spencer, extracted from the midst of the French Revolution in 1793; Arthur Reginald-Smyth, a Captain from 1916’s Battle of the Somme; and Gore himself, from 1847.

Displacement across time reconfigures each of the expats’ territorial bodies, creating fresh opportunities and threats as they find themselves anew in the context of a future era. They are laid low by the common cold, which has evolved since their time and proves a gruelling condition to shake – but the opportunities for personal change provide some consolation. Margaret, who had been left to die in a plague house, flourishes as a 21st century queer woman, enjoys dating apps, has a two-week stint as a Swiftie, and asks, “But would we not look well in thigh-boots and tabards broidered with FEMINIST KILLJOY?” (p.81).

Arthur adapts swiftly to swing dancing, performs mash-ups of Jackson 5 covers with a traditional hornpipe, and his search history encompasses “‘macarena,’ ‘brewdog,’ ‘clubbing,’ ‘ballroom,’ ‘vogue,’ ‘vogue dance,’ ‘madonna,’ ‘poppers,’ ‘rimming'” (p.161). Meanwhile Cardingham, veteran of the English Civil War, is “mainly interested in Minecraft and sex workers” (p.116) and resents his decline in relative privilege: “Where Margaret had gained ineffable ground, he had lost it. He burned with the anger of a child whose toys have been tidied away.” (p.141).

The expats discover era-spanning commonalities as well as differences, including a rueful observation by the narrator on their beverage preferences:

[…T]hey were more inclined to cooperate if they were given nice tea with a china cup and saucer – even Sixteen forty-five and Sixteen sixty-five, who didn’t have the manufactured appetite for it. Embarrassing stuff, something for a Punch cartoon about Englishness, but it worked. (p.54)

Some of the expats embrace change, while others seek to reassert the norms of the times from which they came. In doing so, the continuity of certain values becomes evident; the British state of the near-future finds as much use for Cardingham’s chauvinist violence as the seventeenth century did, recruiting him as an agent.

Gore, as the narrator’s principal love interest, inevitably becomes the focus of this exploration. In his own time, the naval commander “doesn’t like to think overmuch about his body, in case it remembers him and begins to make demands” (p.68), but the exigencies of Arctic territory have already intruded on him and his crew. Far from Blighty, the power and range of sailors embodying a global empire is reduced to the “wooden world” of their ships as microcosms. The expedition’s leader, representing the delegated power of the Crown, dies in a “desperately unhaunted room […] His avuncular ghost has failed to manifest.” (p.31). Men begin to waste away on short rations, and scurvy strikes, leaving their teeth “loose in the head as a blown rose’s petals” (p.67) and reopening once-healed wounds: in Gore’s case, a hand injury from a gun accident incurred elsewhere in the empire.

As conditions grow yet worse, the territory itself comes to define Gore. On solitary hunting expeditions, he

becomes, along the hallowing earth, a moving point of muscle and sinew, quite clean of thoughts. If he sees a quarry, he does not re-enter his body […] If there was someone with him, he’d have to remember he was fully inhabited by Graham Gore. (p.101).

Thanks to his extraction via the time-door, Gore ends up the “only one who still had a body to touch, to hurt, to yearn with” (p.262). By comparison, his future “plush-lined life” (p.58) offers little privation. He, too, becomes an agent of the Ministry; the narrator tells us “he was, above all things, a charming man. In every century, they make themselves at home.” (p.213) The disorientations of Gore’s temporally displaced body are rather different to those of the Arctic: he is troubled into compulsive handwashing by his introduction to germ theory, is bemused to be accosted as a “DILF”, and soon is “practically a native of the era:”

He wore button-ups and was clean-shaven to his cheekbones. He had a preferred washing machine cycle. Most mornings he rose – hours before me – and went for a run. (p.72)

An added wrinkle develops when it is discovered that the time-displaced expats must actively concentrate on their “hereness” to remain anchored in the present day. Spencer, an Englishwoman who has been taken from Revolutionary Paris, becomes “invisible in recorded time to all things but the naked eye” (p.118). Gore subsequently proves undetectable to airport body scanners; it is not mechanical recognition which is required to anchor the expats, but human acknowledgment within the territory they inhabit.

The need of the time travellers to maintain such connection dramatises the tension of accommodating oneself to, and sustaining oneself as, a displaced territorial body. The narrator muses that this might “bring a new facet to identity politics: ‘What time are you?’ ‘Are you multi-temporal or stuck in a time warp?'” (p.118).

As their stay lengthens, the expats are invited to travel throughout the British mainland, because the authorities

needed to see the expats move through broader geographical space without atomising into the scenery (or the scenery atomising around them) to know for sure that the twenty-first century had accepted their presence. (p.107).

The other antidote to the hazards of time travel proves to be music. A theremin obtained by Arthur – which not all of the expats can play with ease, because of their relative invisibility to machines – becomes one of the means by which the expats investigate their temporal “hereness” and “thereness” (p.169). (Gore uses it to play ‘Greensleeves,’ a tune which has endured long enough for them all to recognise).

The more sympathetic expats also come together in dance, both at Arthur’s Jackson 5 recital and at a dinner party where Margaret tells Gore, “You will instruct me in the polka, or I will step on your toes.” (p.124). Dance is, of course, an activity in which different bodies move together in time, here serving the process of synchronising bodies from different time-spaces, creating moments of togetherness and delight – even if a few toes get trodden on along the way.

Climate change and the territorial body

Even without the hazards of time travel, not all is materially well for bodies inhabiting the novel’s near-future London. Storms have grown so bad that local government delivers sandbags and prepares for flooding, while the media scrabble in the past for a stirring historic parallel to infuse Britons with resolve in the face of physical jeopardy: “Blitz spirit, the newspapers called this sort of thing, as if either climate catastrophe or the Blitz was a national holiday” (p.164). Gore’s newfound fondness for the bathtub, garnished with ice cubes, is also an escape from a “hellheight heatwave” (p.83), albeit an escape restricted by water rationing. Even as Margaret from 1665 marvels at the “miracle” of drinking taps, the narrator notes, “The UN reckon we’re three years away from the first large-scale water war.” (p.80). Significantly, the heatwaves “make time go utterly Dalí clocks”, leaving minds disoriented and bodies “poaching in [their] own sweat” (p.84). Under the light of a newly “acerbic” sun, the narrator “missed the shadows and the long English rains” (p.109). Every body becomes unmoored in time, and the homeland’s territory itself is rendered unfamiliar, as a result of environmental crisis.

Juxtaposed with the Arctic flashbacks, these visions reveal Bradley’s book as, among other things, a climate change novel. The Ministry of Time emphasizes that the territorial bodies which inhabit the nation-state will be transformed by climatic shifts. Bradley’s work can be taken as one possible response to Ghosh (2016)’s contention that the mainstream novel is incapable of coping with the radical and pervasive uncertainties of climate change, bound as it is by the imperatives of capitalism and empire. Bradley shows us that who we are arises from the dialogue our bodies have with the territory we inhabit – the physical climate but also the politics, economics, and culture of the day – and creates a novel of fractured, kaleidoscopic temporalities to undo conventional literary linearity. As the narrator herself notes in the novel’s opening:

Anyone who has ever watched a film with time-travel, or read a book with time-travel, or dissociated on a delayed public transport vehicle considering the concept of time-travel, will know that the moment you start to think about the physics of it, you are in a crock of shit. How does it work? How can it work? I exist at the beginning and end of this account simultaneously, which is a kind of time-travel, and I’m here to tell you: don’t worry about it. (p.5)

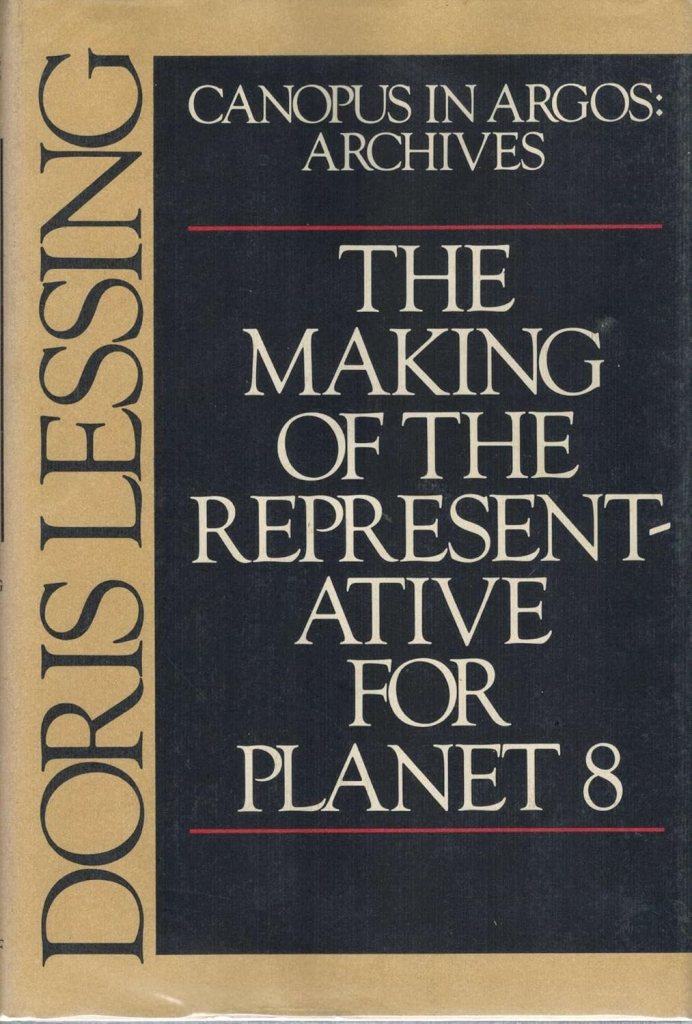

This is more than just conceit. It is necessary for storytelling under the radical uncertainty of a shifting climate. There is resonance here with Doris Lessing’s The Making of the Representative for Planet 8 (1982), which is also a novel about climate catastrophe and one which, through its afterword, reveals itself to also be in dialogue with Britain’s historic polar explorers, attracted at once by their heroism and repelled by their complicity with empire. (In Lessing, an entire planet’s culture and memory ends up decanted into a single survivor, the ultimate territorial body). Lessing and Bradley’s novels both, 42 years apart, can be seen as a dramatic puzzling-through of how we, as embodied beings in a given context, live with a colonial past, a fraught present, and the prospect of future instability.

Doris Lessing, The Making of the Representative for Planet 8 (Knopf, 1982)

Mutual recognition between the displaced

To protagonise this puzzling-through, Bradley grants The Ministry of Time’s narrator a biracial identity. She is a trusted servant of the Crown, a second-generation migrant from a non-Commonwealth country providing linguistic support to the Ministry of Defence.

Her family members have survived and thrived as immigrants precisely by making their new territorial bodies incontrovertibly manifest before the state, indulging a mania for documentation, garbing themselves in the paperwork of their new jurisdiction: “My family lived inside proof of ourselves like crabs in shells […] But no one was going to tell us what we weren’t entitled to or had failed to file.” She acknowledges that this “made me an excellent civil servant.” (p.71), and that she has taken every possible step “in my career […] towards becoming the monitor rather than the monitored.” (p.106).

These steps, however, only take one so far. Her ethnic inheritance goes overlooked by many, to whom “you look like one of the late-entering forms of white – Spanish maybe” (p.4), though when people learn of her heritage, they set their “eyes on that distant horizon where the genocide took place” (p.145) and make comments ranging from “Pol Pot Noodle jokes on first dates […to…] we loved Angkor Wat” (p.178).

This experience, alongside her work as a translator, allows the narrator to recognise the temporal expats as “internally displaced persons,“a bureaucratic term she had previously struggled to render into another language but which captures the interiority of migrant experience. She realises it applies to the time-travellers as well as her own mother, who had fled Cambodia, and perhaps even to herself: “a person whose interiority was at odds with their exteriority, who was internally (in themselves) displaced.” (p.26).

Yet the experience of being at odds with one’s exterior self also allows moments of unanticipated and oblique connection. Much to the narrator’s surprise, Gore defies expectation and sympathetically identifies her as “not […] wholly an Englishwoman”:

‘Well done,’ I said, as neutrally as I could. ‘What gave it away? The shape of my eyes?’

‘The colour of your mouth.’

The ice hit the bottom of my glass with a frigid knock. I’d never heard that one before. (p.51)

Gore’s unexpected ability to recognise and respect the narrator’s difference comes, in turn, from a tragic encounter during his imperial career, brought on by the hypnotic effect of the Arctic territory. During a hunting expedition, half-starved, out of water, Gore mistakes an Inuit man for animal prey, shoots and kills him. The dead man’s wife demands to see Gore, and it is this moment of contact, “a look that puts him against the horizon” and which “will linger on his body”, in which he notices that her “mouth is very beautiful, a colour that Gore will remember and try to name for a long time afterwards” (p.179-80), that underpins the intimate bridge Gore will be able to construct with the narrator beyond the horizon of 1847.

These characters are afforded new opportunities to see and be seen precisely through their displacement in time and space as territorial bodies: embodied beings awkwardly and incompletely disentangled from one context only to be enmeshed, equally messily, in another. Both Gore and the narrator accept this mess and find what is good in it.

The sincerity of Gore’s impulse to explore – including self-critical reflection on whether he truly behaved with compassion towards African slaves he rescued with the Preventative Squadron – makes him capable of transcending the time and space of his origin. This is mirrored by the narrator’s own flexibility and curiosity, recognising that the novel’s near-future setting “was the natural evolution of [Gore’s] England. I was the natural evolution. I was his lens if only he would raise me and look with me.” (p.107). The narrator sees the common ground easily, and frames it in terms of territorial bodies:

It was not unusual for me to look at my face and think What on earth is that? It bored me not to look the same as whoever I was with – isn’t that the whole point of being mixed-race? Oh England, England! The thing you do best is to tell a story about yourself. Graham Gore went to the Arctic believing that a noble death is possible because of all those stories and then he became a story. Oh England, you wanted to make stories out of me. (p.176)

As befits a narrator who is a former translator, connection comes through talk as much as touch, the ability to name and recognise a body, reminding us that “Language is a skin: I rub my language against the other.” (Barthes, 1978, p.73). She explicitly builds out the territory within which she wants to be understood: “Every time I told Graham something – about myself, about my family, about my experience of the world we shared – I was trying to occupy space in his head. I had ideas for the shape I should take in his imagination.” (p.176)

Throughout their journey to becoming lovers, their bodies affect one another no less powerfully than a jaunt through time – “the erotic charge of his bare forearms was giving me a headache” (p.108) the narrator tells us; Gore stutters over “your-your-funny little mouth” (p.174) which had initially given away her nonwhiteness to him; and the lovers even come to experience one another spatially (“He filled the room like a horizon”, p.108). This moves from idealization to a full recognition of the other’s embodiedness: “I was struck by the starkness of his crow’s feet. It unnerved me to see how human a body he inhabited.” (p.190).

Ultimately, the characters’ capacity to see and desire one another creates new possibilities for them as territorial bodies. In both, their sexuality incorporates elements of queerness. The narrator is fully beguiled by Margaret, finding even her pimples sexy and describing her physical beauty in woozy detail; at one point after merely regarding her, the narrator becomes “confused” (p.152) and rushes off. Meanwhile, Gore alludes to same-sex experiences on his naval expeditions, and cultivates a friendly intimacy with Arthur, who is clearly attracted to him, although it is left ambiguous whether Gore just has the nature of “an explorer whose life had required flexibility and forbearance” (p.141). More directly, Arthur says, “You can’t imagine what it was like to be a man of – of my persuasion, in my time. Now it seems I’ve got another go of it in an era that suits me better.” (p.209).

This is apt to the concerns of Bradley’s novel and the present paper: time-displaced territorial bodies are also desiring and desired, and as Muñoz (2009) argued, queerness is always imbricated with questions of other times, being, “a mode of desiring that allows us to see and feel beyond the quagmire of the present” (p.1) – precisely what happens to expats extracted from their own historic quagmires and flung into a new juxtaposition.

Collapsing fantasies of narrative control

Not only do the expats explore possibilities of desire and identity unavailable in their own time, but in Bradley’s novel, time travel itself is queered, in the sense put forward by Halberstam (2011): a failure to achieve instrumentalised goals, a deviation from the straight and narrow. The machine itself is a “door” which operates according to a bizarre logic, capable of only sustaining a certain number of time-displaced bodies at a given moment – and when an attempt is made to destroy it, it turns out that it cannot even be straightforwardly made to cease to function. It is a shift from the mechanical post-Wellsian model of time travel to something like the “arbitrariness of temporal pretexts” (Roberts, 2014, p.40) seen in older fantastic tales.

Further visions of the territorial body emerge when it is revealed that travellers from the future are also part of the plot. Impersonating present-day observers from the Ministry of Defence, the Brigadier and his compatriot Salese are agents from the 2200s, the era in which the time-door was created. In that time, a global conflict rages between a bloc incorporating the US, Brazil, and UK versus the “Tiger Territories”, an Asian alliance. The atmosphere is full of toxic waste from chemical weapons tests and London is no more. The time-door, an invention of their era, was built to fix the climate crisis through targeted assassinations of key figures, including those who “invested in weapons and manufacturing that were not what you probably still call ‘carbon neutral'” (p.300). However, these desperate, inventive, yet ill-resourced people are unable to rightly emulate the era to which they have travelled.

As a territorial body of the early 21st century, the Brigadier is a clumsy impersonation who refers to the BBC as “Auntie” and counter-terrorism police as “Special Branch”, and speaks with “an exquisite broadcaster plum I thought had died out in the seventies.” (p.58). His body marked by the privations of a desperate future, he turns “the white of used candlewax” (p.82) when he sees a generous tray of food. He and Salese have a “disturbingly makeshift” (p.118) vibe to them, but a keen understanding of how bodies experience pathology when displaced from their familiar context: “Oh, it’s not the century, it’s the soul […] Her ‘hereness’ and ‘thereness’ have no consistency, no continency, and she is beginning to slip out of time.” (p.117).

Ultimately, the project director Adela is revealed to also be a time-displaced figure, an alternate version of the narrator from the 2040s, her body made strange by the transfer to a new time and place. Her face is “pinched and hungry, and hauntingly as if her skin was held in place by a bulldog clip at the back of her skull” (p.75), the result of surgeries to address the side-effects of time travel.

Significantly, the main difference in Adela’s timeline and the narrator’s is the atrocity with which each of them motivates Gore to become a field agent of the Ministry. The narrator talks of Auschwitz, leading to Gore descending a bleak Google rabbithole. Adela had shared 9/11, stirring a fierce Islamophobic patriotism which makes Gore an unquestioning instrument of the future British state.

As the one who administers the time travel project on behalf of the state, Adela embodies what Roberts (2014) considers time travel as a fantasy of narrative control, noting that the time machine

makes dirigible something that had, hitherto, been imagined as beyond our capacity to control or steer. Dreams and magic happen to us, inflicting upon us a Scrooge-like passivity. Memory plagues us, or grants us wistful pleasure, but we can do nothing about the event that memory recalls. A time machine, on the other hand, is something we can control. (p.40).

“I had to make sure all this happened the right way” (p.301), Adela says of the events within which she is enmeshed, thinking not only of the state to which she has pledged her career, but her relationship with Gore, who commands the Ministry in her timeline and with whom she will have a son. She personifies Freeman’s contention that chronobiopolitics encompasses the individual lifetime as well as national history. As Adela fights to preserve the version of time she sees as “right”, events become increasingly bloody, ultimately costing the lives of several expats, the far-future agents, and others.

Rather than diverging timelines, the temporal intrigues of Bradley’s novel resemble a “thick present” (Sandford 2023), in which the dynamic here-and-now is always entangled with anticipation and remembrance. Seen in this light,

The future is always an aspect of the present. The future has not “taken place,” but the present always “holds” the future, and holds it as potential. Indeed, the future is never “later,” is it always (experienced, imagined) “now.” (Ramírez and Wilkinson, 2014, p.59).

Under such circumstances, time, far from being linear, is a messy, complex, endless immediacy. Time travel narratives thus become less about which “train track” of history we are riding, or the steering of destiny towards the “correct” trajectory, but rather about how we might shape the wet and ever-spinning clay of time itself.

As Adela says, history is merely “a narrative agreement about what has happened, and what is happening” (p.91) – here at the service of the interests of the British state. The past is tended to as “the familiar and collective legacy from which a group will draw a properly political future – be it national, ethnic, or something else.” (Freeman, 2010, p.41). Bradley’s narrator wryly confesses that this helps her to understand better “why the British history curriculum looks the way that it does.” (p.54).

Bradley’s novel shows us that the British establishment has, at best, been reskinned with a new, superficially more respectful attitude, including a “Wellness team” and offices in contemporary decor which consist of “interminable rooms: pebble-coloured with lights embedded in the ceiling, modular in a way that suggested opening a door would lead to another identical space, and then another, and then another” (p.7).

Such rooms imply an endlessness to contemporary British bureaucracy and its authority across time and space – although the chamber used to initially hand over the expats to the care of their bridges offers continuity to the past through its “air of antique ceremony: wood panels, oil paintings, high ceiling. It had rather more éclat than the modular rooms […] the room had probably remained unchanged since the nineteenth century.” (p.8)

This institutional design and control extends from decor to the realm of language. Post-imperial power saves its pomp for special occasions, but more fully permeates personal lives than ever before and even insists upon framing the narratives of those it has marginalized. At one point, the narrator and a Black British bridge, Simellia, are required to give pre-written presentations,

so didactic as to be oppressive. They made me read a lecture on multiculturalism, the bastards, leaving blanks for insert own experience here. I gave it in a monotone without lifting my eyes from the page then drank 250ml of white wine at a quaff; Simellia gently clinked her full glass against my empty, her jaw set (she’d been asked to deliver a lecture on post-war migration from former colonies and the Windrush generation). Control’s lectures were nakedly about getting the narrative right. (p.109).

This superficially less grandiose authority is no less rapacious, totalising, or cruel than any empire of the past. The bridges are repeatedly reminded that the ultimate purpose of the time travel project is above their pay grades; they are mere components of a wider apparatus, the Ministry itself, in service of a national hierarchy.

To what ends are this apparatus and its unusual capabilities directed? The answer appears to be extraction, exploitation, and harm. Britain’s time-door turns out to be plunder from the distant future, rather than the result of ingenuity. That future, Britain’s own, is murderous and vengeful. Our own protagonist is forced to confront a future self who is morally and physically deformed by her choices. Both versions recognise the need to turn away from the path Adela embodies; “I’ve been a company woman all my life and look where it’s got me,” (p.304) says the older woman ruefully.

At the novel’s climax, the narrator is held hostage by Simellia, who is revealed to be working with the far-future agents. Our protagonist manages to turn the tables, damaging the time-door in a way which dispels the far-future threat, condemning the Brigadier to a grisly cosmic fate. Her efforts in turn affect Adela, who is no longer guaranteed to come about in the narrator’s timeline and ends up on an autopsy table: “[I]t looked like she exploded, but in reverse, and with light instead of viscera.” (p.324).

The narrator escapes the debacle of the novel’s denouement as a kind of bitter final gift; Simellia is blamed for the vandalism of the machine, and the narrator is let free on the basis that to do otherwise may damage the fragile timestream, as her fate is entwined with Adela’s. Gore, feeling betrayed by the narrator and Adela both, flees with Margaret, the other surviving expat.

After much time has passed, the narrator receives a photograph of distinctive Alaskan spruces, a glimpse of what is likely Margaret’s arm in shot, and a handwritten, partly crossed-out message: “Of course I loved you.” (p.329). (It’s piquant and pertinent, in a tale of temporal displacement and uncertainties, that the crossing-out changes the tense of the verb). In the final pages of the book, after reflecting on this photograph, the narrator declares that she is planning to take a trip.

The hopeful, unresolved note on which the novel concludes reminds us that “time can produce new social relations and even new forms of justice” (Freeman, 2010, p.48). Three figures, displaced, paradoxical, have the chance to cultivate intimacy and affection which go beyond convention. Yet this is also the British past living on, beyond the moment at which the time-door, now damaged, should even be capable of sustaining the expats’ territorial bodies.

As Freeman has it,

I thought the point of queer was to be always ahead of actually existing social possibilities […] Now I think the point may be to trail behind actually existing social possibilities: to be interested in the tail end of things, willing to be bathed in the fading light of whatever has been declared useless. (2010, p.13).

With the expats having become historical detritus and the Ministry of Time’s post-imperial project deemed a failure, new opportunities arrive at the “tail end of things.” The question of how the narrator, Gore, and Margaret will align, if they are fortunate enough to meet again, returns us to the matter of the novel’s queerness – with the narrator having expressed desire for both Gore and Margaret. One reading allows for a heterosexual pairing to lie beyond the novel’s final page, with Gore and the narrator pledged to one another in a conventional “happy ending.” Yet we have already seen what happens in the future where Adela and Gore pursued heteronormativity, monogamy, parenthood. Perhaps, Bradley’s novel quietly whispers in its final pages, something different will happen in the new timeline.

After all, once conventional temporality has been disrupted, “a hiccup in sequential time has the capacity to connect a group of people beyond monogamous, enduring couplehood” (Freeman, 2010, p.39).

Memories of the future, memories of empire

The narrator, making a different choice to her alternate self Adela, finds hope in her situation. This takes the form of a possible flight – to Alaska, where it appears, at the novel’s conclusion, that Gore and Margaret have fled.

Their freedom is not complete, requiring as it does a visit to yet another colonised territory. Bradley’s open-ended conclusion reminds us that there is nowhere outside the system of historical responsibility, even if diagonal moves can create new possibilities – just as Gore and the narrator were able to find love and mutual recognition as an oblique byproduct of the Ministry’s machinations.

It’s a usefully ambiguous final note to a book which is at once a sophisticated and unflinching interrogation of contemporary British identity and one which sits comfortably as a transatlantic bestseller, acclaimed by the culture it critiques. Yet, as Freeman notes, artworks may usefully “collect and remobilize archaic or futuristic debris as signs that things have been and could be otherwise. That capitalism can always reappropriate this form of time is no reason to end with despair” (2010, p.18). Bradley doesn’t shy away from the fraught, complex, compromised question of the narrator’s loyalties – to Gore, to her family, to her heritage, to Britain – or, indeed, those of her novel.

At the climactic gunpoint confrontation, the far-future agents’ co-conspirator, the Black British bridge Simellia, justifies her action in terms of the bodies from the “wrong” territories who did not merit rescue in the cruelties of the climate crisis:

“Two hundred years from now. It’s finished. South America’s mostly gone, except Brazil and its satellites. Half of Britain’s underwater. Europe dropped bombs on any ship in the Mediterranean coming from North Africa. No refugees. They died there or they turned back and died of disease and starvation and the heat. Billions died, billions.[“] (p.310)

The far-future ocean is once more the place of historic racialised migratory trauma recognised by contemporary critics like Sharpe (2016); when the narrator questions the veracity of this far-future account, Simellia is only sad: “How hard did you try to be a white girl that you’re asking me whether racism exists?” (p.310). Her understanding of the narrator’s romance with Gore is even less charitable:

“You let him off the hook again and again. I watched you. He came up through the Empire. He believed in it. And you did too. I read your file. The things that happened to your family. That’s why you joined up. Getting behind the biggest bully in the playground.” (p.311)

Bradley rejects easy answers, does not give the narrator any privileged retort. The sourest version of the thick present is on display: “The war won’t stop […] History will repeat itself, literally. The door means we just keep going back and forth, back and forth, again and again and again – ” (p.314). So far as the narrator has an answer, it is her attempted, abortive destruction of the time-door.

The novel thus refuses pat solutions, offering instead new iterations of the ambiguity under which all of us make decisions on our way to an uncertain future. Time-crossed lovers do not come to rest in each others’ arms, do not even guarantee to coincide again. There is only hope in the possibility of intersecting once more, outside of the confines of the time-travel project, and perhaps in a new configuration.

Conclusion: where next for the time-lost body?

Bradley’s novel leaves us on a path of ascent, however challenging, out of the lingering imperial mire. It uses the collision of past and future to open up ways of rethinking gendered and racialised bodies and minds.

This is important well beyond the field of science fiction criticism. In times of uncertainty, what we can imagine ahead of us matters. As Valenzuela and Lezaun have shown, visions such as “net zero” mobilise “active contestation not only over competing imaginaries of the future, but over what imagining a plausible climate future should mean in practice” (2024).

In the wake of the United Nations’ 2024 Pact for the Future, various governments are exploring legislation which obliges officials to take account of the needs of future generations. On the one hand, “there are reasons to anticipate real disruption in our current patterns of life, as we continue to see changes in the deep planetary systems on which life and society depend” (Sandford, 2023), what some commentators have called “the great unravelling” (Miller and Heinberg, 2023), and it is wise to act in anticipation. Yet it is very difficult to know what future generations will want or need or value, as they do not yet exist. It is hard to believe that civil servants tasked with such duties will avoid capture by whatever “officially plausible future” is designated by the powers that be (Finch, 2025). Part of what The Ministry of Time does is to remind us that what was considered a desirable future in the past – especially by those in power – might be quite different from what arrived, and that we may sometimes be grateful for this difference.

As the narrator puts it at the novel’s conclusion, revealing the book to be addressed to her past self:

I know how much you’ve longed for your future to lean down and cup your face, to whisper ‘don’t worry, it gets better‘. The truth is, it won’t get better if you keep making the same mistakes. It can get better, but you must allow yourself to imagine a world in which you are better. (p.331)

She discourages her past self against “believing yourself a node in a grand undertaking, that your past and your trauma will define your future, that individuals don’t matter. The most radical thing I ever did was love him, and I wasn’t even the first person in this story to do that.” (p.331). The narrator finally breaks with her lifelong attempt to keep safe by aligning her territorial body fully with the service of the state which welcomed her family from Cambodia. She steps away from imperial loyalty, and new possibilities open up by virtue of this, including two which are most vital:

Forgiveness, which takes you back to the person you were and lets you reset them. Hope, which exists in a future in which you are new. Forgiveness and hope are miracles. They let you change your life. They are time-travel. (p.331)

Simple truths, perhaps, but a simple truth is still a truth, and sometimes just the right tool to cut through all that is fraught, tangled, turbulent, and enmeshed with historical power. Bradley’s novel lays aside the stabilising comfort of “official” futures by demonstrating the nation-state’s continuity with its rapacious forebears. It proposes radical, oblique alternatives which do not erase the past but put diverse territorial bodies into new relations.

Freeman’s chronobiopolitics reminds us that “social change can be felt as well as cognitively apprehended” (2010, p.48) – and communicated through aesthetic forms. As a contribution to wider discussions of temporality and power, The Ministry of Time may help a broader public think differently about the future – showing how we can play with temporality in popular forms to think Britishness anew and think beyond Britishness, or national identity more generally.

Bradley, bringing to life a real-world Arctic explorer, fulfills Freeman’s “desire to enliven the dead and the understanding that this is never wholly possible” (2010, p.53). In doing so, she refuses jingoistic evocations of the imperial past – but allows for the possibility that this past might yet nourish something good in times to come. Her novel realises the “ethics of responsibility toward the other across time – toward the dead or toward that which was impossible in a given historical moment, each understood as calls for a different future to which we cannot but answer with imperfect and incomplete reparations” (Freeman, 2010, p.48). Bradley lets Gore, and the other, fictional, expats, and by extension, British territorial bodies more generally, move beyond the constraints of the past without effacing them.

A lot to ask of a bestselling science fiction romance? Perhaps not. We live in a time of broad science fiction literacy, when fantasies of time travel in popular culture have evolved beyond Wells’ mechanistic vision or even the period when Doc Brown had to carefully exposit parallel timelines with a chalkboard in Back to the Future II (1989).

In this, popular culture may be catching up with scholars of temporality, for whom a linear representation of time is only one framing, not always the most useful or even the most plausible; as Ramírez and Selin (2014) put it, with tongue in cheek, “For all we know in some situations the future is tetrahedral and in others it takes the form of a teddy bear.”

If we trade linear temporalities for the “thick present”, surrendering the separation of past and future, our actions may become a matter of “staying with the trouble” in Haraway’s sense: “learning to be truly present, not as a vanishing pivot between awful or edenic pasts and apocalyptic or salvific futures, but as mortal critters entwined in myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings.” (2016, p.1).

The viability of making this link via Bradley’s novel is evident in a flashback to the narrator’s childhood, almost perfectly aligned with Haraway’s notion:

When I was eight years old, I developed a keen awareness of the non-human world. Mai, Daddy, Sister, Home, School, Teacher, Bath, Plate, Chair, Crayon, Dress – these were not, as I had thought, the building blocks of the universe, but discrete entities in a world we shared with worms, mice, sparrows, woodlice, squirrels, moths, pigeons, cats, spiders. I had a wretched sense of fighting for space. They were everywhere, the non-human. They came from under things and out of shadows, they were higher than I could see in trees and deeper than I could penetrate in the soil […] A great, awful busyness was flourishing all around me. (p.142).

However fearfully, the narrator’s childhood self has recognised something which, in adulthood, she sought to suppress by accepting the authority of the state: our mutual critterhood in a thick present without hierarchy.

This lack of clear and hierarchical temporal logic is something which popular science fiction and its audiences are increasingly comfortable with. Cinema and television can now show us “everything everywhere all at once” (Kwan and Scheinert, 2023). In recent years, the big and small screen have given us temporalities that are “wibbly wobbly timey wimey” (“Blink”, Doctor Who, BBC, 2007) or whose trajectories resemble the arbitrary handwritten phrase “Jeremy Bearimy” (The Good Place, Fremulon, 2018), plus teen time travel movies which refuse unambiguous linear happy endings, surfacing the unspoken racial assumptions of Back to the Future and its ilk (See You Yesterday, 2019). In prose, we have El-Mohtar and Gladstone’s best-selling queer romance about rival agents interfering with time (2019), and Newitz (2019)’s depiction of time-travel interventions resembling a Wikipedia edit war between feminist “Daughters of Harriet” and incel-like male oppressors.

In this context, Bradley’s novel is not alone in reminding us: if the past, present, and future are no longer authoritatively singular, they may be retold and reshaped more widely and more wildly – not only by malign and oppressive forces, but also by those who seek to liberate territorial bodies wherever and whenever they are found.

Newitz’s work, with its right-wing American Men’s Rights Activist villains, is particularly resonant here in an era when some political forces seek to “rewrite the history of racial justice in the United States while eliminating the institutions that make visible its historical roots” (Giroux, 2020). In its antipatriarchal, queer, and antiracist stance, a punkier and more abrasive cousin to Bradley’s, Newitz’s book reminds us that the move towards a more diverse and disparate set of time-travel mechanics is also an opportunity for “decolonization” of the future (Ramírez and Wilkinson, 2014, p.47; Inayatullah, 1998), in the sense of shifting who speaks, who is heeded, and who is represented on its terrain.1

Time travel in science fiction has, itself, a history and prehistory, a present, and presumably a future. It has the potential for new and emergent ideas of temporality – scientific, poetic, popular, expert – to succeed those currently held by researchers, philosophers, artists, authors, critics, and the general public of the day.

An earlier era of time travel narrative experienced “fits and starts of […] types of fictional and scientific thinking” (Wittenberg, 2016, p.48), only some of which would lead on to the dominant paradigm of modernist time travel narratives. Perhaps Bradley’s novel will also, in times to come, show itself to be one of the works that opened the door onto a new era of popular time travel fiction. This new era is one which, however fraught, creates new opportunities for us to face up to the uncertainties around us, and within those uncertainties to rethink identity and temporality, just as Gore and the narrator find hope and promise beyond the limits of their novel’s final page, as eternally displaced persons.

REFERENCES

Bailey, F. and Bristol, S. (Writers) and Bristol, S. (Director). (2019). See you yesterday [Film]. Netflix.

Baran bo Odar (Executive Producer), & Jantje Friese (Executive Producer). (2017-2020). Dark [TV series]. Wiedemann & Berg Television.

Barthes, R. (1978). A lover’s discourse: Fragments. (R. Howard, Trans.). Hill and Wang.

Boym, S. (2001). The future of nostalgia. Basic Books.

Bradley, K. (2024). The Ministry of time. Hodder & Stoughton.

Dicks, T. and Hulke, M. (Writers) and Maloney, D. (Director). (1969). The war games. (Season 6) [TV series episode] in D. Sherwin (Producer), Doctor Who. BBC.

El-Mohtar, A., & Gladstone, M. (2019). This is how you lose the time war. Saga Press.

Finch, M. (2025). Looking beyond the ghost scenario. Issues in science and technology, XLI (3).

Finch, M. and Mahon, M. (2025). The ghosts we see from the mountains: scenario planning and the territorial body in time. In M. Sinclair and C. Spear (Eds.) Crisis and Body Politics in Twenty-First Century Cultural Production (pp. 162-180). Routledge.

Freeman, E. (2010). Time binds: Queer temporalities, queer histories. Duke University Press.

Gago, V. (2020). Feminist International: How To Change Everything. (G. Mason-Deese, Trans.) Verso.

Gago, V. and Mason-Deese, L. (2019). Rethinking situated knowledge from the perspective of Argentina’s feminist strike. Journal of Latin American Geography, 18(3).

Gale, B. (Writer) and Zemeckis, R. (Director). (1989). Back to the future part II. [Film].

Ghosh, A. (2016). The great derangement: Climate change and the unthinkable. Penguin.

Giroux, H. (2020). Trump aligns ignorance with bigotry as he attempts to rewrite history. The Conversation.

Halberstam, J. (2011). The queer art of failure. Duke University Press.

Hoyle, F. (1966). October the first is too late. Heinemann.

Inayatullah, S. (1998). Causal layered analysis: Poststructuralism as method. Futures, 30 (8).

Kwan, D., & Scheinert, D. (Directors/Writers). (2022). Everything everywhere all at once. [Film].

Leiber, F. (1961). The big time. Ace.

Lessing, D. (1982). The making of the representative for Planet 8. Alfred A. Knopf.

Miller, A. and Heinberg, R. (2023). Welcome to the great unravelling: Navigating the polycrisis of environmental and social breakdown. Post Carbon Institute.

Moffat, S. (Writer), and Macdonald, H. (Director). (2007, June 9). Blink (Season 3, Episode 10) [TV series episode]. In R. T. Davies (Executive Producer), Doctor Who. BBC Studios.

Muñoz, J. E. (2009). Cruising utopia: the then and there of queer futurity. New York University Press.

Newitz, A. (2019). The future of another timeline. Tor.

Priest, C. (1974). Inverted world. Faber and Faber.

Ramírez, R., & Selin, C. (2014). Plausibility and probability in scenario planning. Foresight, 16(1).

Ramírez, R. and Wilkinson, A. (2014). Strategic reframing: The Oxford scenario planning approach. Oxford University Press.

Roberts, A. (2014). A brief history of time-travel. In Bell, J. (ed.) Sci-fi: Days of fear and wonder. (pp. 40-44). BFI.

Russ, J. (1975). The female man. Bantam Books.

Sandford, R. (2023). Reparative futures in a thick, virtuous present. Futures, 154.

Schur, M. (Writer), and Goddard, D. (Director). (2018, October 18). Chapter 31: Jeremy Bearimy (Season 3, Episode 5) [TV series episode]. In M. Schur, D. Miner, M. Sackett, & D. Goddard (Executive Producers), The good place. Fremulon; 3 Arts Entertainment; Universal Television.

Sciamma, C. (Writer and director). (2023). Petite maman. [Film].

Sharpe, C. (2016). In the wake: on blackness and being. Duke University Press.

Sinclair, M., & Spear, C. (2025). Introduction: Territorial Bodies in Crisis. In Crisis and Body Politics in Twenty-First Century Cultural Production (pp.162-180).

Strugatsky, A., & Strugatsky, B. (1977). Roadside picnic. Macmillan.

Tuan, Y. (1977). Space and place: The perspective of experience. University of Minnesota Press.

Tuck, E. and Wayne Yang, K. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, education, & society. 1(1).

Valenzuela, J. M., and Lezaun, J. (2024). Publics and counter-publics of net-zero. Futures, 156.

Waldron, M. (Writer) and Raimi, S. (Director). (2022) Doctor Strange in the multiverse of madness. Marvel Studios.

Wittenberg, D. (2016). Time travel: The popular philosophy of narrative. Fordham University Press.

- Note, however, the caveat of Tuck and Yang (2012): “Decolonization brings about the repatriation of Indigenous land and life; it is not a metaphor for other things we want to do to improve our societies […] As important as their goals may be, social justice, critical methodologies, or approaches that decenter settler perspectives have objectives that may be incommensurable with decolonization. […] The metaphorization of decolonization makes possible a set of evasions, or “settler moves to innocence”, that problematically attempt to reconcile settler guilt and complicity, and rescue settler futurity.”

↩︎

§

Matt Finch, a writer and researcher, is an Associate Fellow at the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School and an Associate of the SexTechLab at the New School for Social Research. See more at mechanicaldolphin.com

One thought on “Eternally Displaced Persons? Territorial Bodies and The Ministry of Time”