Category: BSFA Review

Review: The Perfect Nine: The Epic of Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

Reviewed by Eugen Bacon. This review first appeared in The BSFA Review.

“Making things is a matter of hands and eyes.

All my daughters are makers of things.”

If you’ve read Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s fiction, comprising Wizard of the Crow, Petals of Blood, The River Between—some curriculum in African literature, seen his plays, like The Black Hermit, or read his essays and memoirs, you know to expect the unexpected. This preps you for his black speculative fiction The Perfect Nine: The Epic of Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi, on the founding of the nine clans of the Gĩkũyũ people of Kenya.

The verse narrative borrows from the mythology of Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi, the male and female forebearers created by the god of the mount, the giver supreme, the god of many names, also known as Mulungu, Unkulunku, Nyasai, Jok, Ngai, Yahweh, Allah. He/She is a unifying god, a being and nonbeing of distance and nearness, the here and there, the stars, moon and sun, the mother of the soil, water and wind. The giver grants Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi nine perfect daughters, and a tenth with a disability, and now the daughters have come of age.

In this mightily feminist story that blends folklore, mythology, adventure and allegory, translated from its original Gĩkũyũ version titled Kenda Mũiyũru(2018), the daughters are self-sufficient women who till the land, build their own huts, are self-reliant yet united in mind, heart and kinship.

There’s Wanjirũ, who put a curse on the hyena to smother greed. Wambũi, who rode a zebra to war, led an army to victory. Wanjikũ, who has a fierce love for personal freedom and self-reliance, and a healing power of peace. Wangũi, whose lullabies can dispel a war. Waithĩra, who resolves disputes with the wisdom of the mount. Njeri, whose power of glance is a quest for justice. Mwĩthaga, who can make rain. Wairimũ, who sculpts and invents life, can trap souls. Wangarĩ, whose courage of a leopard protects the powerless from the powerful. And Warigia, the unspoken tenth, born with a disability, but she charms animals, so much joy in her laughter, the whiteness of her teeth lights a path in the darkness, and her arrow never misses an eye.

Suitors arrive from far afield, lured by the silhouettes of the daughters’ beauty in their dreams, girls in fantasies who lead them down valleys to rivers with song. The suitors perform their own songs and dances of their regions, some picked up on the way, and they’re willing to serve the trinity of life—birth, life, death; the trinity of day—morn, noon and evening; the trinity of time—yesterday, today, tomorrow.

But with its caution on the lure of strangers, the cunning of ogres, the folly of greed and the ugliness of discord, the philosophical story tosses up challenges and much peril to the daughters and their ninety-nine suitors, until only the worthy remain.

With its inclusion of no distinction between man or woman, its inspiration on care of the land, its adages on the power of nature, and knowing to listen to the dictates of the heart, The Perfect Nineis an accomplished work that’s deeply cultural. It platforms the importance of naming in African tradition, the place of ceremony and the heart of kinship, bonded by blood or marriage—as one groom says to Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi:

“I want to talk to you, my father and my mother,” he said,

“For I cannot call you by any other name, given that

You received me and accepted me as your son.”

In this lush chronicle on the genesis of Gĩkũyũ clans through valour, family, nature and nurture, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o shows how supremely he’s a leading literary African author and scholar, a recipient of twelve honorary doctorates, and a nominee for the Man Booker International Prize.

“Life has and has not a beginning.

Life has and has not an end.

The beginning is the end and the end is the beginning.”

Review: Born of the Sun: Adventures in our Solar System edited by Mike Ashley

Reviewed by Graham Andrews. This review first appeared in The BSFA Review.

In Jack Williamson’s thought variant short story, ‘Born of the Sun’ (Astounding, March 1934), Sol – like possibly every other star in the universe – is a sentient being and the planets are its incubating eggs. Well, you can’t get much more “thought variant” than that! But since the Sun didn’t give birth by self-genesis, Mike Ashley has excluded it from his whistle-stop tour of the solar system. (I would have plumped for ‘The Golden Apples of the Sun’ – which is neither here, there, nor anywhere else.)

Ashley explains in his general introduction that the stories will deal with “the old solar system, beloved of writers of science fiction, before the space probes discovered what was really out there.” His Planetary Exclusion Order also applies to the Moon (but then he had placed Luna-set stories in the BL Moonrise: The Golden Age of Lunar Adventures anthology). Mars, however, could hardly have been left out of the batting order (see below). Following my usual form, I started by reading Ashley’s erudite* prologues before reading the actual stories.

*A redundant adjective, if ever there was one.

“So strap yourself in and prepare for a kaleidoscope of worlds!” (ibid.).

I’ll get the Golden Oldies – or at least Silveries – out of the way first. ‘Sunrise on Mercury’ (1957), by Robert Silverberg, takes place on the hot-side/twilight zone/cold-side innermost planet that we used to know and love so well. It’s one of his best early stories that never stops moving – or thinking. ‘Garden is the Void’ (1952) is Poul Anderson’s haunting exploration of an asteroid: “A green asteroid.” James Blish went over all Joycean again with ‘How Beautiful with Banners’ (1966), set on Titan, if not Saturn itself. Par example: “Feeling as naked as a peppermint soldier in his transparent film wrap, Dr. Ulla Hillstrom watched a flying cloak swirl away toward the black horizon with a certain consequent irony.” ‘Wait It Out’ (1968) is a marooned-on-Pluto story that shows how well Larry Niven could write hard science fictioon when he used to work at it. [And I, for one, will never accept Pluto as a ‘dwarf’ planet.] But my favourite classic story – and also my favourite story in the whole book – is Clifford Simak’s ‘Desertion’ (1944).

‘Desertion’ (1944). Set on and around Jupiter, it became an integral part of the fix-up novel City (1952) and inspired a crucial plot device in Avatar (watch and compare). The last four understated lines of this story never fail to move me. I envy anyone reading them for the first time.

As usual with Mike Ashley, however, it’s the little-known or even unknown stories by ditto authors that make these BL anthologies so worthwhile. Leslie F. Stone (1905-1991) was one of the “pioneer women” contributors to the dawn-age sf pulp magazines. She set ‘The Hell Planet’ (1932) on the “real” Vulcan, once thought to lie between Mercury and the Sun. Background reading: The Hunt for Vulcan (2015), by Thomas Levenson. ‘Foundling on Venus’ (1954) by John and Dorothy De Courcy has a stinging twist in the tale. John Ashcroft (1936-1997) does Mars proud with ‘The Lonely Path’ (1961). ‘Where No Man Walks’ (1952), by E. R. James (1920-2012), about mining for industrial diamonds on the “surface” of Uranus, could well have been expanded to novella, or even novel-length. It’s the strongest story in the book, in my opinion, after ‘Desertion’. By the same token, ‘A Baby on Neptune’, a collaboration between Claire Winger Harris (1891-1968) and Miles J. Breuer (1889-1945) is by far the worst story in the book. “Ye Gods!” shouted Kuwamoto. “Just at the crucial moment, like a cheap novel serial! I suppose all we can do is nothing, and Elzar’s child has been devoured by the filthy beast.”

It just remains for me to say that Born of the Sun is yet another excellent theme anthology edited by Mike Ashley for the British Library. Buy it! Read it! Keep it!

Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora

Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora. Edited by Zelda Knight and Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki

![Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora by [Zelda Knight, Marian Denise Moore, Eugen Bacon, Nicole Givens Kurtz, Dilman Dila, Rafeeat Aliyu, Suyi Davies Okungbowa, Michael Boatman, Odida Nyabundi, Ekpeki Oghenechovwe Donald]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51ykGGZ8LJL.jpg)

Reviewed by Fiona Moore

This review first appeared in The BSFA Review.

It’s become almost a cliché of conversations in sf circles: someone says that they would love to read more works by authors from non-Western, non-White, and/or postcolonial origins, but, they add, “I don’t really know where to start.” While the recent rise to prominence of African and African-diaspora authors like NK Jemisin, Nnedi Okorafor and Tade Thompson has been welcome, potential readers might still wonder where to look for writers in other sub-genres of sf, such as horror, Weird fiction, or post-apocalyptic fiction.

Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora provides a suitable answer to this question, being a sampler of a diverse range of stories by established African and African Diaspora authors, covering a startling range of genres that provides something for everyone. At the same time, however, there is plenty for those with a good understanding of Afrofuturism and Africanfuturism to appreciate.

All the stories were, however, at the very least interesting and in most cases very enjoyable to read. Some fit comfortably within familiar sf categorisations. “Trickin’”, by Nicole Givens Kurtz, is a Hallowe’en-set horror piece which develops both the vampire and demonic-possession subgenres. “Sleep, Papa, Sleep” by Suyi Okungbowa Davies is also on the conventional horror spectrum, a Lagos-set story involving necromancy and revenant corpses to explore family relationships. On the science fiction side, “Red_bati” by Dilman Dila, about a former robot pet now repurposed as a mining robot after the death of its human owner, fits into the growing genre of stories exploring the morality of creating AI for human use; this example does a good job of handling the balance between making the AI sympathetic and not obscuring his non-human mindset.

Other stories engage more directly with colonialism and postcolonialism. “A Maji Maji Chronicle” by Eugen Bacon is a fantasy about a mage who meddles with African colonial history, exploring questions about power, corruption and legitimate leadership. “To Say Nothing of Lost Figurines” by Rafeeat Aliyu is a mixed genre SF/fantasy, giving us a wizard from Earth tracking a magical object to an alien society and retrieving it with the aid of a half-human-half-alien woman. The idea of magic-as-science, a feature of much postcolonial sf including that from Africa and its diaspora, arises both as an embracing of the indigenous logics dismissed as superstition in a colonial context, and a challenge to the idea of “Western” science as hegemonic and objective. Here, it is counterpointed by the narrative of a mixed species character finding an escape from her oppressive birth society.

“The Unclean” by Nuzo Onoh is a genuinely terrifying horror fantasy about an Igbo woman in the 1950s in an abusive marriage; the best horror for me is always that which works as a metaphor for real-life issues, and the way in which the protagonist struggles against not just her husband and his family but the patriarchy of 1950s Nigeria in general is both reflected and amplified by the supernatural terrors she encounters (and sometimes brings into being herself). Mame Bougouma Diene’s “The Satellite Charmer” engages directly with Chinese neo-colonial activities in Africa, the background involves two Chinese mining companies using satellite technology for resource extraction in Senegal, our foreground is the life of one man, Ibrahima, affected by the satellites in unexpected ways and how he, and they, converge to an explosive meeting.

History, and more specifically the loss of (and recovery of) history, also emerges as a key theme. “A Mastery of German” by Marian Denise Moore is a near-future hard-science story whose protagonist is an American project manager tasked with evaluating (and possibly cancelling) a project meant to enable the transfer of human memory for profit; at the same time, we have the counter-narrative of the protagonist’s father attempting to trace the family history, thwarted by the invisibility of Black, enslaved and working-class people. The end result explores the meaning of individual and social memory not just in the USA, but any postcolonial country. “Emily,” also by Marian Denise Moore, is the shortest piece in the book, a poem starting with a historical advertisement for the return of an escaped enslaved girl and imagining different parallel futures for her, picking up on the theme of lost history in Moore’s earlier piece for the volume. “Thresher of Men” by Michael Boatman is a deeply satisfying revenge narrative: as a goddess takes vengeance on the White residents of an American town for past atrocities, we see the hidden history of the seemingly idyllic community emerge, beginning with a recent police shooting of a young Black man but going deeper into the past as the story unfolds, revealing the murder as one horror in a long chain of atrocities extending back decades, if not centuries.

Finally, some stories in this collection cross genres or defy classification. “Convergence In Chorus Architecture” by Dare Segun Falowo is a strange and surreal Weird fiction piece involving quests, boneships, human-arthropod fusions; the prose is beautiful and haunting and the imagery lingers. “Clanfall: Death of Kings” by Odida Nyabundi is a post-human post-apocalyptic adventure story, which reads like the setup to what could be a very interesting series, and one hopes the author develops this universe further. Finally, “Ife-Iyoku, The Tale of Imadeyunuagbon” by volume coeditor Ekpeki Oghenechovwe Donald tells the story of a society undone by its own essentialism; as the narrative twists and turns unexpectedly, so the story shifts genre, beginning as an epic heroic fantasy, before shifting into a postapocalyptic story with echoes of The Chrysalids, and shifting again into another divine revenge narrative.

Dominion is a worthy addition to volumes like Walking the Clouds and So Long Been Dreaming which serve as introductions to postcolonial and indigenous science fictions and fantasies. The interesting range of stories, genres and themes provides a clear guideline for people looking for new work by African and African Diaspora writers in their favourite subgenres. However, the exploration and development of themes of colonialism, history, and memory, as well as the re-interpretation of colonialist sf tropes such as vampires and AI through African and/or Afrofuturist lenses, means that the volume also contributes to the ongoing dialogue on decolonising science fiction.

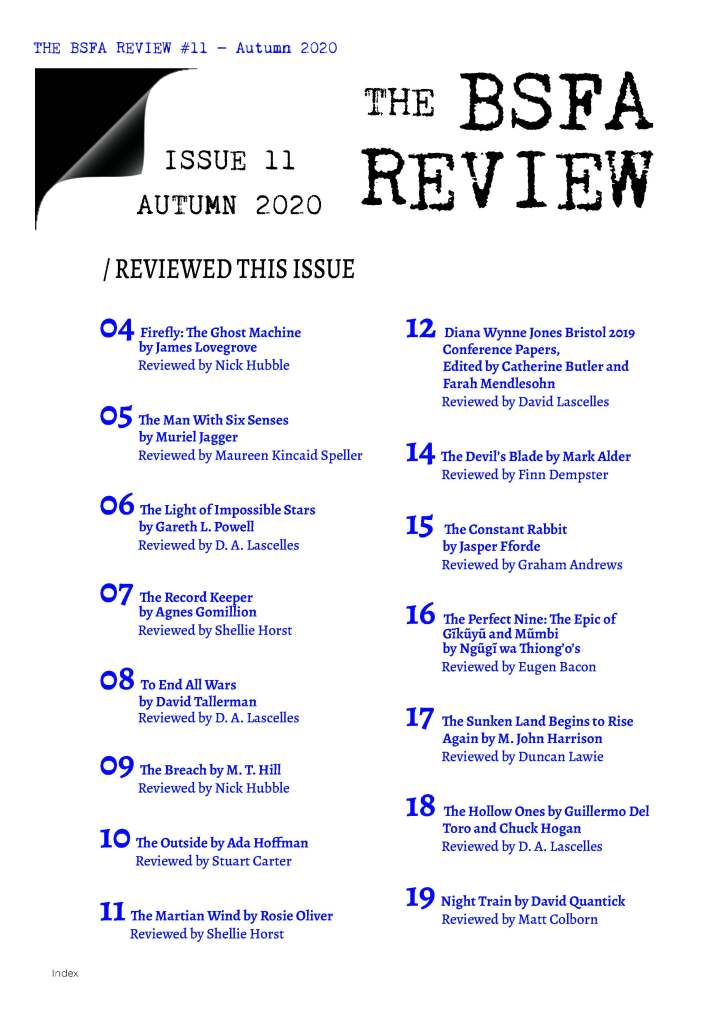

The BSFA Review Issue 11

The BSFA Review Issue 10

The BSFA Review Issue 9

The BSFA Review Issue 8

The BSFA Review Issue 7

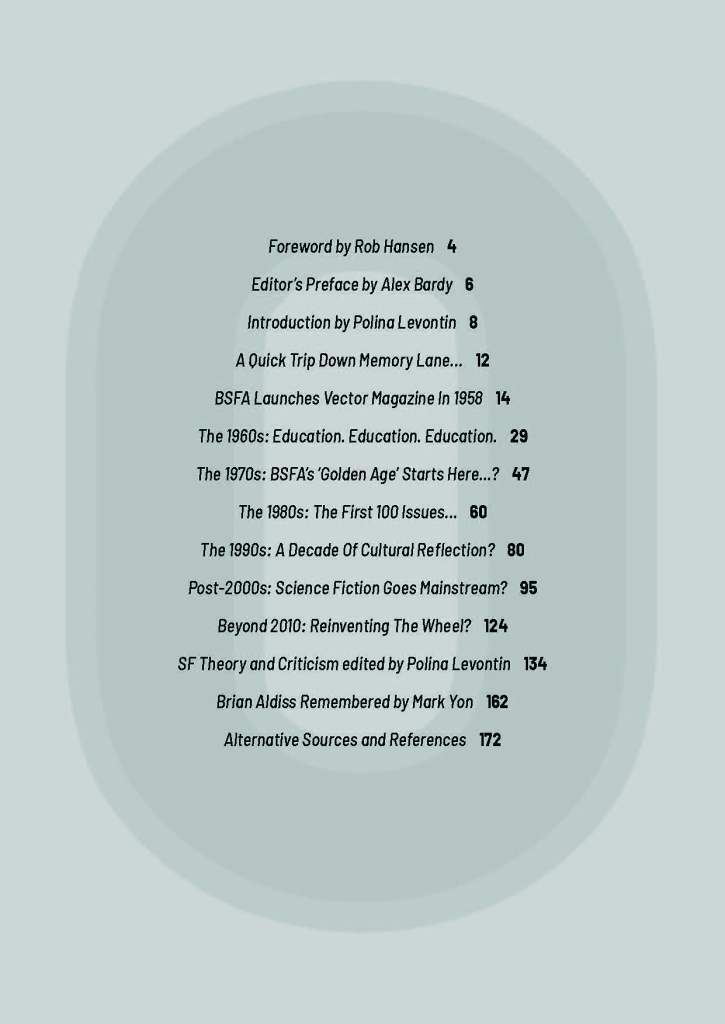

Through the Decades: Sixty Years of the BSFA

Edited by Alex Bardy. First published on behalf of the British Science Fiction Association, 2019.

Cover by Ian Long.