Category: Vector complete issues

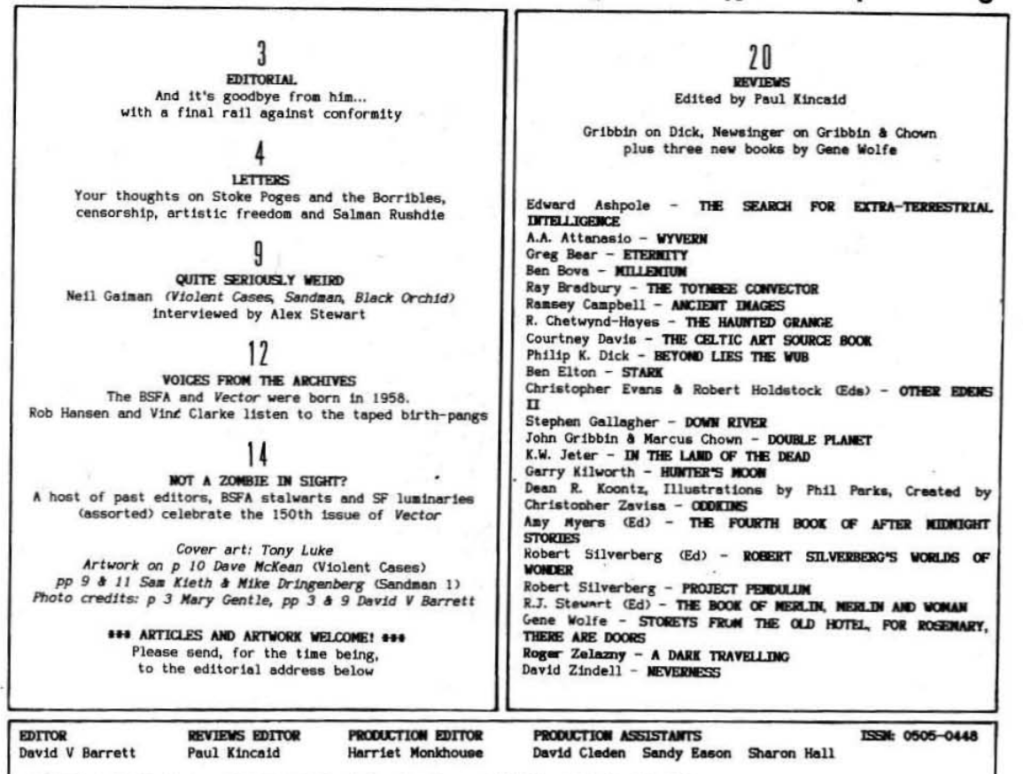

Vector #140

Why devote an issue of Vector to something many BSFA members said goodbye to years ago? Why should adults read something written for 10 year olds? Who is children’s SF actually written for? And why? Why should children read it? Does it have any value? Why should there be such a thing?

David V. Barrett

In writing SF, you try to achieve the shock of the new by inventing or distorting the world of your fiction. Children’s writers do not have to try with the externals, the readers’ inexperience is enough. The journey they must make is into their own past. But the technique is the same: a kind of cleaning of the needle — re-cognition of a world that is strange but also your own.

Gwyneth Jones

But the main thing I set out to do, at the start, was to break the two really restrictive old taboos. Taboo One stated that all adults, particularly parents, must be shown as wise, powerful, kind, understanding — in fact, faultless. Adults with faults were Baddies and had to be killed or reformed on the last page. Taboo Two permitted one child in each book to have one fault in order that he or she could be punished horribly, thus making the book Moral.

Diana Wynne Jones

So I decided to recognise this and treat every character of whatever age as a real person. The resulting freedom astonished me. The battle-line stopped seeming grim. I saw it as just a set of people with fears and foibles like anyone else. And there was no need to wonder what children wanted. I knew, since children are people too. I could write about the whole human race (ad any non-humans I cared to devise) and the only limit turned out to be that anyone reading the book has to be able to say, “Oh yes, we would react just like that!”

Diana Wynne Jones

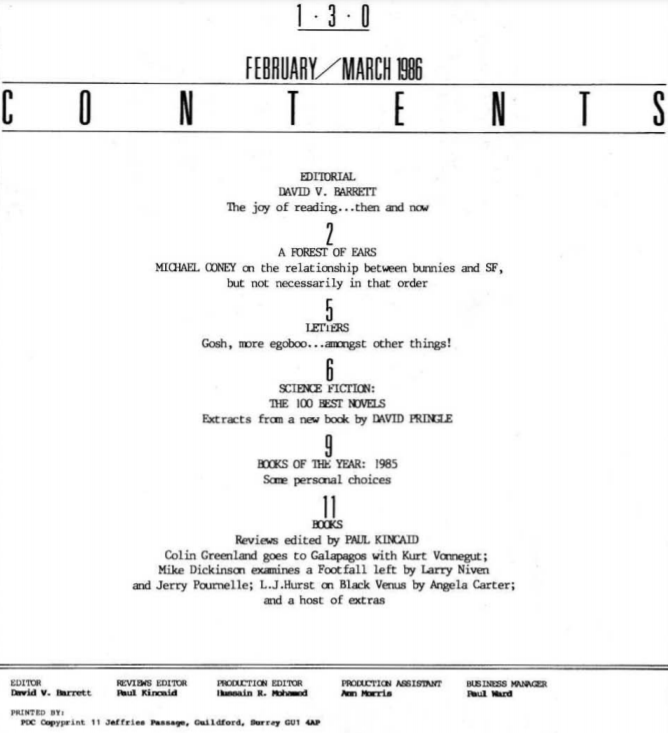

Vector #130

As writers we have the ability to create perfection, however: which may be another good reason for writing science fiction. From the biological standpoint we have a choice of two kinds of perfection: expanding or stable. The expanding kind postulates a dominant race, usually human, colonizing an ever-increasing number of worlds. There can be no end to the process of expansion because, like economic growth rates and the Roman Empire, the only alternative is collapse. Conflict is provided by the opposition of other races and such stories tend to be technological in content. An undeniable attraction lies in the headlong progression towards a vast Unknown, but the drawback is an uncomfortable similarity to our present situation on Earth.

I chose the second alternative for my recent novels because of its inherent optimism: it is theoretically possible to reach and sustain a stable perfection. The end product is a planet which a perfect ecology with a diversity of plants and animals dovetailing into a balanced whole. Conflict is provided by the arising of an occasional imbalance, either internally or externally inflicted. There is little room for technology in this kind of story because it would eventually be defeated by the finite nature of global resources, despite recycling and solar power. British SF often uses this introspective approach, although not always stating openly that life will go on after the difficult period that it often describes. Perhaps here there is an over-preoccupation with human life. The fact that the story is set at a point well before ecological stability is achieved sometimes brands it as ‘pessimistic’ in American eyes. This rather shortsighted view ignores the optimism inherent in the struggle for a stable perfection – as well as the practical impossibility of achieving an expanding perfection.

Michael Coney

Vector #120

Vector #110

I fervently hope that the attitude displayed by my previous article for Vector was not that of an embittered, ‘alf-arsed, unsuccessful, menopausal, hard-drinking, drug-taking, chaotic-rather-than-anarchistic, sexually frustrated, mixed-up-never-had-a-decent-teenage, half-and-self-educated, ivory-tower, fascist-middle-class-Bolshy-uptight-aggressive, dilettante, feminist, lesbian, Outsider, misfit, sour-grapes, never-even-had-a-slice-of-the-cake-never-mind-the-whole-bloody-cake, insufficient-self-sufficiency-freak, would-have-been-a-hippy-except-she-was-stuck-with-kids-on-a-housing-estate, been-through-the-mill-and-came-out-milled, doesn’t-give-a-fuck-about-the-proles, Hitler-must-have-been-okay-kids-and-animals-adored-him, talks-to-plants-they-are-the-only-people-who-understand-me, hide-her-head-in-the-sand-it’s-awful-out-there-and-my-bum’s-worth-viewing, apathetic, sit-on-the-fence, apolitical, mystical, nothin-better-to-do-than, why-doesn’t-she-get-a-decent-job, when-I’m-dead-‘they’-will-make-a-fortune, mere-self-indulgent-self-seeking-sensualist, pie-in-the-sky-dreamer, if-she’d-really-suffered-she-wouldn’t-have-time-for-all-that-psycho-surreal-crap, champion-of-lost-causes-better-lost, lives-in-her-own-world, put-on-dressed-as-sham, atavistic, anti-technology, unrealistic, pretentious, portentous, superior, writes-hairy-things-which-would-benefit-from-Occam’s-razor, obscurantist, Madame-Ovary-hides-again, can’t communicate-with-the-masses, thinks-the-world-owes-her-a-living, intellectual-bluestocking, dumb-woman-Chip-Delany-on-shoulder, penis-envying, message-carrying-nothing-relevant-to-say-really-writer sort of person, because, although all of the above descriptions have been made of me at one time or another, and many of them were, are or will be in some measure true, depending upon the point of view, none of them is all of the picture, but they also describe not only myself but all science fiction writers and readers. That above sentence incidentally is not my longest to date; I think the longest counted was 497 words counted by some angry reviewer with a short-attention span but time to count words who was delightfully misprinted as stating that one of my sentences contained ‘497 worlds’ — pretty good going for any science fiction writer. And the reason also for the fervent hopes at the beginning of this article is because, even if most of Science Fiction fandom either disclaims me or has never heard of me, I wish to be recognised as and am, one of the boys – er – sorry, club.

Josephine Saxon

Vector #103

So now ‘Towards A Critical Standard’ is complete, and forms a good bedrock basis for criticism. I must say that for me it had the effect of crystallising (and expanding) the method I try to employ in my own reviews. Any standard should be able to evaluate such diversities as, say, Dostoievsky, Le Guin, Iris Murdoch, John Norman and Barbara Cartland; and I think Muir’s categories might just cope. Still it is only a basis: I would like to see a standard that takes into account certain novels that break all the rules and still end up as good books. Criticism is to some degree a branch of pathology; the whole of a book is often greater than the sum of its autopsied parts.

And that, of course, while analysing the divisions of literature, leaves untouched the whole question of what books are ‘for’; and why anyone in their right mind should want to read 200-odd pages of total falsehood. A fiction is a lie: there is the paradox that a writer is a person who can only tell the truth by telling lies.

As a subpoint: does this mean that in future Vector might be reviewing books other than those published with the labels of SF and fantasy?

Still on criticism, and David Shotton’s point about slating any kind of serial or series: I think the main requirement is that (however many volumes it runs to) the sequence should have been conceived as a whole. There are obviously books that grow organically from the author’s previous works, like Eddison’s Zimiamvian fantasies and Donaldson’s new Covenant trilogy, but this is still legitimate. The objection is to interminable commercial follow-ups cashing in on the success of a first work — the Dune books, or the McCaffrey dragons, for example which were quite tolerable on their first appearance, but have since been diluted down to total bullshit. Commercialism isn’t a bad touchstone for hackwork.

Speaking of hackwork, I note that a certain Mr T Wogan has got his fangs into Carl Sagan’s Cosmos and the repeats of Blake’s 7. Is nothing sacred?

Mary Gentle

Vector #100

Vector #90

New Worlds (re the comments in your interview) was not aiming to take sf into the mainstream or move towards ‘personal’ (subjective technique as opposed to objective) fiction. We were hoping to borrow sf’s interest in the objective world and use that impulse in subtler ways. The U.S. ‘new wave’ was primarily a move towards subjective romanticism a la Pynchon, and I for one found this move depressing. Personal images are one thing. Writing about the self is another. VORTEX didn’t fail through lack of money – it failed through lack of faith and lack of professionalism. I heartily agree with you that new names are worthless in themselves unless they are connected with fresh ideas and talent. Asimov’s is building up a stable of hacks. It’s disappointing.

Michael Moorcock

Vector #80

Vector #70

What do we mean by violence? One might paraphrase Bertrand Russel: I am firm, you are aggressive, he is dangerously violent. One has to think in terms of some definition that means something to you that means something to me also. After all, we’re dealing with an[?] abstract noun. I really like abstract nouns, they’re very, very nice: they earn me money. Truth, beauty, honour, integrit, love – all abstract nouns. We now add violence. Good, let’s consider some concrete examples of violence; let’s bring the concept down from the realm of abstraction into the world of reality. One example of violence – let’s make it topical – an American airman in a plane over Vietnam. He presses a button at a given point, down goes the napalm, whether it’s the Vietcong who collect, whether it’s the Vietnamese who collect, it’s the people who collect. The result of pressing the button up there is violence, down there. Another example of violence, and, it seems to me, a rather different kind: a soldier with a fixed bayonet. He’s on a battlefield: his opponent is right in front of him, and with his fixed bayonet, he disembowells his opponent. He sees the blood and guts spill out.

[…]

There is a third kind of violence that one might consider – people will probably argue later. I think I’d describe it as ritual violence. In a repressive state, for example – you can argue about this later: Russia? South Africa? Greece? – the violence imposed by the state has a ritual attached to it. In a country where capital punishment exists, for example, and somebody commits a murder and gets the chop, that is also a form of ritual violence. But we also have milder examples of ritual violence nearer home – after all, what else is soccer, rugby, boxing, wrestling – a ritual violence. It’s one that has its own kind of codes, its own kind of rules, it’s indulged in as a sort of spectacle sport.

Edmund Cooper