Vector editors are supporting a workshop on applied SF at the University of Lagos as part of a larger collaboration with the African Speculative Fiction Society and Aké Arts & Book Festival.

If you are in Lagos, join us: www.africansfs.com/events

Vector editors are supporting a workshop on applied SF at the University of Lagos as part of a larger collaboration with the African Speculative Fiction Society and Aké Arts & Book Festival.

If you are in Lagos, join us: www.africansfs.com/events

Eve Smith is the author of three speculative thrillers. Her latest novel, ONE, published in 2023, is set in a one-child policy Britain that has been ravaged by climate change. It was longlisted for the 2023 British Science Fiction Association Best Novel award. Her debut, The Waiting Rooms, set during an antibiotic crisis, was shortlisted for the Bridport Prize First Novel Award and selected as a Guardian Book of the Month. Off Target, her second novel, imagines a world where genetic engineering of children has become the norm. It was a Times Book of the Month, who described it as ‘an astute, well-researched and convincing novel of ideas.’ Eve’s books are published by Orenda Books. Her website is www.evesmithauthor.com

Before writing full-time, Eve worked for an environmental charity on research projects across Asia, Africa and the Americas.

This interview developed out of an in-person event held at Ewell Library, UK, in September 2023.

Thanks for your time, Eve. Let’s start with ONE. It’s a chilling speculative thriller that covers many themes, from climate change to women’s rights. How did the novel come about and what was your process for writing it?

The premise for ONE was born out of two ideas. First, what if birth was a crime? How might a one-child policy play out in Britain? Second, how might the climate emergency change the UK, not only in terms of environmental impacts, but also the social and political ramifications? How would it affect how we’re governed and how we treat people?

During my research, I read Shen Yang’s More Than One Child, a powerful memoir about growing up as an illegal excess child in China under their one-child policy. The author had committed a crime just by being born. During China’s one-child policy over half a billion birth control procedures were carried out over more than three decades. Many of those sterilisations and terminations were forced. Given the recent abuses of abortion rights in the US, with Roe vs Wade being overturned, the fact that such a thing could happen today in a Western democracy made me question what else a government in the West might do to curtail reproductive rights.

In ONE, I also wanted to explore how a totalitarian party might take advantage of the climate crisis to secure power. In Europe, several far-right groups have adopted the clothes of an environmental agenda to promote nationalist policies. In my novel, on the surface, the UK appears to be doing pretty well. Through climate tech investment and radical shifts in policy and laws, the country has adapted to cope with many climate change effects. Britain is self-sufficient in food, water and energy. Jobs are plentiful. Healthcare is good. But it has come at a cost: freedom and choice.

Continue reading “Interview with Eve Smith”Andrew Merrie and Pat Keys in conversation with Jo Lindsay Walton (and briefly Polina Levontin) about science fiction prototyping and the Radical Ocean Futures project.

JW: We’re lucky enough to be joined by Andrew Merrie and Pat Keys. Andrew is a Research Liaison Officer at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University (Sweden) and the Head of Futures at Planethon. Pat is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State University (USA).

We want to find out more about your very intriguing Radical Ocean Futures project, and Science Fiction Prototyping in general—as well as adjacent ideas like applied science fiction, critical design fiction, diegetic prototyping, speculative design, all part of the theme of this special issue. But I guess let’s start with the high seas themselves. How do we define the high seas? What are some of the issues that arise in their governance? Surely mighty Poseidon is ungovernable? To me, those words already feel strange in a sentence together: ‘governing the high seas.’

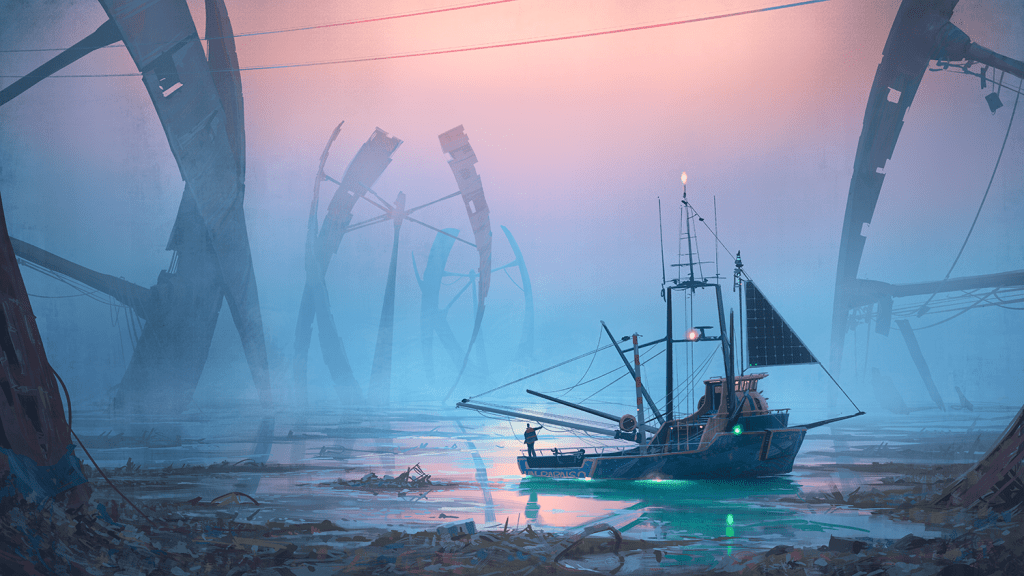

AM: The high seas are areas of the ocean that are not managed by any single authority. In some ways they represent this largely unexplored ‘wild west’ of the global ocean. When you’re trying to think about how to govern the high seas, you are thinking about things like climate change, overfishing, deep sea mining, genetic resources and so on. But you also have to contend with the pace of change. The ecosystems are changing, and the technology is changing, and companies and other kinds of actors can basically take advantage of these gaps or delays in regulation, and sort of do what they want in this ocean space. Interestingly enough, just a few weeks before this issue of Vector went live, a historic deal was made, after nearly 20 years of talks to put in place a legal framework, the UN High Seas Treaty. That said, monumental governance challenges remain and though very consequential, this is really the start of another 20 years of work.

JW: In this context, does ‘governance’ refer to international law?

AM: Partly. Governance is actually broader than that. It refers to a variety of laws, regulations, institutions, certifications, norms and so on. It’s everything that is relevant to how we look after the oceans, or fail to look after them. For example, for the governance of marine ecosystems, computer modelling is very important. But you can’t just look at a model and go, ‘OK, here is what will happen, if we follow this management strategy.’ There are all kinds of questions about what is possible or plausible. About what models to use, what their assumptions are, how you should interpret and use their outputs. All that could be part of governance.

JW: OK. And these questions are more than technical questions, right? They quickly get us into the realm of politics and ethics. But sticking with ocean ecology for a moment. Honestly, when I think of the ocean, I mostly think, ‘I have no idea what’s going on in there.’ I want to quote a 2016 WIRED article about your project. ‘Earth’s oceans are having a rough time right now. They’re oily, hot, acidic, full of dead fish—and their levels are rising.’ Can you tell us a bit more?

Continue reading “Adventures in Science Fiction Prototyping”Jo Lindsay Walton and Polina Levontin

Every issue of Vector is special, but this one is especially special. It is guest-edited by science fiction author Stephen Oram, and it was made possible through a collaboration between the British Science Fiction Association (BSFA), the UK’s oldest and largest association for writers, publishers and fans of science fiction1, and the Institute for Development Studies (IDS), an independent think tank affiliated with the University of Sussex.

The theme is ‘futures.’ Plural, obviously: science fiction would never be content with just one future. ‘Futures’ is also shorthand for ‘futures studies‘: horizon-scanning, strategic foresight, scenario planning, anticipatory governance, forecasting and backcasting, red teaming and wargaming, speculative design and diegetic prototyping, experiential futures, futures futures, superforecasting and plenty more besides.

When businesses, governments, financial institutions and other actors seek to peer into the future, they often use some variety of risk management. Risk management overlaps with futures studies, but it is really pretty distinct. As crystal balls go, it’s a prosaic one. It involves identifying risks, assessing (perhaps quantifying) them, monitoring them, and implementing treatment strategies (such as avoiding, reducing, sharing, transferring, or informed acceptance). There is even an International Standard for Risk Management (ISO 31000). By contrast, future studies is a field where the expert and the charlatan can be difficult to distinguish. Many futures practitioners may be unsure themselves which of these they are, or in what proportion they are both.

Continue reading “Vector ‘Futures’: Torque Control”