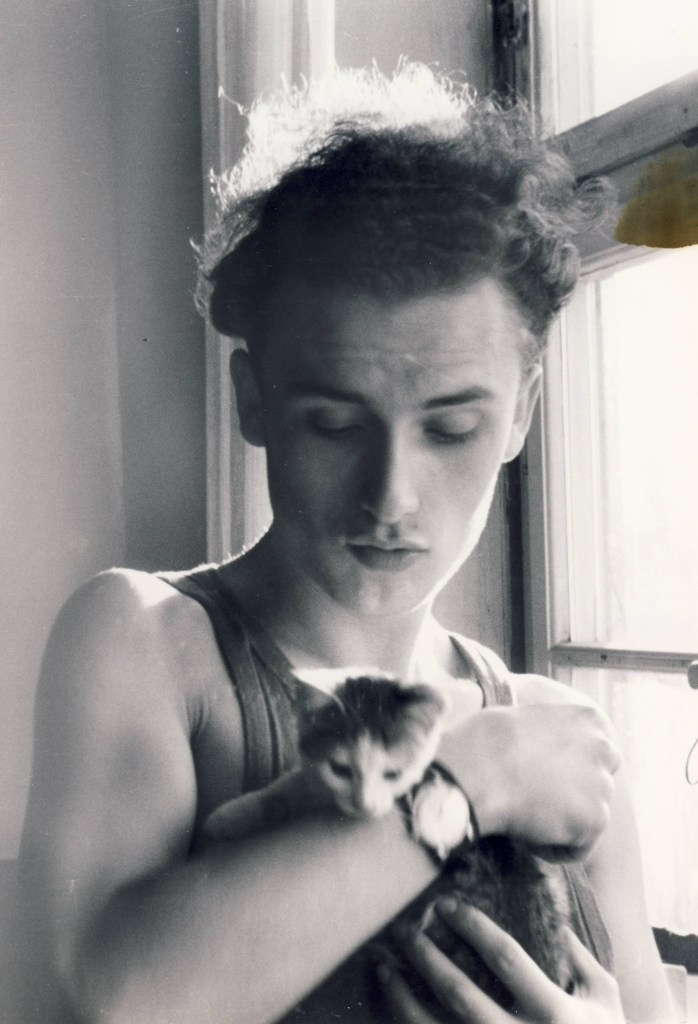

Adedapo Adeniyi (also goes by Dapo The Abstract) is a Nigerian artist working in literature, film and photography, music (DJ) as well as art curation and counterculture archiving. He expresses his art through abstract avant-garde sensibilities. His debut novel, Wanderer, is available in stores. You can read an excerpt of his novel below, courtesy of the author.

Chisom Umeh is a Nigerian fiction writer and poet. His short stories have been featured in Omenana, Apex, Clarkesworld, Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction 2023, African Ghosts anthology, Isele, Mythaxis, Scifi Shorts, and elsewhere. His short story, “Ancestor’s Gift”, won the 2024 Tractor Beam short story contest. He was a finalist for the Seattle Worldcon Short Story Contest and is the winner of the 2025 Nommo Award for Best African Speculative Fiction Short Story.

Chisom: Hey Dapo.

Nice to have you do the interview.

I finished reading your novel Wanderer a couple of days ago, and I must say, the journey feels like one long dream. It’s a steady flow of alternating sentences and logic that sometimes contradict each other and yet, strangely enough, feels complete and cohesive. Can you tell me how you were able to keep the story you were trying to tell in focus, even while spinning such a wild tale?

Dapo: Thank you, Chisom. I’m excited to have this interview with you.

I want to start by saying the story mostly wrote itself; I was just a conduit. Most of this book was written in an automatist, stream-of-consciousness style. They were retellings of dreams, memories, and reality, and I wanted them to appear that way. I never lost sight of the story because I welcomed getting lost as I was writing it to find myself.

Chisom: Oh, that’s pretty interesting. To me, the novel reads like Amos Tutuola’s The Palmwine Drinkard crossed with Vajra Chandrasekera’s luminous prose. It definitely felt like older hands were guiding yours on the page. Were there literary influences you were channeling when writing the book?

Dapo: Yeah, I mean, I try to stay away from direct influences while I’m writing, and I didn’t read The Palmwine Drinkard until after I wrote Wanderer. I took influences more from films and cinematic sensibilities than literary, but in that regard, Borges, Philip K. Dick, Timothy Leary, André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto, Aldous Huxley’s The Doors Of Perception, and my editor and friend, Manuel Marrero. I think these are the ones I can remember right now, plus I don’t want to go overboard. But these people and their works across surrealism, psychedelia, paranoid fiction, sci-fi, metafiction, and so on influenced me in many ways and were formative for how I approached writing and this book.

Chisom: It’s interesting that you mentioned Surrealist Manifesto, psychedelia, and paranoid fiction, because in an essay in Medium titled Abstractism Manifesto, you talked about how ‘abstractism’ is a term that subsumes all of these concepts and more. I like the way you explained it in the essay and how it relates to your work. But could you do a quick description of the term (abstractism) so we could understand it in relation to your work?

Dapo: Absolutely! So when I wrote the Abstractism Manifesto in early 2023, I defined it as being an amalgamation of solipsism, surrealism, psychedelia, subjective reality, and the physics of psychosis. I believe abstractism brings these concepts together to take reality and the world around us from a state of form to an abstract sensory state of formlessness, and that’s what I try to do with my work — the dissolution of some absolute real into an abstract cosmic real.

Chisom: In your experience as a filmmaker, what is the major difference between visual storytelling and written one? Do you prefer one medium over the other?

Dapo: I mean, writing is definitely cheaper. Making films is more expensive and taxing. I also think it’ll kill me faster so that might be why right now it excites me more than writing does. But, frankly, the major difference is the painting. With words, I’m guiding the readers’ imagination. At the end of the day, everyone will come out of it with different images. But with film, I have to literally represent those images on the screen. I’m doing the painting for the audience, they just have to watch and engage.

Chisom: Besides making movies, I know that you do some DJ work on the side. You had a collaboration with NTS, which is really great. How did that happen?

Dapo: Let me put it in context: I work with this new-age collective called Freewater, which was founded by my friends. I serve as its curator and co-director. Freewater secured a residency with NTS Radio, and since I also DJ, they featured one of my mixes as part of the collective. We’re having an underground, new wave music festival/concert on the 11th of December (I think the interview will be out after it?), and NTS is our major partner.

Chisom: That’s incredible, actually. So, does your music influence your writing in any way? Some writers like to curate playlists for particular writing projects. Something they listen to just to put themselves in the mood. Are you that kind of writer?

Dapo: Music definitely plays a huge part in my process. When I was writing Wanderer, all I listened to was shoegaze. I found a shoegaze playlist that had over a hundred songs and it was all I listened to while I slept and dreamt and while I wrote as well. I’ve been DJing for almost 2 years now, and it’s made me understand music as well as how different people interact with it. There are sensibilities of transience I borrowed from writing and translated to how I DJ.

Chisom: I kept wondering about the shoegaze reference when I was reading the book. Something told me there was more to it than just being an element in the story, and I’m glad you just confirmed that. Which brings me to your process with writing your stories and how you edit them. Do you edit while writing or after?

Dapo: Oh yeah, shoegaze has a very dreamlike, haze-inducing feeling and I wanted the book to feel like that. I do very minimal editing while writing. I finished the entire thing then read it over a couple of times before sending it to my editor, and we had this period of sending drafts back and forth and conversations on the subject matter.

But enough about me, I want to hear what type of music you listen to and how editing works for you. I mean, you just won the Nommo, haha.

Chisom: Oh, lol.

Well, I’m very mundane with my music. I don’t have any playlists or do any sort of curation. In fact, when I’m writing, I wouldn’t want to hear any music at all as it easily interferes with my thought processes and breaks my stream-of-consciousness, AKA “flow”. But when I do listen to music, outside writing, it’s very Davido and Asake and Victony, and whatever Dlala Thukzin just released. For edits, I can’t move forward with writing if I feel like there’s something wrong with a previous sentence. So I tinker with that till it feels fine to me. So we’re maybe kind of opposites on this.

Dapo: Correct me if I’m wrong but you seem like a very calculated writer. You’re delicate about detail, you’re careful. I think it’s beautiful. I wish I could be that type of writer. Like I said before (this may sound a little pretentious but I fully believe it), I don’t really do any writing, these things write themselves and use me as a conduit. I don’t know where they come from or where they are going or why; they come raw and I write in real time. My flow can be erratic most times.

Chisom: I like to think I have an eye for detail, but, trust me, I’m not really that meticulous. I know writers who would draw up elaborate plots that cover the first scene to the last, and fill up a board with sticky notes. Me? I mostly just sit down and write a story as it comes into my head. I think both our approaches are valid, so long as the outcome is something folks can read and enjoy. When I’m done writing and send the work out, that’s where my effort ends. But I’ve seen you go through hell and high water to publicize your book. And it has really paid off. Maybe that’s something you’d teach me someday?

Dapo: You’re amazing, so we’re kin.

Thank you, I think it’s been a learning curve. A lot of how this book has been handled is experimental, constantly trying to see how to reinvent whatever a rollout is supposed to be. Some days before the book came out I’d post videos of just my legs as I was walking around. Wandering, if you will. I made cards and handed out googly eyes. I’ve had readings and talks. I even had an abstractism lecture and played a psychedelic techno set. I keep thinking of ways to present a work of literature outside of just the confines of literature, especially as a multimedia artist. I look forward to reinterpreting the book and presenting it in so many other formats: photograph, sound, installation, you name it.

Chisom: Say I wanted to try my hand at writing abstractism, are you holding one of those lectures anytime soon?

Dapo: Hopefully sometime early next year. I’m working on writing another edition of the manifesto that’s more professional, but I think that through reading the manifesto that’s up right now, as well as Wanderer and some of my short stories, anyone could get the gist of what abstractism is.

What’s next for you now Chisom? In the world of African Speculative Fiction.

Chisom: For me, I’m also trying to piece together a collection of short stories that hopefully might be my debut in the book-publishing space. I want most of the stories in the collection to be centered around two themes, so that means I’m writing mostly new stories.

Anyway, it’s really been wonderful having this chat with you. I’m looking forward to reading more of your stuff in the future.

Dapo: Sending you love and the best of wishes Chisom, excited to see your collection. I’ll send you mine as it comes along. You’re a refreshing voice in the scene here.