The Faculty of Natural Sciences (FoNS) at Imperial College London held a speculative fiction contest on the subject of education in 2045. Here is the story that won first place.

The world is changing and there is little doubt that the future will be different from today, possibly profoundly.

In the face of these possible futures, what could this mean for education and for FoNS? What do we teach and how do we teach it? What is it like being a student or a lecturer here?

We invite you to join FoNS in the year 2045. What will you be doing? How will you be learning or teaching? We do not just want to hear about futuristic technologies or subject matter, nor do we want a purely dystopian vision. Instead, we invite you to write about what life is really like using those technologies or learning about relevant subjects in the context of a challenging world. Build us a world where we can look around and see the fabric of our faculty and university in all its detail.

www.imperial.ac.uk/natural-sciences/education-and-teaching/short-story-competition/

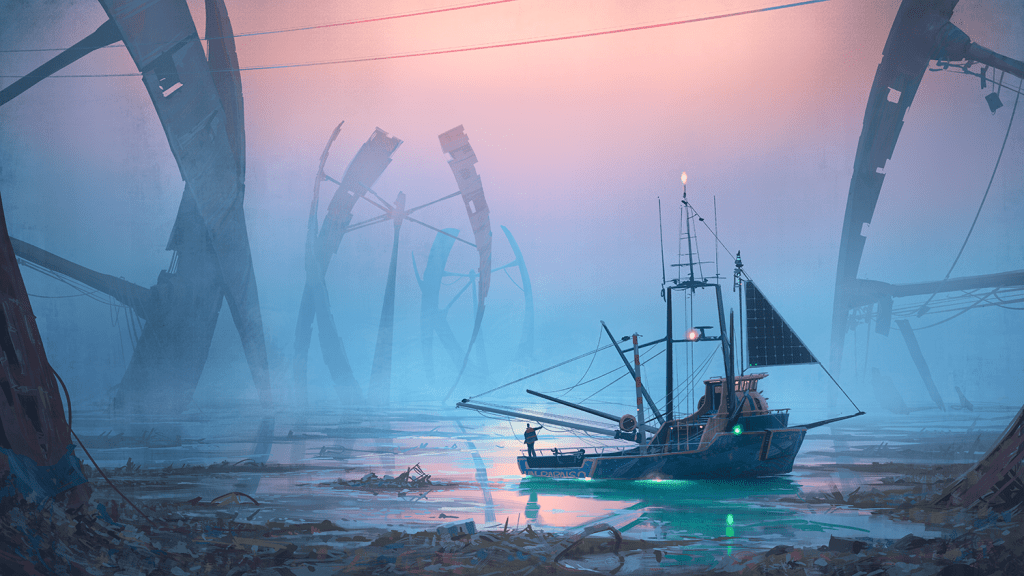

Wild Blue Yonder

By Daniel Hesk

I’m sat on the bench and I’m cold, and I’m tired, and here is what I can see:

1. The prim lawn, stretching off into the haze of dusk. An upswelling wind pulls a few leaves across the grass and mud towards me. My eyes water in the chill blast.

2. The tower, emerald dome still set afire by a sun which from my vantage has long since sunk into the ravenous outline of the library.

3. The statue, looking almost conventional from this angle. Lines of neon-red graffiti adorn its torso, too remote to read but I can guess at their essence. They must be recent, really recent – unmolested by caretakers or rainwater.

4. The grey buildings across the road, featureless in the dark, only two or three windows glowing. As I watch, a silhouette appears in the highest, backlit by bright fluorescence. It recedes after a second or two.

5. The sky, a pale azure turning to brilliant orange in the west. Something is unzipping it – over my head extends a lengthening streak of slate, diffuse at the back but hardening to a strict point at its end. There is a steady roar, like waves crashing somewhere far distant. Four turbines thrashing like crazy, modified fuselage churning out aerosol in immense volumes.

6. No stars. Not these days, thanks to our long and fruitful efforts.

When Leo arrives he approaches from my left and stands over me, grinning to hide his exhaustion. Two fingers tap behind his ears, and the implants are disabled. I ask him what he was listening to and the band he names sounds like a crossword clue. He calls me Al, because he finds it funny and he can’t pronounce Alparslan off the cuff.

‘Come on, Al,’ he says, ‘project time,’ He tries to take my hand.

‘Yeah,’ I respond, manoeuvring out of the way. ‘I know.’ I stand and stalk off towards the library. Unprepared for these English winters, I’m wearing just thin jeans and an Oxford shirt. The cold wraps around me. It burrows into my flesh. I imagine there might be frost tomorrow, emergent in the lee of buildings and bushes. I don’t think I’ve never seen frost before, not in my country, except maybe as a very young child. I have a vague memory of the fountain pool in our town square turning to ice, of the smooth and glittering surface like a mirror under my palm. Still, they say half your early memories are just subsequent inventions. I can’t trust myself to know.

In the library’s glass façade I see Leo following me. He’s dressed more sensibly than I am in a long, thick jacket. He fiddles with the lapel; I suspect he wants to shed the coat and drape it caringly over my shoulders. I walk a little faster and step gratefully indoors, sirocco air from the heaters a welcome relief. The rooms are largely empty, and I recognise many of the sparse occupants from our own course. Most degrees don’t set assignments this close to Christmas, but most degrees don’t have to justify their existence to the extent that Maths does. The department has been on death row for years, and they apparently feel that increasing the workload will present an image of vitality and necessity.

We find a spot on the fourth floor, by the western windows. The setting sun shines over the rooftops like a lighthouse from out across a black and frozen sea. Leo removes a silver rod from his pocket and fans it out into a screen and keyboard with a languid flick of his wrist. I try to ignore him and bring out my own laptop, firmly and consistently rectangular. It recognises my face and lights up, a picture of my parents frowning at a museum in İstanbul. I lean back in the chair until it starts to creak, and pull up the project. Spreadsheets and code, code and spreadsheets. Local Precipitation Effects of Marine Cloud Brightening, 2036-2039.

‘I can’t believe this,’ mutters Leo. ‘That we have to waste time on this crap.’ ‘Whatever. Just get on with it.’ I keep looking at the screen, but I hear him swing around to face me.

‘I mean, we’re supposed to be maths students, for god’s sake. I know it’s important, but there’s thirty other courses doing exactly this.’

I click my teeth together. ‘You realise that we are doing maths. You know, with the numbers and the sums and everything.’

‘Come on, you know what I mean.’

I do know what he means, unfortunately. My feet kick the ground and I rotate, not to look at him but back at the window. The sunset is unbelievably beautiful, a deepening bloodstain on the sky. The sulphur we’ve been pumping without end into the stratosphere has spread to every reach of the earth, making the Wild Blue Yonder that little bit whiter, making every evening shine that little bit more like burnished gold. They say you used the get the same effect after tests of nuclear weapons. The final formula for the aerosol was developed here, actually, at Imperial. It reflects enough heat to offset hundreds of thousands of times its weight in carbon dioxide. If you believe the press releases, it’s going to save the world.

Yes, we are the beating heart of progress. One of the last few universities in the UK, but we’re immune to the closures now. Practically every degree has turned its gaze towards the roiling, boiling planet, to the neglect of any other frontiers. Besides medicine, it’s the only

thing governments are willing or able to fund. There’s no time for any other pursuits. No time left at all.

‘Fifty people died in Kiribati last week.’ I say flatly. Leo pauses.

‘Yeah, I saw that. In Tuvalu or something…’

‘Tarawa.’ I still don’t look at him.

‘That’s it. Damn shame.’

‘A rogue wave took out the foundations of an emergency shelter. Whole thing just collapsed into the sea.’

‘Sure, tragic, but that’s not our fault.’ This now, this I laugh at. The sound of it rings with impertinence across the low-ceilinged space. From far behind me another student coughs, while a third drums their fingers on the table. In abject silence, noise can be contagious.

‘Of course it’s not our fault. By and large, it’s not the fault of anyone born this century. Still our planet though, isn’t it?’

‘Hmm.’ He folded his arms. ‘I think you’re looking at this wrong.’

Honestly, he’s a lot more tolerable when he’s arguing instead of flirting. ‘Go on, what do you think?’

‘You see Al, for me it’s about the principle…’

The sun disappears at last, and the starless sky presses down on the city like a bandage, like a hand.

***

I’m standing under a dark alder and I’m warm, and I’m tired, and here is what I can feel.

1. The rough bark behind me, uncompromisingly alive. My fingers trace its contours, the solid grooves slick with moisture and moss.

2. The leaf litter under my feet, crushed and crackling between bootheel and pavement. The little flakes carry their deaths with them, darting, dancing along the breeze.

3. The air, frigid and all too warm for this time of year. I sometimes imagine I can taste the changes in the wind, all the new and pervasive chemicals. What weaknesses we can find in the belly of the beast.

4. Leo’s coat across my shoulders. It’s heavy, and it smells of rain. I promised to return it tomorrow, and it’s a promise I intend to keep to the bastard. He left his gloves in the pockets and I play with the idea of pulling them on.

5. Hope, unexpected, maybe unwarranted. It wells up inside me and I exhale, my breath freezing instantly into a mist that swirls and drifts outwards into the night.

6. The world, spinning softly, dawn-bound, older than it has ever been before.

Inspired by my belief in the all-consuming severity of the climate crisis, and current theories of the geoengineering efforts that may have to be spearheaded by scientific institutions. I’m interested in how an increasingly singular focus for the natural sciences might be perceived, both in terms of its necessity and what other avenues might fall by the wayside amid such a pragmatic approach to research.

Daniel Hesk