Tag: jonathan mccalmont

Vector #274

- Torque Control (Vector 274) • [Torque Control] • essay by Shana Worthen

- Letter (Vector 274) • essay by Ian Massey

- Letter (Vector 274) • essay by Terry Jackman

- Letter (Vector 274) • essay by Tom Hunter

- Doctor By Doctor: Dr. Philip Boyce and Dr. Mark Piper in Star Trek … • essay by Victor Grech

- So Long, and Thanks for All the Visch: Douglas Adams and Doctor Snuggles • essay by Jacob Edwards

- Fishing for Time: Alternate Worlds in Nina Allan’s The Silver Wind and David Vann’s Legend of a Suicide • essay by David Hebblethwaite

- Bibliography: Law in Science Fiction • essay by Stephen Krueger

- Stark Adventuring: Leigh Brackett’s Tales of Eric John Stark • essay by Mike Barrett

- Joanne Hall Interviews Andy Bigwood • interview of Andy Bigwood • interview by Joanne Hall

- On the Colonisation of Nearby Stars • [Resonances] • essay by Stephen Baxter

- Sign of the Labrys by Margaret St. Clair • [Foundation Favourites] • essay by Andy Sawyer

- Songs of War • [Kincaid in Short] • essay by Paul Kincaid

- 2014 – A Year for Award-Winning Women? • [The BSFA Review] • essay by Martin Lewis

- Review: Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie • review by Gwyneth Jones

- Review: Throne of the Crescent Moon by Saladin Ahmed • review by Nic Clarke

- Review: Alif the Unseen by G. Willow Wilson • review by Nic Clarke

- Review: The Adjacent by Christopher Priest • review by Paul Kincaid

- Review: The Green Man by Kingsley Amis • review by Andy Sawyer

- Review: The Alteration by Kingsley Amis • review by Andy Sawyer

- Review: Benchmarks Continued: The F&SF “Books” Columns, Volume 1, 1975-1982 by Algis Budrys • review by Dan Hartland

- Review: Astounding Wonder: Imagining Science and Science Fiction in Interwar America by John Cheng • review by Paul Kincaid

- Review: Science Fiction by Mark Bould • review by Jonathan McCalmont

- Review: Vurt by Jeff Noon • review by Shaun Green

- Review: Pollen by Jeff Noon • review by Shaun Green

- Review: Mindjammer by Sarah Newton • review by Kate Onyett

- Review: Down to the Bone by Justina Robson • review by Patrick Mahon

- Review: Starship Seasons by Eric Brown • review by Ian Sales

- Review: The Devil’s Nebula by Eric Brown • review by Tony Jones

- Review: Helix Wars by Eric Brown • review by Tony Jones

- Review: The Mammoth Book of Time Travel SF by Mike Ashley • review by L. J. Hurst

- Review: The Shining Girls by Lauren Beukes • review by L. J. Hurst

- Review: Harvest of Time by Alastair Reynolds • review by Glyn Morgan

- Review: 11.22.63 by Stephen King • review by David Hebblethwaite

- Review: The Fictional Man by Al Ewing • review by Gary S. Dalkin [as by Gary Dalkin]

- Review: Seven Wonders by Adam Christopher • review by Jim Steel

- Review: Across the Event Horizon by Mercurio D. Rivera • review by Karen Burnham

- Review: After the End: Recent Apocalypses by Paula Guran • review by Stuart Carter

- Review: Nebula Awards Showcase 2013 by Catherine Asaro • review by Cherith Baldry

- Review: Fearsome Journeys by Jonathan Strahan • review by Anthony Nanson

- Review: Magic: An Anthology of the Esoteric and Arcane by Jonathan Oliver • review by Sandra Unerman

- Review: Tales of Majipoor by Robert Silverberg • review by L. J. Hurst

- Review: Savage City by Sophia McDougall • review by Maureen Kincaid Speller

- Review: Sharps by K. J. Parker • review by Liz Bourke

- Review: Fade to Black by Francis Knight • review by Lynne Bispham

- Review: The Heretic Land by Tim Lebbon • review by Gary S. Dalkin [as by Gary Dalkin]

- Review: The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There by Catherynne M. Valente • review by Sue Thomason

- Review: The Devil’s Apprentice by Jan Siegel • review by Anne F. Wilson

- Review: Rebellion by Lou Morgan • review by Kate Onyett

- Review: Angelfall by Susan Ee • review by Tony Jones

Vector #270

Vector 267

Go away for a week, and all sorts of things happen! Vector 267 arrived while I was traveling. Most people seem to have received their copies on Saturday, although a fair minority of those were partially soaked from the ongoing rains.

This quarter’s mailing includes, in addition to Vector, a booklet of Maureen Kincaid Speller’s writings, edited by Jonathan McCalmont and laid out by Martin McGrath.

This issue contains a broad assortment of intriguing and (I hope) thought-provoking content, including a few pieces, including Sam Mardon’s elegant cover, in honour of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Arthur C Clarke Award.

Matrix: A Magazine out of Time, Ian Whates

Introducing The BSFA Review, Martin Lewis

Sci-Fi London in 2011 in REview, Alys Sterling

Against Utopia: Arthur C Clarke and the Heterotopian Impulse

Homer’s Odyssey: The World’s First Fantasy Novel?, Juliet E McKenna

An Interview with Samuel R Delany, Roz Kaveney

Avatar: The New Fantastic Horizons of Oneiric Justice, Roberto Quaglia, trans. Teo Popescu

Kincaid in Short, Paul Kincaid

Now and Then, Terry Martin

Resonances, Stephen Baxter

Foundation Favourites, Andy Sawyer

The BSFA Review, edited by Martin Lewis

Reviews

The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction, edited by Mark Bould, Andrew M. Butler, Adam Roberts and Sheryl Vint (Routledge, 2009) – Reviewed by Glyn Morgan

The Mervyn Stone Mysteries: Geek Tragedy, DVD Extras Include: Murder and Cursed Among Sequels by Nev Fountain (Big Finish, 2010) – Reviewed by Gary Dalkin

Sci-Fi London Film Festival: Dinoshark (2010), Sharktopus (2010), One Hundred Mornings (2009), Zenith (2010), Gantz (2011) and Super (2010) – Reviewed by Martin McGrath

Ignition City, written by Warren Ellis and illustrated by Gianluca Pagliarani (Avatar, 2010) – Reviewed by James Bacon

Twin Spica: Volume 1 by Kou Yaginuma (Vertical, 2010) – Reviewed by Nick Honeywell

Mardock Scramble by Tow Ubukata, translated by Edwin Hawkes (Haikasoru, 2011) – Reviewed by Alan Fraser

Gantz (2011) – Reviewed by Lalith Vipulananthan

Under Heaven by Guy Gavriel Kay (Harper Voyager, 2010) – Reviewed by Dan Hartland

The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi (Orbit, 2010) – Reviewed by Andy Sawyer

On Stranger Tides by Tim Powers (Corvus, 2011) – Reviewed by Paul Kincaid

The Broken Kingdoms by NK Jemisin (Orbit, 2010) – Reviewed by Sandra Unerman

The Dragon’s Path by Daniel Abraham (Orbit, 2011) – Reviewed by Sue Thomason

The Heroes by Joe Abercrombie (Gollancz, 2011) – Reviewed by Maureen Kincaid Speller

The Scarab Path by Adrian Tchaikovsky (Tor, 2010) – Reviewed by Nic Clarke

The Wolf Age by James Enge (Pyr, 2010) – Reviewed by A.P. Canavan

Blood and Iron by Tony Ballantyne (Tor, 2010) – Reviewed by David Towsey

The Evolutionary Void by Peter F Hamilton (Pan MacMillan, 2010) – Reviewed by Martin Potts

Point by Thomas Blackthorne (Angry Robot, 2011) – Reviewed by Alan Fraser

Embedded by Dan Abnett (Angry Robot, 2011) – Reviewed by Stuart Carter

Vector welcomes letters of comment, or feedback on the forum.

Vector 266

Vector 266 arrived with the post yesterday, along with Focus and Quantum, an occasional BSFA newsletter. It’s real, it’s approximately on time, and it might inadvertently convince recent BSFA members that Vector comes out slightly more often than it does, coming so soon on the heels of the previous issue. Really, the journal is still quarterly.

This is the 2010 year-in-review issue, featuring retrospectives on the novels, television shows, and movies of 2011, along with an article on Stephen Lawhead’s Pendragon cycle, and two new column. One, (previously in Matrix) is from Terry Martin of Murky Depths. The second, “Kincaid in Short” from Paul Kincaid, is on Kate Wilhelm’s “The Infinity Box” and, bafflingly, we collectively managed to omit it from the Table of Contents, so it’s particularly important you know it’s there, starting on p. 34.

As long as I’m providing corrections: the version below includes Jonathan McCalmont’s name correctly spelled, and, where page numbers are provided, corrections to those too.

It’s also the first issue I’ve edited.

A Year in Review, Martin Lewis

2010: Books in Review, Vector reviewers

2010: Television in Review, Alison Page

2010: Film in Review, Jonathan McCalmont

Strip Club: A Fanciful Flight, Terry Martin

The Promise and Pitfalls of Christian Agenda in Stephen Lawhead’s Pendragon Cycle, Anthony Nanson

Foundation’s Favourites: Scholars and Soldiers, Andy Sawyer

Resonances: Alpha Centauri, Stephen Baxter (p. 32)

Kincaid in Short: “The Infinity Box”, Paul Kincaid (p. 34)

First Impressions, edited by Martin Lewis (p. 37)

I’ll post the full list of books reviewed in a week or two, when our review’s editor is back from holiday.

Vector welcomes letters of comment, or feedback on the forum.

Vector #266

3 • Torque Control • editorial by Shana Worthen

4 • A Year in Review: Looking Back at 2010 • essay by Martin Lewis

5 • 2010: Books in Review • essay by Graham Andrews and Lynne Bispham and Mark Connorton and Gary Dalkin and Alan Fraser and Niall Harrison and David Hebblethwaite and Tony Keen and Paul Kincaid and Jonathan McCalmont and Martin McGrath and Anthony Nanson and Martin Potts and Paul Graham Raven and Ian Sales and Jim Steel and Martyn Taylor and Sandra Unnerman and Anne Wilson

15 • 2010: Television in Review • essay by Alison Page

20 • 2010 in Film: Not My Kind of Genre • essay by Jonathan McCalmont

24 • Strip Club: A Fanciful Flight • essay by Terry Martin

26 • The Promises and Pitfalls of a Christian Agenda in Stephen Lawhead’s Pendragon Cycle • essay by Anthony Nanson

30 • Scholars and Soldiers • [Foundation Favourites • 12] • essay by Andy Sawyer

32 • Alpha Centauri • [Resonances • 61] • essay by Stephen Baxter

34 • Kincaid in Short • [Kincaid in Short] • essay by Paul Kincaid

37 • Review: Finch by Jeff VanderMeer • review by Paul Graham Raven

38 • Review: Lightborn by Tricia Sullivan • review by Jonathan McCalmont

39 • Review: Surface Detail by Iain M. Banks • review by Marcus Flavin

40 • Review: The Technician by Neal Asher • review by Stuart Carter

40 • Review: Version 43 by Philip Palmer • review by David Hebblethwaite

41 • Review: How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe by Charles Yu • review by Martin McGrath

41 • Review: Galileo’s Dream by Kim Stanley Robinson • review by Anthony Nanson

42 • Review: Music for Another World by Mark Harding • review by Dave M. Roberts

42 • Review: The Immersion Book of SF by Carmelo Rafala • review by Maureen Kincaid Speller

43 • Review: Zombie: An Anthology of the Undead by Christopher Golden • review by Colin B. Harvey [as by C. B. Harvey]

43 • Review: The Loving Dead by Amelia Beamer • review by Niall Harrison

44 • Review: Feed by Mira Grant • review by Alex Williams

44 • Review: Tomes of the Dead: Anno Mortis by Rebecca Levene • review by Shaun Green

45 • Review: Songs of the Dying Earth by Gardner Dozois and George R. R. Martin • review by L. J. Hurst

46 • Review: The Black Prism by Brent Weeks • review by Donna Scott

46 • Review: The Fallen Blade by Jon Courtenay Grimwood • review by Anne F. Wilson

47 • Review: Animal Alterity: Science Fiction and the Question of the Animal by Sherryl Vint • review by Gwyneth Jones

[Mary] Gentle’s prose is sharp, her powers of invention brilliant, her characters real, especially the greasy, obese Casaubon with his pet rat. They are not necessarily likeable. Casaubon is a Lord, and not on Our Side (there’s a neat scene where he’s confronted with the woman who does his laundry who has to live on far less than the cost of one single garment), and when Valentine re-appears a couple of novels down the line she does a dreadful and unforgivable thing. But, in the best tradition of the malcontents in the Jacobean drama, boy, are they vivid! This was a new thing.

For a time I used the word scholarpunk for this fusion of erudition and bad-ass attitude. Fortunately no-one noticed.

Andy Sawyer

Nowhere was this tiredness more evident than in the lugubriously self-indulgent Iron Man 2. Jon Favreau’s Iron Man (2008) was something of an unexpected hit; its combination of clever casting and pseudo-political posturing caught the public’s imagination while its lighter tone and aspirational Californian setting served as a useful counterpoint to the doom and gloom of Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight (2008). However, the second Robert Downey Jr.’s Tony Stark steps on stage in the sequel, it is obvious that something is terribly wrong. The film’s onanistic triumphalism and bare-faced declaration that social ills are best confronted by private sector moral entrepreneurs feels astonishingly ugly and politically insensitive at a time when private sector entrepreneurs are having their companies propped-up at the expense of the poor and the hungry. The decision to cast Mickey Rourke as a shambling Russian baddy is laughably pretentious in a film that ultimately boils down to a bunch of computer-generated robots punching each other in the face for about an hour.

Jonathan McCalmont

I found a Darwin site where a respondent asked “who else thinks Beatrix Potter may have developed her stories, about animals with increasingly human characteristics, from acquaintance with Darwin’s theory?” The idea that Beatrix Potter had to wait for The Origin Of Species before she thought of writing about reprobate foxes, trusting piglets, thieving magpies and insolent rats may seem ridiculous but this internetgeneration query is revealing. Our animal folklore is no longer refreshed by experience. In my own lifetime, here in the UK, the estrangement that began as soon as agriculture was established, has accelerated almost to vanishing point. We see animals as pets; as entertainment products we consume through the screen (where their fate, nowadays, holds a tragic fascination). We see them, perhaps, as an increasingly problematic food source. We no longer ‘meet their gaze’ as independent neighbours. The neo-Darwinists have even been doing their damnedest to break the link that Charles Darwin forged, when he transformed our deep intuition of continuity with the animal world into ‘scientific fact’.

Gwyneth Jones

And was Karel Čapek really writing about newts?

Gwyneth Jones

On the whole, however, Vint does a good job of disentangling “the animal” from the mix and Animal Alterity is an impressive achievement. A study of this kind isn’t meant to offer solutions and there are none (beyond a rather vague promise that post-humanism will blur the line between human and animal). Instead there’s a mass of evidence identifying sf as a resource: a treasury for Animal Studies academics; a rich means of bringing those moral arguments to life —drawn from an overlooked genre that has (always, already) developed sophisticated ways of thinking about looming problems that have only just occurred to the mainstream.

To the general reader, Animal Alterity offers food for thought and a quirky compendium of offbeat and classic titles. Could a “related book” on this topic become widely popular? I don’t know. In my day, sf fans tended to be petrol-headed meat-munchers, their concern for our stewardship of the ecosphere constrained by a passion for beer, mayhem and go-faster starships. Times have changed. The younger generation may feel very differently: I hope so.

Gwyneth Jones

Vector 265

Saturday morning’s post brought with it Vector 265, at long last. Not just Vector: the mailing includes a booklet in memory of Rob Holstock, edited by Niall Harrison; the BSFA Awards booklet, with all of the shortlisted short stories; and a ballot for voting on the BSFA awards.

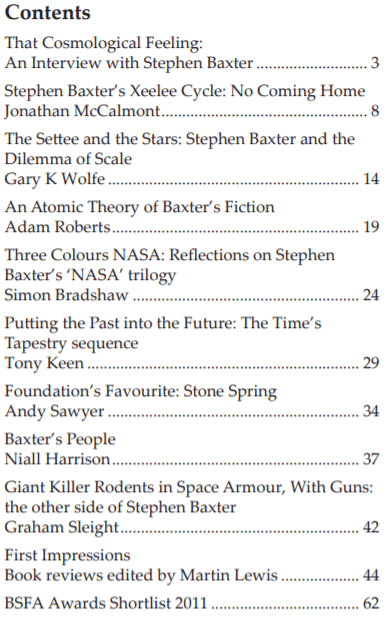

Vector 265 is the last one edited by Niall, and it’s a hefty one, a rich tribute to Stephen Baxter, plus book reviews, edited by Martin Lewis. For those of you not currently BSFA members, here is what you’re missing out on:

Table of Contents

“That Cosmological Feeling: An Interview with Stephen Baxter”

“Stephen Baxter’s Xeelee Cycle: No Coming Home”, Jonathan McCalmont

“The Settee and the Stars: Stephen Baxter and the Dilemma of Scale”, Gary K Wolfe

“An Atomic Theory of Baxter’s Fiction”, Adam Roberts

“Three Colours NASA: Reflections on Stephen Baxter’s ‘NASA’ trilogy”, Simon Bradshaw

“Putting the Past into the Future: The Time’s Tapestry sequence”, Tony Keen

“Foundation’s Favourite: Stone Spring”, Andy Sawyer

“Baxter’s People”, Niall Harrison

“Giant Killer Rodents in Space Armour, With Guns: the other side of Stephen Baxter”, Graham Sleight

“First Impressions”, Martin Lewis

Book reviews edited by Martin Lewis

Orgasmachine by Ian Watson (Newcon Press, 2010) – reviewed by

Justin Robson

Shine, edited by Jetse de Vries (Solaris, 2010) – reviewed by

Anthony Nanson

The Quantum Thief by Hannu Rajaniemi (Gollancz, 2010) –

reviewed by Paul Kincaid

The Dervish House by Ian McDonald (Gollancz, 2010) – reviewed

by Tony Keen

The Restoration Game by Ken MacLeod (Orbit, 2010) – reviewed by

Michael Abbott

The Fuller Memorandum by Charles Stross (Orbit, 2010) –

reviewed by Martin Potts

Escape From Hell by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle (Tor, 2009)

– reviewed by Dave M Roberts

The Turing Test by Chris Beckett and The Last Reef by

Gareth L Powell (Elastic Press, 2008) – reviewed by Dave M Roberts

The Holy Machine (Corvus, 2010) and Marcher (Cosmos

Books, 2008) by Chris Beckett – reviewed by Jim Steel

Inside/Outside – Chris Beckett interviewed by Paul Graham Raven

Major Carnage by Gord Zajac (ChiZine Publications, 2010) –

reviewed by Shaun Green

Nexus: Ascension by Robert Boyczuk (ChiZine Pubications, 2010)

– reviewed by Graham Andrews

The Nemesis List by RJ Frith – reviewed by Ben Jeapes

The Noise Within by Ian Whates (Solaris, 2010) – reviewed by

Stuart Carter

Brave Story and The Book Of Heroes by Miyuke Miyabe

(Haikasoru, 2007 and 2009) – reviewed by Cherith Baldry

WE by John Dickinson (David Fickling Books, 2010) – reviewed by

Donna Scott

I Am Number Four by Pittacus Lore (Penguin, 2010) – reviewed by CB Harvey

Monsters Of Men by Patrick Ness (Walker Books, 2010) – reviewed

by Anne F Wilson

The Iron Hunt, Darkness Calls and A Wild Light by

Marjorie M Liu (Orbit, 2008-10) – reviewed by Amanda Rutter

The Poison Throne by Celine Kiernan (Orbit, 2009) – reviewed by

Alan Fraser

Shadow Prowler by Alexey Pehov (Simon & Schuster, 2010) –

reviewed by Sandra Unerman

The Office Of Shadow by Mathew Sturges (Pyr, 2010) – reviewed

by AP Canavan

Lord Of The Changing Winds by Rachel Neumeier (Orbit, 2010) –

reviewed by Lynne Bispham

BSFA Awards Shortlist 2011

Anyone who joined the BSFA recently may end up with the wrong impression as to how frequently mailings occur, inasmuch as we expect the next one to be sent out within the next month-or-so. It’s all still quarterly, however.

Vector welcomes letters of comment, or feedback on the forum.

Vector #265

This revolution in production and distribution gives us, the reader, unfettered access to filth but it also allows publishers to print ultra-niche products and still find an audience.

Martin Lewis, ‘First Impressions: The Book Review Column’

A Discussion about Matter, part three

A quick recap, using Paul’s snappy titles:

And now at Velcro City Tourist Board:

Jonathan: It occurred to me a while back that ideology seems to have drained out of SF. Heinlein’s works may have essentially became fora in which he could appear as an appropriately father-like Mary Sue and then mouth off about whatever political issue was getting his goat at the time, but I think that nowadays genre is struggling to keep in touch with the idea of people being genuinely politically motivated.

The Culture books are weird in that they’re frequently political but the politics aren’t particularly fine-grained. The result is that you have characters working for SC out of a genuine desire to further the political aims of SC but as those aims are frequently unclear, the politics serve quite poorly as character motivation, merely resulting in lots of people being enigmatic and secretive.

Note: Links redirected to Internet Archive February 2021.

A Discussion about Matter, part two

As promised, here’s the second installment of that discussion about Iain M Banks’ new book, Matter. Part one is here, and part three will be over at the Velcro City Tourist Board tomorrow. Enjoy!

Niall: And so to question three, the big one: what did you think of Matter?

Jonathan: Matter put me in mind of that Helix column by John Barnes where he argued that all artistic movements and genres passing through three phases. You have the initial phase when ideas are laid down, then the second phase when you get the great masters of the genre and then the third phase when it’s all about being a virtuoso, about not challenging the limits of your genre but rather producing art that relentlessly pursues beauty as defined by the genre with no interest in innovation or change.

In those terms, Matter is not just a virtuoso work of SF, it’s also a virtuoso Culture book.

The previous three Culture books were more “difficult” because rather than following the formula laid down by the early Culture novels, Banks went out of his way to examine the Culture from new perspectives. Matter has no difficulty. In fact, it’s probably the most accessible Culture novel since The Player of Games. The concepts in it are all familiar and were developed in previous books, a lot of the characters are familiar and really there’s nothing new in it. It’s just a well constructed Culture novel. There are neat character arcs, big plot lines and quests for those readers who want escapism. Matter will probably be one of the most commercially successful Culture books ever written.

However, I couldn’t help but feel that Banks has just stopped trying to be clever and has settled down into a commercially successful franchise that will doubtless keep him in single malts and Porsche Boxters until the end of his days. His fans will adore the book, as will most SF fans looking for a bit of adventure with some witty remarks but personally, I thought Matter was disappointing in its complete lack of ambition.

James: I thought Matter was disappointing, and not just in lack of ambition, but more generally. Maybe it was my expectations? To me it read like an overlong fantasy epic, and when it finally got going it ended. I want to see more Culture, not the societies they’re messing with, or the aliens they’re sharing the galaxy with. I want Minds, Ships, SC. Culture stuff. Basically, I want Excession.

I also thought it was far too long. Banks was obviously having fun with his mega-BDO and pretending to be a fantasy writer, but I got bored. Compare that to something as huge as the Night’s Dawn Trilogy, where whatever else you want to say about it I can’t remember ever being bored. It crossed my mind that maybe Banks was suffering from the JK Rowling syndrome of being too succesful to be edited.

Niall: Overlong fantasy epic? No, no, that was The Algebraist!

More seriously, space opera and epic fantasy are one of the points on the literary spectrum where sf and fantasy come closest to each other (and then mingle, in Star Wars), so I can see where you’re coming from. But in Matter it didn’t bother me, largely because the characters on Sursamen know full well they’re not living in a fantasy world. They know they’re in a giant artificial world, they know there are vastly more advanced species above them, and they have to deal with that.

So I enjoyed it. I have to say I didn’t even find it overlong; big, yes, but not padded. I read it in a much shorter timeframe than most of you, which probably gives me a different perspective, but on the level of basic reading pleasure it kept me fully engaged – it was fun, often funny, sometimes dazzling, with a couple of proper emotional punches towards the end. What I think Matter adds to the Culture series as a whole is a much clearer sense than there has been before of (a) how the different species in the galaxy are trapped into a hierarchy and (b) what it’s like for them to try to live within that hierarchy. And many-levelled Sursamen is of course the perfect setting for literalising those ideas.

James: Yeah, I do agree with some of what you’re saying Niall. I’m pretty sure a lot of my disappointment was down to my expectations. I agree with your last point about what Matter adds, and there were definitely enjoyable parts – witty bits that made me laugh, cool mega-tech etc. But by the end I was left thinking “what was all that actually about?” There seemed lots of, not so much padding, but meandering away from the plot; quite literally in the case of some of the characters.

Paul: I enjoyed Matter very much, possibly because I came to it with no prior expectations beyond it being a Banks novel set in the Culture universe. Which may sound counter-intuitive, as that’s exactly what seems to have disappointed others, but it may clarify if I say I read Banks for the way he writes as much as the what he writes.

Granted, I’d have been pretty stoked if we’d had another Excession-scale Minds’n’conspiracies fest, or a Use of Weapons literary effort. But what we have instead is something that seemed pretty inevitable (and was clarified in the interview) – it’s the edges where things happen in a stable society like the Culture, and that’s where Banks’ thinking has shifted to.

If anything, as a function of the above, I think Matter‘s flaw is that it is unconsciously pitched to readers familiar with the franchise more than to the newcomer – though not in a cynical way, just in the same way that any franchise universe becomes self-contained and slightly exclusive over time, not least in part because its creator becomes so attached to (and familiar with) it.

I’d agree that Matter meandered – but that’s not a flaw for me, Banks meanders in a way I enjoy. And I’ll agree there were loose threads (a function of that stated deliberate effort to make it seem like the start of a trilogy even though it isn’t one?) – but again, that’s not an issue, as I think similar loose threads of plot are what has filled in much of the fine grain detail of the Culture universe over the years.

I think what we’re highlighting here is indeed how expectations and mind-sets make a book different to different readers. I’ve been accused of being a forgiving reviewer before (in music as well as books), and it’s a fair cop. I try to look for the best in things if I can, that’s just my way, though I try as best as possible to leave predisposition to the side. On the other end of the scale, we have Jonathan, who subscribes to the “test-to-destruction” method – setting the highest of standards for everything without favour or compromise, a position I often wish I could emulate (not least because it comes across as a lot less wishy-washy than my own).

I can see all the things that have been pointed out as flaws in Matter, and noticed them while reading it too (I have the post-its to prove it!). But the simple fact is I just enjoyed reading it. A metaphor for this phenomenon just occurred to me, but it’s a trifle earthy and colourful and deals with the fairer sex, so I’ll let your imaginations do the work …

Final point – Jonathan’s accusation of a lack of ambition is one that could be made to stick, I think, but only in one sense. Banks certainly had no ambition to further the field of space opera, or of sf in general. But I think there’s a case to be made that he has tried to do something different and ambitious within the field of Culture novels. Determining its success or failure on its own terms would take being privy to the man’s inner creative processes – which he either doesn’t examine (as he claims) or guards like a junk-yard dog. So, we have to let the reading public (and us critics, natch) decide its worth on whatever terms we bring to the table, I guess … and it appears mine are unfussy!

Niall: It’s interesting that you talk about Matter being pitched to readers familiar with the franchise because if anything, I got the opposite vibe – I couldn’t shake the feeling that this was a Culture novel intended as an introduction to the Culture for those readers, primarily US readers, who may not have encountered it before. It’s quite true that this could be another result of expectation on my part. After all, I knew before I started reading it that (a) Banks hasn’t had huge success in the US, historically, and (b) Orbit are planning to make a fuss about the US launch of Matter – but it meant that I read some of the digressions as cluing-in-the-newbies rather than self-indulgent-wandering.

Jonathan: Yes, I’d agree with all of that.

I think that Matter is a work of little artistic ambition but some quite considerable commercial ambition. I know it’s generally considered a bit “off” to speculate about author’s mindsets but if this book wasn’t written with the explicit intension of “cracking” America then I’d be very much surprised.

This leads us to my first question: How did people feel about the plotting?

I thought that the individual plot threads worked on a tactical level but failed on a strategic level. What I mean by this is that the arcs associated with all of the characters worked well in and of themselves. You had the young Prince having to work out what politics was all about, you had the older prince realising that the world he inhabits really is incalculably larger than the courtly dances and bawdy houses he frequents, and you had the SC agent juggling the ethical and practical demands of the Culture (her adopted culture) and of her native culture. So you had Need For Vengeance vs. Career Management and Non-Intervention Vs. Using Your Culture Training To Go Home And Kick Arse.

I thought all of these threads were well written and nicely handled but they made little or no sense as parts of a larger story. The older Prince escaped from the Shellworld and went off to find an ally who delivered a speech and sent him home. The younger prince learned some politics but it didn’t make a difference in the end since he never got to rule, and the SC person was completely passive, just turning up and watching some other stuff going on.

Furthermore I felt that, even by the standards of the Culture novels, the plot with aliens wanting to kill some other alien was all a bit convoluted and silly.

I got the impression that Banks was mining the Big Book of fantasy plot lines – wrangling tropes effectively but with little real attention given to the wider political issues that tended to characterise the previous Culture novels, which would all have little threads going on but they’d all fit into a wider picture. Matter has no wider picture… just pleasing little stories that are nicely unchallenging and unadventurous.

Paul: Points taken, Niall – another perspective issue. I dunno, I just figured if he was going to do a “Culture 101”, there’s be a lot more close detail set within the core Culture, a la The Player of Games, Excession etc. But again, we’re assuming conscious agency where the man claims there was none, so we’ll never get a definite answer, I suspect.

Niall: I have to think he was being just a little disingenuous when he said that to Farah – I mean, I’m willing to believe he’s a pretty instinctive writer, but I do find it hard to imagine writing any novel, and certainly not one this big, without at least some idea of what I want to say and who I want to say it to. On the other hand, I’m of the school of thought that says that everything on the page is the result of a writerly choice, on the grounds that if we want to hold them responsible for some of it (either to praise or to criticise) we have to hold them responsible for all of it, even if the choice is not always an excruciatingly concious and thought-through one.

Back to the plots … as Paul alluded to, in his BSFA interview Banks also said he wrote the book to feel like part one of a trilogy, with no intention of ever writing parts two and three. I think he succeeded entirely in that goal, but if you’re not prepared to roll with that – the realisation, about 80% of the way through, that the book you’re reading is not the book you thought you were reading – it’s going to be unsatisfying, because of the way various plots either change direction suddenly or end up unfinished. On the other hand, if you do roll with it it’s a nice inversion.

In the case of Oramen, I disagree with Jonathan’s assessment; I thought the fact that, in the end, his journey didn’t go anywhere was tragic in the best sense. (It helps that I was starting to worry, at that point, that the whole book would be irredeemably cosy, and that none of the protagonists would get seriously hurt.) In the other two cases, I think Jonathan has a point, and in particular the length of Anaplian’s journey did feel contrived to make sure she was in the right place at just the right time.

More broadly, I think you could make a case that plot and character end up subservient to idea and theme. For me the book was so strongly about hierarchy and differing ideas of what power and freedom mean at different points in a hierarchy that I could certainly see someone making that case against the book. (Which means I’m not sure I can go along with your argument that the book has no wider picture.) But then, most of the time when I was reading Matter I was quite happy to be swept up in the development of the idea.

Jonathan: Fair enough Niall, in that case I think that we should address the “wider message” once we’ve all had a go with the plot.

James: Niall, I don’t agree with you about intent – I often think that critics over-analyse work, and found it quite amusing when Farah analysed Banks’ writing and he more or less said, I don’t know, that’s your job. (And at this point, if you haven’t already guessed, I should point out that I’m not a critic in any sense, as my reviews on BDO will reveal!) I’m not exactly in the same league as Banks (understatement) but I have definitely written stories that just come out, writing in the headlights as it were. Admittedly when writing a novel the length of time it takes often leads to deeper thought, but surely the writer can just aim for a “good story”?

On plots, I pretty much agree with Jonathan. Everything was setup in the first few chapters, and I was feeling optimistic, and then everything just bumbled along until the very end, when everyone died. Everyone went on a journey somewhere, during which nothing much happened of importance. And everything seemed subservient to the shellworld. It reminded me of Rendezvous With Rama, or Ringworld in this aspect, both of which I found dreadfully dull.

And then there’s the monster under the falls! What was that all about? It came from nowhere and just tried to kill everyone. Why? Because it was nasty and wanted to kill Shellworlds. I didn’t like it at all, and By the end I was left wondering what had really happened? Was the whole big picture just random? Did anyone really know what the monster under the falls was? Did the higher level Involveds really care? It all felt so unresolved. The plot for me was the worst aspect of the book.

Paul: Well, I think saying it (they) were bad would be a stretch too far, but they weren’t the stars of the show either. I agree with James that there are a lot of unresolved threads (though not as many as all that – I seem to remember some signposting about the critter beneath the falls earlier on, a remnant of one of the various factions of species that vie for control of the shellworlds, IIRC). But again, we’re back to the “false trilogy” issue – which means there was very possibly a deliberate attempt to make the situation seem wider and more complex than it would actually be shown to be.

I think the analogy here is that Matter, if it were a film, spent more production time on the CGI and eyeball kicks than it did on translating the story as conceived into the story displayed, if you see what I mean. It’s the ‘blockbuster’ phase of the Culture oeuvre, perhaps. But again, I think the unoriginality of plot threads is probably meant to be subservient to the wider theme. The theme is the engine, the plots are the roads the vehicle drives upon.

Note: Link to Part 1 redirected to Internet Archive in Feb 2021. Part III is also in the Archive.