By Dilman Dila

Last year, after a long wait, I got a chance to see Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s Naked Reality, which he describes as an afrofuturistic/sci-fi. Shot in black and white, it is a time-travel tale in which the protagonist searches for her identity, this being allegorical for a continent’s search for its identity. Like his earlier films, including Les Saignantes (2005), it does not use visual effects or mise-en-scène to portray the future. But while strong storytelling with an offbeat style carried his previous works, Naked Reality turned out to be difficult to watch. Its website suggests it “is a new science-fiction interactive and collaborative cinema concept where we make feature films with a story as usual but take out certain aspects like sets, music, dialogues, costumes…” While there is a call for collaboration, it is not clear if it would mean re-editing this film. What made it drag was the miming, the near complete lack of sets, and the attempt to compensate using overlays, where two video clips are blended together – kind of the cinematographic equivalent of Instagram filters – creating a style more suitable to music videos. If ten years ago a lack of props or effects could be a consequence of low budget, today, more resources are available to a filmmaker, especially in a collaborative venture, and there is free software to achieve photorealistic visual effects.

One such software is Unity. In 2016, the company behind it made a short film, Adam (available on YouTube), to showcase its cinematic creation tools and to test out the graphical quality achievable. Adam is short and sweet to look at, though does not have much of a story. The main protagonist, a prisoner, wakes up in a robot’s body along with scores of others. They meet a mystical figure, who leads them away into a bleak horizon. In 2017, Unity partnered with Neill Blomkamp – the South African director well-known for District 9 – to make two sequels to Adam, where we learn of a government called The Consortium, which harvests the body parts of prisoners but, rather than kill them, puts their brains in robots, for unknown but possibly legal or even mercantile reasons. I like the series so far, and although both plot and character development are still thin, it is a visual joy.

Neill will be making more episodes of Adam alongside other short films in his own Oats Studios, which he set up to develop ideas without years of waiting for Hollywood. The first film he made was Rakka, set in a dystopian, post alien-invasion world. The obsession of seeing aliens as the evil other echoes colonialist era fears (e.g. H.G Well’s War of the Worlds) but also resonates with anti-immigration sentiments of today. Rakka features Sigourney Weaver, whose great performance failed to save the film from a clichéd plot that does not add anything new to an alien invasion narrative.

I thought other Oats Studios films would be similar, but was pleasantly surprised. Firebase starts off like an alien-contact film, and ends up something like a revenge-ghost story, with US soldiers in Vietnam encountering something called the River God. Like the other shorts from Oats Studios, Firebase could develop into a feature film, and a recent tweet from Neill suggests he is planning to crowdfund its production – this might explain its abrupt and unresolved ending.

Zygote is the film I liked the most. Though it also seems to be the first twenty minutes of a feature, it works beautifully as a stand-alone short. It’s a sick horror, a good old-fashioned monster tale redolent of Frankenstein, and it may be difficult for some people to watch. I liked the monster very much because it reminded me of Amos Tutuola’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, and the awesome “flash-eyed mother,” which is a ghost made up of “millions of heads which were just like a baby’s head,” each with two hands and two eyes that shone day and night. Zygote gripped me right from the start, and the suspense did not relent. It is set in an asteroid mining operation, and the story opens with two survivors from a catastrophe that is never fully explained, though we deduce it coincided with the creation of the monster. One survivor is a slave, an orphan bought in her infancy, and the other a synthetic human, who sacrifices himself to help the orphan escape. Like most of Neil’s films, this one is very entertaining, and yet still packs in social issues, in this case genetic engineering and a critique of corporate capitalism.

Zygote is the film I liked the most. Though it also seems to be the first twenty minutes of a feature, it works beautifully as a stand-alone short. It’s a sick horror, a good old-fashioned monster tale redolent of Frankenstein, and it may be difficult for some people to watch. I liked the monster very much because it reminded me of Amos Tutuola’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, and the awesome “flash-eyed mother,” which is a ghost made up of “millions of heads which were just like a baby’s head,” each with two hands and two eyes that shone day and night. Zygote gripped me right from the start, and the suspense did not relent. It is set in an asteroid mining operation, and the story opens with two survivors from a catastrophe that is never fully explained, though we deduce it coincided with the creation of the monster. One survivor is a slave, an orphan bought in her infancy, and the other a synthetic human, who sacrifices himself to help the orphan escape. Like most of Neil’s films, this one is very entertaining, and yet still packs in social issues, in this case genetic engineering and a critique of corporate capitalism.

By

By

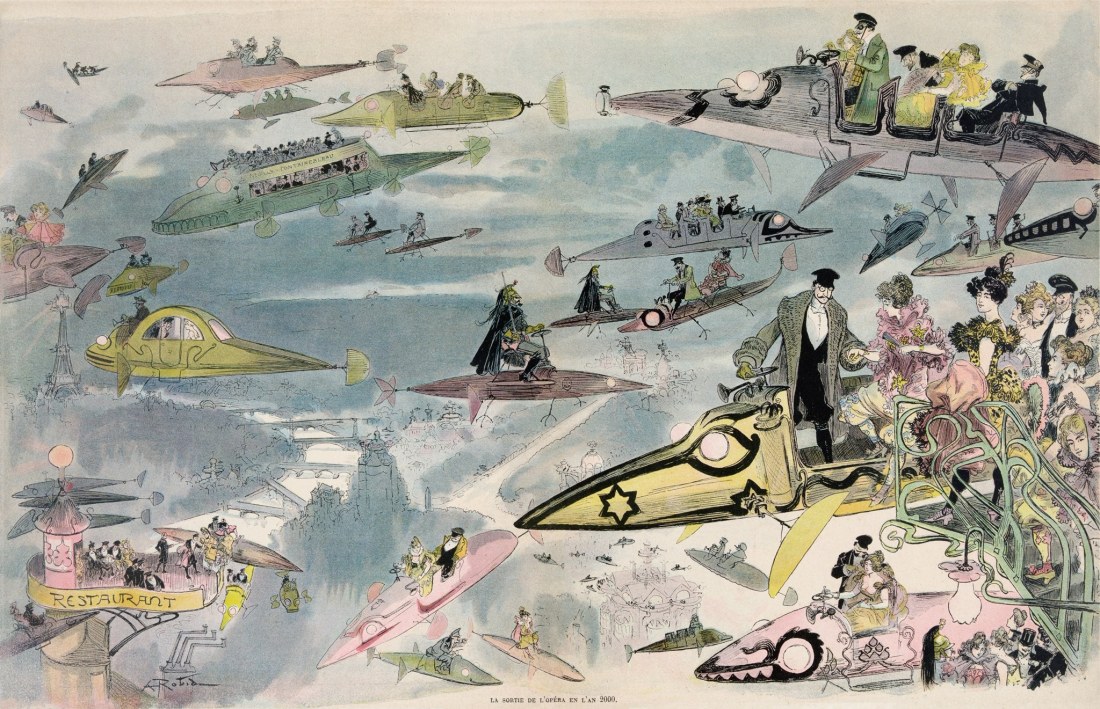

Brian Stableford will be speaking about the evolution of an important early science fiction form, the French roman scientifique, supported by the London Science Fiction Research Community (

Brian Stableford will be speaking about the evolution of an important early science fiction form, the French roman scientifique, supported by the London Science Fiction Research Community ( Mike John Harrison, a veteran of the 60s New Wave SF scene, and Gary Budden, an award-nominated short story writer whose first collection Hollow Shores (Dead Ink Press) is out now, discussed how weird fiction is indispensable for processing contemporary political realities.

Mike John Harrison, a veteran of the 60s New Wave SF scene, and Gary Budden, an award-nominated short story writer whose first collection Hollow Shores (Dead Ink Press) is out now, discussed how weird fiction is indispensable for processing contemporary political realities. Creation of a fictional Doggerland-like continent lay behind one of Mike’s projects for New Worlds, in which elements of a series of seemingly unconnected narratives would reveal that a new continent had appeared. Although the book never came to fruition, the stories evolved and formed part of his new collection, You Should Come With Me Now, published by Comma Press. He read a story from the collection called Psychoarcheology. Ostensibly a satire about the unending discovery of royal remains beneath car parks, it also looked at how the royals themselves are as trapped by their DNA into a life of rule they may not want, as their bodies are trapped beneath tarmac. This layering is an example of one of the different narrative techniques Mike uses to draw the reader through stories that do not have conventional narrative plots. Another is ‘reframing’, in which characters are moved through different landscapes as if on a journey, placing them in unfamiliar locations to accentuate the essential quality of strangeness. The weird, then, is as much to do with the way the story is told as its subject matter.

Creation of a fictional Doggerland-like continent lay behind one of Mike’s projects for New Worlds, in which elements of a series of seemingly unconnected narratives would reveal that a new continent had appeared. Although the book never came to fruition, the stories evolved and formed part of his new collection, You Should Come With Me Now, published by Comma Press. He read a story from the collection called Psychoarcheology. Ostensibly a satire about the unending discovery of royal remains beneath car parks, it also looked at how the royals themselves are as trapped by their DNA into a life of rule they may not want, as their bodies are trapped beneath tarmac. This layering is an example of one of the different narrative techniques Mike uses to draw the reader through stories that do not have conventional narrative plots. Another is ‘reframing’, in which characters are moved through different landscapes as if on a journey, placing them in unfamiliar locations to accentuate the essential quality of strangeness. The weird, then, is as much to do with the way the story is told as its subject matter.

Both novels blend crime fiction and science fiction, challenging the genre boundaries. A Man of Shadows is the film noir-influenced story of a 1940s-style gumshoe private eye searching for a teenage runaway, while The Real-Town Murders follows another private investigator trying to solve a case that seems impossible. The idea for the murder came from Alfred Hitchock, who posited: what if a dead body was discovered in the boot of a car that had been assembled by an automatic factory with no human intervention? Hitch said that if he could work out how the body got there he would make the film. He couldn’t, so never did and now Adam Roberts has picked up the challenge.

Both novels blend crime fiction and science fiction, challenging the genre boundaries. A Man of Shadows is the film noir-influenced story of a 1940s-style gumshoe private eye searching for a teenage runaway, while The Real-Town Murders follows another private investigator trying to solve a case that seems impossible. The idea for the murder came from Alfred Hitchock, who posited: what if a dead body was discovered in the boot of a car that had been assembled by an automatic factory with no human intervention? Hitch said that if he could work out how the body got there he would make the film. He couldn’t, so never did and now Adam Roberts has picked up the challenge.